About Loeb Smith

People

Sectors

Expertise

- Legal Service

- Banking and Finance

- Blockchain, Fintech and Cryptocurrency

- Capital Markets and Privatization

- Corporate

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy

- Insolvency, Restructuring and Corporate Recovery

- Insurance and Reinsurance

- Intellectual Property

- Investment Funds

- Litigation and Dispute Resolution

- Mergers and Acquisitions

- Private Client and Family Office

- Private Equity and Venture Capital

- Governance, Regulatory and Compliance

- Entity Formation and Managed Services

- Consulting

- Legal Service

News and Announcements

Locations

Subscribe Newsletters

Contact

Many thanks to our readers and to our contributing author colleagues for making it possible! Our firm has been ranked as Lexology Legal Influencer for Private client – Central and South America for Q3 2025. This is the third ranking from Lexology this year – here to many more to come 🤜

Thrilled to share that Loeb Smith has won Law Firm of the Year: Client Service at last week’s Hedgeweek® US Awards 2025!

Robert Farrell and Juliette Schembri were present at the event in hashtagNYC to accept the award and celebrate this success. This award reflects our corporate group’s dedication to providing outstanding client service to our clients across the globe every step of the way across their matters. This award inspires us to keep pushing forward, growing stronger, and delivering effective legal advice and solutions to our clients. Global Vision. Client Focus. 🥳 🎉 🥂

Thank you to our clients and colleagues who make this possible and congratulations to all winners and nominees!

Introduction

Among the many investment fund structures provided by the Financial Services Commission (“FSC”) of the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) under the Securities and Investment Business Act (As Revised) of the BVI, Approved Funds and Incubator Funds have for a number of years been very attractive options for Start-up Fund Managers and Emerging Fund Managers. Introduced in 2015 by the BVI’s Securities and Investment Business (Incubator and Approved Funds) Regulations (the “Regulations”), these two open-ended fund structures offer reduced regulatory burden and lower operational costs for Fund Managers to test their investment strategies and abilities. Recognising the inherent limitations of these two fund structures, there are built-in provisions in the Regulations that allow for and facilitate conversion into more robust fund structures (i.e. Private Fund or Professional Fund) upon specific trigger events.

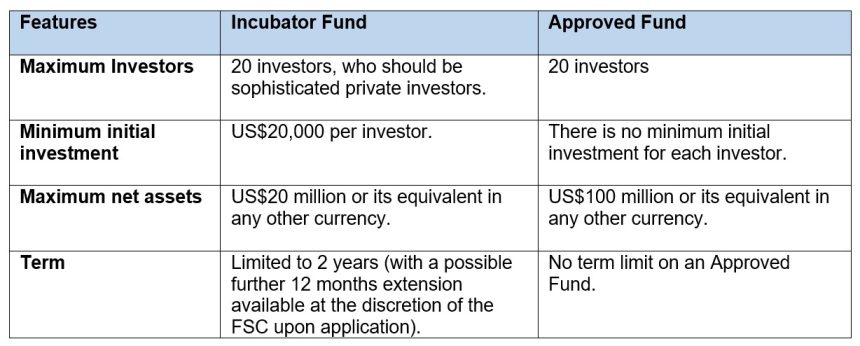

In our previous Legal Briefings, we have discussed in detail the key features and benefits of Incubator Funds and Approved Funds Key Features and Benefits of the BVI Incubator Fund | Loeb Smith, Key Features and Benefits of a BVI Approved Fund | Loeb Smith. As a recap, we set out below the key features of these two categories of BVI funds.

Trigger Events for Conversion

Trigger events are directly linked to the key features of these funds. For an Incubator Fund, the most common triggering event for conversion is the expiration of its Term. At the end of the initial 24 months (“Validity Period”) of the Term, there is a decision to be made in terms of whether the Incubator Fund wishes to terminate its business or continue operation as an investment fund. The other triggering events include (i) the total number of investors close to exceeding 20 and (ii) the net assets exceeding US$20 million over a period of two consecutive months.

For an Approved Fund, as there is no limit on the Term for the Approved Fund, the only triggering events for conversion are the total number of investors exceeding 20 or the net assets exceeding US$100 million over a period of two consecutive months.

When and how to apply for conversion?

Incubator Fund

Upon occurrence of a triggering event, if the Incubator Fund decides to continue its operation as a mutual fund, an application for conversion must be submitted by the Incubator Fund to convert into and be recognised as a Private Fund or a Professional Fund or be approved as an Approved Fund either at least 2 months before the expiry of its Validity Period, or within 7 days after the end of the second month where its number of investors or the net assets exceed the threshold.

In the application, the Incubator Fund should:

-

-

- complete the application form and submit the updated fund documentation for the Fund to be recognised as a Private Fund or a Professional Fund or be approved as an Approved Fund;

- if the Incubator Fund intends to be converted into a Private Fund or a Professional Fund, prepare and submit to the FSC an audit of its (i) current financial position; and (ii) compliance with the requirements of the Regulations. The aforesaid audit should be performed by either a person approved by the FSC under SIBA or pursuant to section 56 of the Regulatory Code, 2009, as an auditor, or a person, if not an approved auditor, who is independent of the Incubator fund and whose normal duties include the performance of such an independent audit function; and

- in case of conversion to a Private Fund or Professional Fund, appoint an auditor, a fund manager, and a custodian pursuant to Mutual Funds Regulations (As Revised) of the BVI (the “MFR”) if it does not have these roles already filled (which in most cases it will not have had filled as they are not compulsory for an Incubator Fund). It may apply for exemption from the custodian or fund manager requirement along with the conversion application.

-

Where an Incubator Fund converts into an Approved Fund, the existing sophisticated private investors in the Incubator Fund shall be treated like any other investor in the Approved Fund.

Where an Incubator Fund converts into a professional fund, the existing investors are grandfathered and do not need to comply with the minimum initial investment amount requirement of US$100,000. This requirement would only apply to new incoming investors.

Approved Fund

Similar to the Incubator Fund, upon a triggering event, if the Approved Fund decides to continue its operation as a mutual fund, an application for conversion must be submitted by the Approved Fund to the FSC to convert into and be recognised as a Private Fund or Professional Fund within 7 days of the end of the second month where its total number of investors or the net assets exceed the threshold.

When filing the application, the Approved Fund should:

-

-

- complete the applicable application form and submit the updated fund documentation for the Fund to the FSC to be recognised as a Private Fund or Professional Fund; and

- appoint the auditor, the fund manager, the fund administrator and the custodian, or apply for applicable exemptions as mentioned above.

-

Different to that for an Incubator Fund, an Approved Fund is not, at the time of applying for conversion, subject to a statutory requirement to submit an audit of its current financial position and compliance with the Regulations.

If the Approved Fund converts into a Professional Fund, each investor is required to demonstrate that it is a professional investor and has a minimum investment amount of US$100,000. There is no exemption for existing investors as in the case of an Incubator Fund.

The Incubator Fund or the Approved Fund should notify all of its investors of the conversion and keep them informed about the proposed change of regulatory status. The FSC may also raise queries about the details of the trigger event and the current circumstances of the Fund.

Options other than conversion

When a trigger event occurs, if the Incubator Fund or Approved Fund decides not to proceed with conversion as discussed above, under the Regulations, it should:

-

-

- commence the process for a voluntary liquidation under the BVI Business Companies Act (As Revised); or

- take necessary steps to amend its constitutional documents to cease to be a Fund and remove all references from its constitutional documents to being an Incubator Fund or Approved Fund (as applicable).

-

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice on the matters covered in this Legal Insight, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of the following:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: robert.farrell@loebsmith.com

E: elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

E: vanisha.harjani@loebsmith.com

E: frost.wu@loebsmith.com

In the absence of any shareholders agreement in place, the rights of the shareholders of a British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) company are governed by the terms of the company’s Memorandum and Articles of Association. However, there can be situations where the majority who control the company act in a way that is prejudicial to the rights of the company’s minority shareholders. In this situation, the BVI courts have jurisdiction to address issues relating to minority shareholder rights and unfair prejudice. One of the most common remedies sought by an aggrieved shareholder is the winding up of the company on just and equitable grounds.

This Legal Briefing will provide an overview of the unfair prejudice regime in the BVI and the remedy of winding up a company on just and equitable grounds. Further, situations where the remedy may or may not apply are also explored in this Legal Briefing.

Unfair prejudice

The BVI Business Companies Act (Revised 2020) (as amended) (“BCA”) provides statutory basis for shareholders to bring an unfair prejudice claim. A shareholder who considers that the company’s affairs “have been, are being or are likely to be, conducted in a manner that is, or any act or acts of the company have been, or are, likely to be oppressive, unfairly discriminatory, or unfairly prejudicial to him or her in that capacity, may apply to the Court for an order”.

In assessing whether the company’s affairs that the aggrieved shareholder has claimed has caused them unfair prejudice, the BVI courts will apply an objective test. Each situation is different. In order to assess whether there is unfair prejudice, the BVI court will consider, amongst other factors:

-

- the company’s constitutional documents (i.e. its Memorandum and Articles of Association);

- the specific facts and circumstances concerning the unfair prejudicial conduct; and

- shareholders’ agreement (if any).

Available remedies

If, on an application by the prejudiced shareholder, the BVI court “considers that it is just and equitable to do so”, it may make any such order as it thinks fit, including, one (or more) of the following:

-

- require the company or any other person to acquire the shares of the aggrieved shareholder or pay them compensation;

- regulate the future conduct of the company’s affairs;

- amend the company’s Memorandum and Articles of Association;

- appoint a receiver of the company;

- appoint a liquidator under the Insolvency Act (Revised 2020) (as amended) (the “Act”);

- direct the rectification of the company’s records; and

- set aside any decision made or action which was taken by the company or its directors which were in breach of the BCA or the company’s constitutional documents.

In light of the above, the BVI court (once satisfied that unfair prejudicial conduct has occurred) have broad discretion as to the relief it can grant in order to address and remedy the prejudice that the shareholder has suffered. Notwithstanding the remedies set out above, in practice, most claimants seek either:

-

- a buy-out of their shares (so as to redeem or withdraw their equity from the company at fair value); or

- the winding up of the company.

BVI court’s winding up jurisdiction – the just and equitable ground

As stated above, one of the most common remedies sought by an oppressed minority shareholder of a BVI company is the court’s just and equitable winding up jurisdiction.

The Act

The court’s jurisdiction to wind up a BVI company on just and equitable grounds is based on statute, namely, the Act. The court’s powers are expressly set out in the Act, which provides that the court may, on the application of a shareholder, appoint a liquidator if it “is of the opinion that it is just and equitable that a liquidator should be appointed”. It should be noted that the court’s power in this respect is circumscribed later in the Act (see below), which provides that where “an application to appoint a liquidator is made by a shareholder…if the Court is of the opinion that—

-

- the applicant is entitled to relief either by the appointment of a liquidator or by some other means; and

- in the absence of any other remedy, it would be just and equitable to appoint a liquidator, it shall appoint a liquidator unless it is also of the opinion that some other remedy is available…and that he or she is acting unreasonably in seeking to have a liquidator appointed instead of pursuing that other remedy.”

Case law

The Act does not contain any guidance as to what exactly constitutes “just and equitable” in relation to applying for an order to appoint a liquidator of the company to wind it up. To that effect, case law authority from the BVI as well as other common law jurisdictions provide useful guidance as to the scope of the court’s power to appoint a liquidator where the court is of the opinion that it is just and equitable to do so. As a starting point, the House of Lords in the English case Ebrahimi v Westbourne Galleries Ltd[1] (“Ebrahimi”) held that the tendency to try to create categories under which the remedy must be brought was wrong – “general words should remain general and not be reduce to the sum of particular instances.”[2]

A similar approach was also taken in the BVI. In Fortune Bright Global Limited v Central Shipping Co., Limited[3], the BVI court stated that the just and equitable basis for the appointment of a liquidator was broad and the foundational principles continue to evolve and be refined[4]. Further, the Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court held in Chu Kong v Lau Wing Yan and Ocean Sino Limited[5] (a case which was later reversed on other grounds on appeal in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council – see below) that the just and equitable ground was a wide one and “must be generously construed to include a wide range of circumstances capable of invoking the court’s jurisdiction.”[6]

Situations where companies have been wound up on just and equitable grounds

It is not possible to provide an exhaustive list of the circumstances where the above equitable principles will apply. The broad equitable principles are to be applied to different cases before the court. The court, when determining whether to make an order, “must itself evaluate the factual matrix in order to form a view as to whether a sufficient reason for making the order is demonstrated”.[7] Notwithstanding this, below is a list of situations which may justify the appointment of a liquidator and the winding up of the company on just and equitable grounds:

Loss of substratum or purpose

A company may be wound up on the just and equitable ground where there has been a loss (or failure) of substratum or objects (e.g., where the company was formed for a certain purpose which has now come to an end, been abandoned or has otherwise become impossible to achieve).

In Re Klimvest PLC[8], the English High Court ordered the winding up of a public listed company on the just and equitable ground for loss of substratum. Judge Cawson KC (sitting as a High Court Judge) held, inter alia:

-

- that whether or not a company can be wound up for failure of substratum is a question of equity between the company and its shareholders; and

- if a company cannot practically pursue its purpose or if the company will not pursue the purpose (or has abandoned it), then a company ought to be wound up as having lost its substratum or purpose.

Judge Cawson KC in Re Klimvest PLC applied Jenkins J’s dictum in the English case of Re Eastern Telegraph Co., Ltd[9] that “if a shareholder has invested his money in the shares of the company on the footing that it is going to carry out some particular object, he cannot be forced against his will by the votes of his fellow shareholders to continue to adventure his money on some quite different project or speculation”.[10]

Where the company is sham

The courts are likely to wind up a company on the just and equitable ground where the company was not formed for a legitimate purpose, but merely with the purpose of extracting money from shareholders and was, from the very beginning a “sham, a bubble, a trap”[11].

Functional deadlock

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (which is the highest court of appeal for BVI cases) in Chu v Lau[12] (on appeal from the BVI courts) recognised that winding-up was a shareholder’s remedy of last resort. Notwithstanding this, the Privy Council stated that a just and equitable winding-up may be ordered if:

-

- there is a functional deadlock, i.e. where an inability of shareholders to co-operate in the management of the company’s affairs has led to an inability of the company to function at board or shareholder level)[13]; and

- the company is a corporate quasi-partnership, a just and equitable winding-up may be justified if there is an irretrievable breakdown in trust and confidence between the shareholders (essentially on the same grounds as would justify the dissolution of a true partnership)[14].

Unauthorised change in the type of business or activity of the company

It should be noted that a breakdown in the relationship between a company’s shareholders is not, in of itself, justification for winding up the company. The Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court in Wang Zhongyong and Others v Union Zone Management Limited and Others[15] stated that for such a situation to escalate to the level of a just and equitable winding up of the company, it must represent or lead to a breach of some underlying agreement (either express or implied) or “some unauthorized change in the type of business or activity for which the company was incorporated in the first place.”[16] In light of this, it would be just and equitable that a company be wound up if it was incorporated for a specific and limited purpose and where the majority shareholders had ignored that purpose.

Lack of probity in the conduct of the company’s affairs

A shareholder does not need to only rely on circumstances which affect them in their capacity as a shareholder in order to bring a claim on the just and equitable ground. The scope is wide for an aggrieved shareholder – they can also rely on any circumstances which affect them in their relations with the company or other shareholders. A company can be wound up on the just and equitable ground if, for example, a lack of probity (in the form of allegations of breaches of fiduciary duty) may constitute the basis of a just and equitable winding up.

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the case of Janet Livingstone Loch and Another v John Blackwood Limited[17] (“Loch”) stated that at the foundation for winding up a company on the just and equitable ground, there must be a justifiable lack of confidence in the conduct and management of the company’s affairs (e.g. because of fraud or serious misconduct by the company). This lack of confidence must be based on the conduct of the company’s directors (and not in respect of the directors’ private life or affairs). Further, such lack of confidence must not be based on the aggrieved shareholder’s dissatisfaction with being outvoted on the company’s business affairs. However, the Loch case further stated that “wherever the lack of confidence is rested on a lack of probity in the conduct of the Company’s affairs, then the former is justified by the latter, and it is under the statute just and equitable that the Company be wound up.”[18]

Failure to pay reasonable dividends

The amount of remuneration for directors, as well as the level of dividend to be declared are, in short, commercial decisions for a company to make (although such decisions must be made in good faith in the company’s best interests as a whole). In the English case of Re a Company (No 00370 of 1987) Ex p. Glossop[19], Harman J. stated that “directors have a duty to consider how much they can properly distribute to shareholders”.[20] If the directors failed to recommend the payment of a dividend to shareholders without due regard to the right of shareholders to have profits distributed to them as far as is commercially possible, the directors’ decision would be open to challenge. It should be noted that the non-payment of dividends in itself does not automatically constitute unfair prejudice. However, where the company can afford to pay reasonable dividends and the directors paid themselves excessive remuneration, the failure to pay dividends can form the basis on a winding up on the just and equitable ground.

Situations where companies have not been wound up on just and equitable grounds

Following on from the above, below is a non-exhaustive list of situations which were not enough to justify winding up a company on the just and equitable basis.

If shareholder is acting unreasonably in failing to pursue alternative remedy

On hearing an application by a shareholder to appoint a liquidator over a company on the just and equitable ground, the court will not appoint a liquidator if there is an alternative remedy and the shareholder is acting unreasonably in failing to pursue that remedy. This is perhaps the most important reason a company would not be wound up even if the shareholder is entitled to the relief. The threshold for bringing a successful unfair prejudice claim is high because winding up a company is a drastic and draconian remedy. Given the high bar, a practical point for the aggrieved shareholder to bear in mind is that they should try and seek a realistic alternative, such as a buyout of their shares by another party. It should be noted that where an offer has been made to buy the shareholder’s shares at fair value and where such offer has been rejected, the shareholder’s unfair prejudice claim may fail if the court concludes that the offer was at fair value because such offer (at fair value) would reflect the remedy that the court is likely to award and so to commence (or continue) such a claim would constitute an abuse of process.

Claim should not be to vindicate personal or business reputation

A claim to wind up a company on just and equitable grounds is not “an appropriate vehicle for the vindication of personal or business reputation, except insofar as that is incidental to the adjudication as to whether the relief sought is justified.”[21]

Breakdown in confidence between shareholders due to “aggrieved” shareholder

In Ebrahimi, it was stated that there would be no winding up if the breakdown in confidence between shareholders was due to the conduct of the “aggrieved” shareholder[22].

Where shareholder’s interest is adverse to those of the company

The court will not grant a winding up order where:

-

- the shareholder seeks to protect interests other than their interests as a shareholder of the company; or

- the application to wind up was not presented as “bona fide” but was made to achieve some collateral purpose (and not to bring about the company’s winding up).

An example of this would be the English case of Re JE Cade & Son Ltd[23]. The petitioning shareholder was the freeholder of land leased to the company which had security of tenure of the land. The court refused to order possession of the land.

Conclusion

The just and equitable ground for winding up a BVI company is a wide, yet powerful remedy for an aggrieved shareholder. The court has broad discretion as to whether to grant such remedy. The winding up of a company that has no chance of continuing would bring finality to the company’s mismanagement and/or misconduct and would appoint independent liquidator(s) in charge to investigate the company’s affairs as well as collect the assets and distribute them.

[1] [1973] AC 360

[2] [1973] AC 360 at [374]

[3] BVIHC (COM) 2015/0036

[4] BVIHC (COM) 2015/0036 at [27]

[5] BVIHCMAP2017/0020

[6] BVIHCMAP2017/0020 at [45]

[7] Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Letten (No 10) [2011] FCA 498 at [14]

[8] [2022] EWHC 596 (Ch)

[9] [1947] 2 All ER 104

[10] [1947] 2 All ER 104 at [109]

[11] Re Neath Harbour Smelting & Rolling Works (1886) 2 TLR 366 at [339]

[12] [2020] UKPC 24

[13] [2020] UKPC 24 at [14]

[14] [2020] UKPC 24 at [15]

[15] BVIHCMAP2013/0024

[16] BVIHCMAP2013/0024 at [53]

[17] [1924] AC 783

[18] [1924] AC 783 at [3]

[19] [1988] 1 WLR 1068

[20] [1988] 1 WLR 1068 at [1076]

[21] Re FI Call Ltd [2015] EWHC 3269 (Ch) at [64]

[22] [1973] AC 360 at [387]

[23] [1991] BCC 360

Further Assistance

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. If you require further advice relating to the matters discussed in this Legal Briefing, please contact us. We would be delighted to assist.

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: robert.farrell@loebsmith.com

E: edmond.fung@loebsmith.com

Background

Litigation can be costly. The potential cost of commencing a claim can often deter a prospective claimant from pursuing a meritorious claim. Third-party litigation funding can solve this dilemma for a prospective claimant by managing the risk and covering the legal costs. The prospective claimant would then be able to focus on commencing and pursuing their claim (rather than have their financial resources used on funding the litigation). This Legal Briefing will explore third-party litigation funding in the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”).

What is third-party litigation funding?

Third-party litigation funding is where a third-party which is not related to the litigation agrees to finance all (or part) of the legal costs of the litigation proceedings. In return, should the claim be successful, the third-party funder receives a financial return from the proceeds which are recovered by the funded party, usually a percentage or a multiple of the capital they have invested in the case. In the event that the claim is unsuccessful, there is normally no obligation on the funded party to repay the funder any capital they have invested (most litigation funding arrangements are provided on a ‘non-recourse’ basis – see below).

There are no specific time limits for a party to obtain third-party litigation funding. However, a party will generally seek funding prior to issuing a claim (but a funder may be prepared to fund the case at a later stage).

It should be noted that the funded party retains control over the case. The third-party funding the litigation may however require updates on the progress of the case (and may withdraw funding if the case subsequently weakens as it progresses).

Third-party litigation funding in the BVI

The historical position

The BVI is a common law jurisdiction and historically, litigation funding was barred in common law jurisdictions (applying the torts of maintenance and champerty). The absence of legislation regulating third-party litigation funding in the BVI has resulted in uncertainty as to whether the common law rules against maintenance and champerty were still in force in the BVI (especially as other common law jurisdictions such as England and Wales began to relax its laws around professional funders in order to facilitate access to justice).

BVI case law in relation to third-party litigation funding is limited. However, two important cases are:

Leremeieva v Estera Corporate Services (BVI) Ltd[1] (“Estera”)

In Estera, Justice Wallbank observed that there was a difference between “mischief” by third-parties being permitted to encourage lawsuits and “the entirely laudable practice of encouraging access to justice for those with good claims who would otherwise be shut-out from the court system. Naturally, a third-party funder cannot be expected to provide funding upon a gratuitous basis. The issue for the court is whether a funding agreement has a tendency to corrupt public justice.”[2] Justice Wallbank further stated that some of the tell-tale signs of a third-party funder improperly seeking to influence the outcome of proceedings include that the funding agreement offering the funder a significant financial advantage conditional upon the proceeding’s outcome, a considerable degree of control over the proceedings and that the funder appears not to be a professional funder or regulated financial institution.

Crumpler v Exential Investments Inc[3] (“Exential”)

Notwithstanding the above, in 2020, the BVI courts had the opportunity to assess and clarify the enforceability of third-party funding arrangements in Exential. The BVI had previously sanctioned litigation funding in other cases but there was no written judgment confirming the court’s power to grant such relief.

The liquidators in Exential had applied for a direction, sanction and/or permission to draw-down on a funding agreement between them, the company and a litigation funder on the grounds that it was in the best interests of the creditors as a whole, did not offend the principles of maintenance and champerty and was a lawful and enforcement agreement under BVI law.

Justice Jack in Exential stated that:

-

- The difficulty the liquidators had was that with such a large number of (comparatively) small creditors, it was difficult to raise the necessary funds to pursue potential avenues of revenue and as a result, the liquidators sought to obtain litigation and liquidation funding.

- The question was whether it was lawful for the liquidators to enter into a funding arrangement whereby the funder would receive a share of the recovery in the litigation. At common law, maintenance and champerty were criminal offences. The Criminal Law Act 1967 had abolished the offences in England and Wales (although the legislation retains the rule of public policy against maintenance and champerty). Section 328 of the BVI’s Criminal Code 1997 abolished the common law offences of maintenance and champerty.

- The approach adopted in England and Wales which permitted third-party litigation funding at common law was adopted by other jurisdictions such as Bermuda, Australia and the Cayman Islands.

- The funding arrangement proposed in Exential was not contrary to BVI public policy – indeed, it was the contrary. Without funding, the liquidators would be unable to recover assets for the benefit of the company’s creditors. Approving the funding arrangement was essential to ensure access to justice.

What types of costs may be funded by third-party?

A third-party litigation funder will usually fund legal fees and disbursements such as investigatory costs or expert’s costs. They may insist (as a condition of any funding) that the funded party obtain after the event (ATE) insurance to cover the risks of adverse costs.

What are the key benefits of third-party litigation funding?

It is clear that third-party litigation funding offers several key benefits to the funded party. Some of these include:

-

- promoting access to justice by enabling the funded party to pursue a meritorious claim which otherwise may not have been financially viable;

- freeing up the funded party’s capital and not diverting funds away from them (in the form of upfront legal costs) – which can assist the funded party with cash flow preservation;

- mitigating litigation risk for the funded party; and

- the funded party only repays the funder if they are successful in the litigation. There is generally no repayment by the funded party if the claim is not successful. This ‘non-recourse’ financing reduces the financial risks faced by the funded party.

Conclusion

There are no longer any statutory restrictions in the BVI on third-party litigation funding. The court in Exential approved a third-party funding agreement between the liquidators and the third-party litigation funder. Given these developments in recent years, the third-party litigation funding market in the BVI is expanding and so a variety of funding options is now likely to be available. Even though such funding arrangements are now permissible as a matter of BVI law, there would appear to still be a need to prevent a third-party from encouraging a claim where there is little or no grounds for bringing such claim. With this in mind, third-party litigation funding must be responsible and the principles set out in the case law above should be adhered to.

[1] BVIHC (COM) 81 of 2020

[2] BVIHCM2017/0118 at [153]

[3] BVIHCM2017/0118

Further Assistance

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. If you require further advice relating to the matters discussed in this Legal Briefing, please contact us. We would be delighted to assist.

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: robert.farrell@loebsmith.com

E: edmond.fung@loebsmith.com

In the prevailing economic conditions investors in offshore companies registered in the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) are increasingly being forced to consider their rights against directors who may have been responsible for mismanagement of the company’s affairs. Minority shareholders, in particular, are keen to understand the availability of remedies which allow them to overcome “wrongdoer control.” That is to say, the common situation where the composition and direction of the board is controlled by majority shareholders. We have set out below a brief summary of the duties owed by directors and the remedies available to shareholders in each of these two jurisdictions.

What is scope of director’s duties?

Cayman Islands

The duties of a director of a Cayman company are found in the common law and include the duty to act bona fide in the best interests of the company, a duty not to exercise his or her powers for purposes for which they were not conferred and not to make secret profits.

BVI

The law governing the duties of directors and conflicts is set out in the BVI Business Companies Act (as revised) (the “Act”). These largely mirror the position at common law and include, for example:

-

- the duty to “act honestly and in good faith and in what the director believes to be in the best interests of the company”;

- the duty to exercise powers “for a proper purpose” and a requirement that a director “shall not act, or agree to the company acting, in a manner which contravenes this Act or the memorandum or articles of the company”; and

- a requirement that a director “shall, forthwith after becoming aware of the fact that he or she is interested in a transaction entered into or to be entered into by the company, disclose the interest to the board of the company.”

It is interesting to note that the Act provides that a director of a company that is a wholly-owned subsidiary, subsidiary or joint venture company may, subject to certain requirements, act in the best interests of the relevant parent, or in the case of the joint venture company, the relevant shareholders even though such act may not be in the best interests of the company of which they are a director.

What are the standard director’s duties?

Cayman Islands

While the decisions of English common law cases are not binding in the Cayman Islands, they are persuasive authority. Accordingly, a large body of the English caselaw authority on a director’s duties has been followed by the Cayman Islands court and applies to the Cayman Islands such that a director is under a duty to act with reasonable care, skill and diligence in the performance of his or her duties. In the English authority of Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co [1925] Ch. 407 it was held that “a director need not exhibit in the performance of his duties a greater degree of skill than may reasonably be expected from a person of his knowledge and experience. This highly subjective test, however, has been met with increasing criticism in more recent years and there is further English caselaw authority to suggest that directors are nevertheless subject to an objective duty to “take such care as an ordinary man might be expected to take on his own behalf” (Dorchester Finance Co v Stebbing [1989] BCLC 498 (decided in 1977)). As such, a distinction appears to be drawn between the duty of skill on the one hand and the duty to take care on the other. However, in Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co it was further held that “in respect of all duties that, having regard to the exigencies of business, and the articles of association, may be properly left to some other official, a director is, in the absence of grounds for suspicion, justified in trusting to that official to perform such duties honestly.”

BVI

In terms of the standard of care that directors of BVI companies must show, the Act provides that a director “when exercising powers or performing duties as a director, shall exercise the care, diligence, and skill that a reasonable director would exercise in the same circumstances taking into account, but without limitation-

-

- the nature of the company;

- the nature of the decision; and

- the position of the director and the nature of the responsibilities undertaken by him or her.”

This duty is qualified in the Act to the extent that the director of a company is entitled to rely upon the books, records and financial statements of the company in question and/or employees and professional advisers provided that in doing so he or she acts in good faith, undertakes a proper inquiry where this is warranted and has no knowledge of a reason for not placing reliance on the said documents.

What are the key remedies available to a member or shareholder?

Cayman Islands

The following remedies are available to a member of a Cayman company:

-

- A personal action against the company (where the company has breached a duty which is owed to the member personally);

- A representative action (similar to a personal action such a claim would lie for breach of a duty owed to a group of shareholders);

- A derivative, or multiple derivative claim (this is the most common type of action. See below); or

- A petition to wind up the company on just and equitable grounds. (This is seen as a last resort because it risks placing the company into liquidation although the Cayman Companies Act (As Revised) (the “Companies Act”) provides the Court with the option of making an alternative order. See below).

BVI

The members of a BVI company may pursue the following remedies:

-

- A personal action (on the same grounds as at common law in the Cayman Islands);

- A representative action which provides that the Court may appoint a member “to represent all or some of the members having the same interest and may, for that purpose, make such order as it thinks fit”. An order would include an order “as to the control and conduct of the proceedings” and “directing the distribution of any amount ordered to be paid by a defendant in the proceedings among the members represented.”;

- A derivative claim; or

- An unfair prejudice claim.

The most common type of remedies sought by minority shareholders are derivative claims and unfair prejudice claims (see below).

What are derivative claims and what is their legal basis?

Cayman Islands

A derivative action is a claim commenced by one or more minority shareholders on behalf of a company of which they are a member in respect of loss or damage which that company has suffered. Such a claim can only be brought in certain circumstances and amounts to an exception to the rule that a company, as a separate legal person, should sue and be sued in its own name (often referred to as the rule in the English authority of Foss v Harbottle (1843) 2 Hare 461; 67 E.R 189). In the Cayman Islands the law governing derivative actions is drawn from the common law rather than statute.

BVI

While the English common law applies in the BVI, members’ remedies have been given a statutory footing in the Act (see below).

What is the procedure for commencing a derivative action?

Cayman Islands

As with the majority of actions commenced in the Cayman Islands, derivative claims are normally begun by serving a writ and statement of claim on the relevant defendant or defendants. Grand Court Rules O.15, r. 12A provides that where the defendant gives notice of an intention to defend the claim then the plaintiff must apply to the court for leave to continue the action. Such an application should be supported by affidavit evidence verifying the facts on which the claim and entitlement to sue on behalf of the company are based. Pursuant to Grand Court Rules O.15 r.12A(8) on the hearing of the application, the court may grant leave to continue the action for such period and upon such terms as it thinks fit, dismiss the action, or adjourn the application and give such direction as to joinder of parties, the filing of further evidence, discovery, cross-examination of deponents and otherwise as it considers expedient. In Renova Resources Private Equity Limited v Gilbertson and Others [2009] CILR 268, Foster., J affirmed the application in the Cayman Islands of the test to be applied in determining whether to grant leave to continue the action put forward by the English Court of Appeal in Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd (No.2) [1981] Ch 257. Foster, J., held that: “(…) there are two elements to this: first the plaintiff [is] required to show prima facie that there [is] a viable cause of action vested in the company and, secondly, that the alleged wrongdoers [have] control of the company (or could block any resolution of the company or the board) and thereby prevent the company bringing an action against themselves.”

BVI

The Act provides that subject to certain exceptions, “the Court may, on the application of a member of a company, grant leave to that member to-

-

- bring proceedings in the name and on behalf of that company; or

- intervene in proceedings to which the company is a party for the purpose of continuing, defending or discontinuing the proceedings on behalf of the company.”

Without limiting the above, in determining whether to grant leave, “the Court must take the following matters into account-

-

- whether the member is acting in good faith;

- whether the derivative action is in the interests of the company taking account of the views of the company’s directors on commercial matters;

- whether the proceedings are likely to succeed;

- the costs of the proceedings in relation to the relief likely to be obtained; and

- whether an alternative remedy to the derivative claim is available.”

It should be noted that leave to bring or intervene in proceedings may be granted “only if the Court is satisfied that-

-

- the company does not intend to bring, diligently continue or defend, or discontinue the proceedings, as the case may be; or

- it is in the interests of the company that the conduct of the proceedings should not be left to the directors or to the determination of the shareholders or members as a whole.”

Is it possible to bring multiple derivative claims (“MDCs”)?

Cayman Islands

In Renova the Grand Court held that in appropriate circumstances MDCs would be permitted. In that case, the plaintiff had brought an action in respect of loss incurred by a wholly-owned subsidiary of the company in which it was a shareholder and therefore loss to the subsidiary caused indirect loss to its parent company and shareholders. However, the rule against the recovery of reflexive loss applied such that a shareholder or parent company would not be permitted to claim for indirect losses which mirrored those losses suffered directly by the relevant subsidiary or indeed sub-subsidiary on whose behalf action was being brought.

BVI

In Microsoft Corporation v Vadem Ltd[1] the Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court held that BVI law which has been codified in this area “does not permit double derivative proceedings.” That said, English caselaw authority such as Universal Project Management Services Ltd v Fort Gilkicker Ltd[2] may open up arguments that such actions are nevertheless available in the jurisdiction at common law.

What remedies are available for unfair prejudice and what is their legal basis?

Cayman Islands

Pursuant to the Companies Act the court may wind up a company if it is of the opinion that it would be just and equitable for it to do so. The Companies Act provides that where such a petition is presented by members of the company as contributories on the ground that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up, the Court shall have jurisdiction to make the following orders, as an alternative to a winding-up order, namely:

-

- an order regulating the conduct of the company’s affairs in the future;

- an order requiring the company to refrain from doing or continuing an act complained of by the petitioner or to do an act which the petitioner has complained it has omitted to do;

- an order authorising civil proceedings to be brought in the name of and on behalf of the company by the petitioner on such terms as the Court may direct; or

- an order providing for the purchase of the shares of any members of the company by other members or by the company itself and, in the case of a purchase by the company itself, a reduction of the company’s capital accordingly.

BVI

The Act provides that a member “who considers that the affairs of the company have been, are being or are likely to be, conducted in a manner that is, or any act or acts of the company have been, or are, likely to be oppressive, unfairly discriminatory, or unfairly prejudicial to him or her in that capacity, may apply to the Court for an order”. If on an application “the Court considers it just and equitable to do so, it may make such order as it thinks fit, including, without limiting the generality of this subsection, one or more of the following orders:

-

- in the case of a shareholder, requiring the company or any other person to acquire the shareholder’s shares;

- requiring the company or any other person to pay compensation to the member;

- regulating the future conduct of the company’s affairs;

- amending the memorandum and articles of the company;

- appointing a receiver of the company;

- appointing a liquidator of the company;

- directing the rectification of the records of the company; and

- setting aside any decision made or action taken by the company or its directors in breach of this Act or the memorandum or articles of the company.”

Further Assistance

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice on the matters covered in this Legal Briefing, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of the following:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: robert.farrell@loebsmith.com

E: edmond.fung@loebsmith.com

Introduction

In the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”), there are three main ways that a company can restructure or reorganize.

These are:

-

- a Plan of Arrangement – governed by the BVI Business Companies Act, 2004 (as revised) (“BCA”);

- a Scheme of Arrangement – governed by the BCA; and

- a Company Creditors’ Arrangement (“CCA”) – governed by the Insolvency Act, 2003 (as revised) (“Insolvency Act”) as this is a debt-related procedure.

It should be noted that a Plan of Arrangement and a Scheme of Arrangement focuses on restructuring equity. On the other hand, a Creditors’ Arrangement is available for restructuring debt. This Legal Insight will explore these three procedures.

Plan of Arrangement

A BVI Plan of Arrangement is used for significant corporate restructurings, such as mergers, asset sales, re-organisation, reconstructions, and the dissolution of a company. It offers a flexible, court-supervised method to implement complex transactions, providing greater certainty and protection for directors and stakeholders compared to purely private corporate restructurings.

A Plan of Arrangement is commenced by a company’s directors. Alternatively, if a company is in voluntary liquidation, it will be initiated by the voluntary liquidator. The company need not be insolvent before a Plan of Arrangement can be considered.

The BCA defines an “arrangement” and the definition includes a reorganisation or restructuring of a company. The company’s directors need to consider whether a Plan of Arrangement is in the company’s best interests, or its creditors or its members. A Plan of Arrangement may permit a company to, among other things, reorganise, merge, consolidate or separate its businesses as well as dissolve the company.

The directors will need to approve the Plan of Arrangement. Once they have, the company must make an application to the BVI court to approve the proposed arrangement. The court has the power to approve, amend or reject the proposed Plan of Arrangement which is the subject of the application. The court will also determine (i) to whom notice of the proposed Plan of Arrangement is to be given, (ii) whether the approval by any person should be obtained and the manner of obtaining the approval, and (iii) whether to conduct a hearing and permit any interested person to appear.

Further, the court will also determine whether any holder of shares, debt obligations or securities in the company may dissent to the proposal – if so, any dissenting party may receive payment of fair value in respect of their shares, debt obligations or other securities. It should be noted that the BCA provides for the right of dissenters (unlike the Scheme of Arrangement provisions).

In the event that the court confirms the proposed Plan of Arrangement, the directors must give notice to and (if required) seek approval from the relevant persons. Once the Plan of Arrangement is approved by those persons, the directors will, on behalf of the company, execute the articles of arrangement which shall contain:

-

- the Plan of Arrangement;

- a copy of the court order which approved the Plan of Arrangement; and

- information of how the Plan of Arrangement was approved.

The executed articles of arrangement are then required to be filed with the Registrar of Corporate Affairs (“Registrar”) who shall register them. Once registered, the company will be issued with a certificate. The effective date of a Plan of Arrangement is the date that the articles of arrangement are registered by the Registrar (or on such date subsequent thereto, not exceeding 30 days, as is stated in the articles of arrangement).

Scheme of Arrangement

In the BVI, Schemes of Arrangement are used for corporate restructuring and transactions like takeovers, allowing companies to achieve a court-sanctioned compromise with their creditors or members. They are typically used to bind all affected parties to the arrangement, provide greater certainty than private transactions, facilitate exemptions from other laws (like the US Securities Act), and manage complex restructurings, including demergers or consolidations.

A Scheme of Arrangement under the BCA is a statutory mechanism which enables a company to enter into a compromise or arrangement with its creditors, or its members. Similar to the Plan of Arrangement, there is no requirement that the company be insolvent when the application to the court is made.

An application for a Scheme of Arrangement can be commenced by (i) the company, (ii) a creditor, (iii) a member, (iv) if the company is in administration within the meaning of the Insolvency Act, by the administrator, or (v) a liquidator (either a voluntary liquidator or one appointed under the Insolvency Act) by applying to the court for a meeting of creditors or members.

A meeting will be convened, and the Scheme of Arrangement will be voted on. The Scheme of Arrangement will be approved if a majority in number representing at least 75% in value of the creditors (or class of creditors) or members (or class of members), as the case may be, present and voting either in person or by proxy at the meeting agree to the compromise or arrangement. If approved, the applicant must then return to the court for the court to sanction the Scheme of Arrangement, and, if sanctioned by the court, is binding on all the creditors or class of creditors, or the members or class of members, as the case may be, and also on the company or, in the case of a company in voluntary liquidation or in liquidation under the Insolvency Act, on the liquidator and on every person liable to contribute to the assets of the company in the event of its liquidation.

The Scheme of Arrangement will only be binding on all creditors, members, the company, and (where applicable) a liquidator once the court order (which sanctioned the Scheme of Arrangement) has been filed with Registrar. A copy of the court order shall be annexed to every copy of the company’s memorandum of association issued after the order has been made.

Company Creditors’ Arrangement

In the BVI, a CCA is typically used when a company is insolvent or likely to become insolvent and needs to restructure its debts with the approval of its creditors to avoid liquidation. The process is initiated by the directors or a liquidator and supervised by a BVI-licensed insolvency practitioner, with the aim of implementing a debt-restructuring plan that, if approved by 75% in value of the creditors, becomes binding on all creditors.

A CCA is a compromise between a company and its creditors which enables the parties to vary the rights of the creditors and to cancel the liability of a debtor (in whole or in part).

The directors of the company initiate the process by proposing an arrangement and nominating an interim supervisor to act. The board of directors can commence this procedure if it believes on reasonable grounds that the company is insolvent or is likely to become insolvent. If the company is already in liquidation, the liquidator can make the proposal.

The directors must pass a resolution:

-

- stating that the company is insolvent or is likely to become insolvent;

- approving a written proposal which explains how the creditors’ rights will be varied or cancelled; and

- nominating an eligible insolvency practitioner to be appointed interim supervisor.

Unless the secured creditors agree in writing to the contrary, a CCA will not affect a secured creditor’s right to enforce its security interest or vary the liability secured by the security interest. It is the same in relation to preferred creditors. It should be noted that unless agreed in writing, a preferred creditor will not receive less than it would have received in a liquidation had the company liquidation commenced on the same date as the CCA.

The proposal must be approved by 75% of the creditors (calculated by reference to the value of the debt rather than on a poll vote basis). If the proposal is approved by 75% of the creditors in value, the supervisor will be appointed. The CCA will be binding on the company, each member and each creditor. The supervisor will immediately take possession of the company’s assets. It should be noted that the directors (or the liquidator, if applicable) will remain in control of the company. The supervisor’s main function is to ensure that the CCA terms are implemented. After the approval of an arrangement, the board (or the liquidator, if applicable), shall forthwith take all necessary steps to put the supervisor into possession of the assets included in the arrangement.

It should be noted that there is no statutory time period within which a CCA must be completed. To date, CCAs are not popular in the BVI. A reason for this is perhaps because the supervision aspect discourages a company from considering this option and opting for a Scheme of Arrangement instead. Further, given that the BVI is a creditor friendly jurisdiction, it is common for a creditor to serve a statutory demand and apply for the appointment of a liquidator as the procedure set out in the Insolvency Act is fairly straightforward.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice on the matters covered in this Legal Insight, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of the following:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: robert.farrell@loebsmith.com

E: elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

E: vanisha.harjani@loebsmith.com

E: edmond.fung@loebsmith.com

British Virgin Islands on FATF Grey List – Navigating the New Compliance Requirements, discussion topics: 1. Increased risk of fines for non-compliance; 2. AML – increase in on-site inspection of regulated entities and AML audits; 3. Beneficial ownership; and 4. Economic substance.

Share

Speaker

Introduction

The registration of beneficial ownership information in respect of British Virgin Islands (the “BVI”) companies and the potential for that information to be disclosed subsequently has long been the subject of speculation and understandable concern by owners of companies and other relevant entities in the BVI.

Political pressure from the Governments of several nations (including that of Great Britain, of which the BVI is an “overseas territory”) as well as the ever increasing efforts of organisations such as the Financial Action Task Force, contributed to a general sense that the ultimate end destination for BVI companies would be a fully transparent and publicly accessible beneficial ownership database, much like the one that is available via Companies House in respect of all companies incorporated in the United Kingdom.

However, judgments handed down by the European Court of Justice (the “ECJ”) in July 2022 in the cases of La Quadrature du Net v. Conseil d’État[1] and La Quadrature du Net and Others v. Conseil d’État[2] have proven to be instrumental in preventing, or in the very least postponing indefinitely, the march towards complete transparency of beneficial ownership in the BVI.

In these judgments, the ECJ held that unrestricted public access to beneficial ownership information is not permitted on the basis that it would breach rights to privacy and data protection and that instead a “legitimate interest” must first be demonstrated by those who are seeking access to beneficial ownership information. The ECJ considered that this approach would strike the right balance between preserving privacy and continuing the fight against money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing.

Beneficial ownership filings in the BVI

Under the Beneficial Ownership Secure Search System Act, (Revised 2020) which was first enacted in June 2017 (the “BOSS Act”), the BVI adopted a conservative approach to the collection and monitoring of beneficial ownership information. All information uploaded to the platform was tightly controlled with access only being granted for official purposes to regulators, international tax authorities and other international governmental and quasi-governmental agencies and authorities.

Under the Beneficial Ownership Secure Search System Act, (Revised 2020) which was first enacted in June 2017 (the “BOSS Act”), the BVI adopted a conservative approach to the collection and monitoring of beneficial ownership information. All information uploaded to the platform was tightly controlled with access only being granted for official purposes to regulators, international tax authorities and other international governmental and quasi-governmental agencies and authorities.

Whilst reform seemed inevitable for the reasons given above, the rulings of the ECJ in the above-mentioned cases led to an announcement in December 2023 that the BVI would, broadly speaking, follow the approach approved by the ECJ whereby beneficial ownership information would only be disclosed to those with a ‘legitimate interest’ in receiving it. This approach has now been enacted in the BVI Business Companies and Limited Partnerships (Beneficial Ownership) Regulations 2024 (as revised) (the “Regulations”).

What information regarding beneficial ownership must be filed in the BVI?

Under the Regulations and subject to the exemptions described below, beneficial ownership details for all BVI Business Companies and BVI registered limited partnerships must be disclosed via upload to the ‘VIRGGIN’ database. This applies to beneficial owners who beneficially own 10% or more of the entity in question. The beneficial ownership information that must be disclosed is:

-

- the full legal name, nationality and date of birth of each beneficial owner per their official document (e.g. government issued photo identification);

- the current residential address of each beneficial owner;

- the nature of each beneficial owner’s ownership or control (e.g. voting rights, direct / indirect ownership and/or the ability to appoint and remove directors); and

- the date on which they became a beneficial owner, within the meaning of the Regulations.

Notwithstanding the general requirement to disclose beneficial ownership, there are exemptions available which means beneficial ownership information need not be supplied. For example, the requirement to disclose beneficial ownership information under the Regulations does not apply to:

-

- entities whose shares are listed on a recognised stock exchange (a “Listed Entity”);

- entities who are themselves a subsidiary of a Listed Entity;

- BVI entities who are regulated under alternative regimes and whose beneficial ownership information is separately monitored, such as investment funds (whether regulated in the BVI or elsewhere) or a subsidiary of such an investment fund; and

- an entity in which the Government of the BVI (or other recognised international government) owns a majority stake.

Disclosure of filed beneficial ownership information – ‘legitimate interest’

Those who have a ‘legitimate interest’ may submit a request to access beneficial ownership information pursuant to the Policy on Rights of Access to the Register of Beneficial Ownership for BVI Business Companies and Limited Partnerships (the “Policy”). The applicable fee for single access to beneficial ownership information is US$75 which will not be refunded even if the application is refused.

The Policy defines a ‘legitimate interest’ as a “demonstrable and bona fide interest in accessing beneficial ownership information” for one of the following purposes:

-

- in connection with the investigation, prevention or detection of suspected activity involving money laundering, terrorist financing and/or proliferation financing;

- conducting customer due diligence obligations in the context of certain types of entity; and

- where the legal entity concerned is connected with a person who has been convicted of, or is the subject of criminal proceedings for, an offence involving money laundering, terrorist financing or proliferation financing,

provided that access under this regime is limited to persons who (whether directly or indirectly), hold an interest of 25% or more in the relevant BVI entity (i.e. disclosure will not be made in respect of persons holding an interest of less than 25% in the relevant entity, regardless of any legitimate interest).

Upon receipt of a request for ‘legitimate access’, the Registrar will process the application within 12 business days of receipt. If the Registrar determines that the application for legitimate access meets the requirements of the Policy and the Regulations, the Registrar will notify the entity that is the subject of the request (the “Subject Entity”). This notification will include:

-

- where the person submitting the request is an individual, the purpose of the request only; and

- where the person submitting the request is not an individual, the name of the requesting person and the stated purpose of the request.

The Subject Entity will then have a period of five business days within which to object to the disclosure of its beneficial ownership information. To file such an objection, the Subject Entity must give reasons for the objection which may include:

-

- a reasonable belief that disclosure would expose a beneficial owner to disproportionate or other serious risks such as persecution, fraud, kidnapping, blackmail, extortion, harassment, violence or other intimidation;

- a statement confirming that the beneficial ownership information relates to a minor or other person lacking legal capacity;

- a statement confirming that disclosure of beneficial information will or is likely to raise issues of national security (whether in the BVI or elsewhere); and/or

- a statement that the request is of a nature that the Registrar should form the view that disclosure of the beneficial information is not in the public interest.

Supporting evidence should also be provided which justifies the objection that is raised. If the objection is upheld, the requester will be notified of the decision and of their right to appeal. If the objection is not considered to be justified, the Registrar will grant access to the information and the Subject Entity will be informed of its right to appeal. If such an appeal is lodged, beneficial information will not be disclosed pending the outcome of that appeal.

In circumstances where no objection is raised, the beneficial information will be disclosed to the requester.

The above stated grounds (risk of harm, beneficial ownership information relating to a minor or person lacking legal capacity, issues of national security and disclosure not being in the public interest) may also be used to make an application to the Registrar for exemption from disclosure of beneficial information. Supporting evidence must be provided with this type of application also and the Registrar will generally make a decision within 12 business days of receipt of the application.

Conclusion

The Regulations and the Policy appear to be well structured and well considered. The Regulations (supported by the Policy) strive to strike the right balance between permitting disclosure where it is legitimate and proportionate in order to continue the fight against, money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing whilst also protecting those who might be placed at risk if disclosure is permitted. The Regulations and the Policy do not adopt the UK model where all such information is publicly available, but instead follows the broad approach that has been approved by the ECJ and, by doing so, the BVI has aligned itself with international best practice on beneficial ownership transparency, providing competent authorities with access to necessary information while maintaining robust safeguards. This measured approach demonstrates a pragmatic balance between transparency, regulatory effectiveness, and the protection of legitimate privacy interests, positioning the BVI as a jurisdiction that is both compliant with global standards and sensitive to the operational realities of its businesses and residents.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice on the matters covered in this Legal Insight, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of the following:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: robert.farrell@loebsmith.com

E: elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

E: vanisha.harjani@loebsmith.com

E: vivian.huang@loebsmith.com

E: faye.huang@loebsmith.com

We’re proud to be shortlisted at this year’s Private Equity Wire® US Awards 2025 in the following categories:

- Law Firm of the Year: Client Services Award

- Law Firm of the Year: Transactions Award

- Law Firm of the Year: Fund Structuring Award

- Law Firm of the Year: Overall Award

Please support the fantastic work of our Cayman Corporate/Funds Group by voting @LoebSmithAttorneys by Friday 5 September on this link: https://pew-awards.evalato.com/public-evaluation/19227/login