About Loeb Smith

People

Sectors

Expertise

- Legal Service

- Banking and Finance

- Blockchain, Fintech and Cryptocurrency

- Capital Markets and Privatization

- Corporate

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy

- Insolvency, Restructuring and Corporate Recovery

- Insurance and Reinsurance

- Intellectual Property

- Investment Funds

- Litigation and Dispute Resolution

- Mergers and Acquisitions

- Private Client and Family Office

- Private Equity and Venture Capital

- Governance, Regulatory and Compliance

- Entity Formation and Managed Services

- Consulting

- Legal Service

News and Announcements

Locations

Subscribe Newsletters

Contact

Introduction

What changes have been introduced recently in Cayman Islands law that you believe will enhance the jurisdiction’s offering in the investment funds industry?

In June 2016 the Cayman Islands brought into effect The Limited Liability Companies Law, 2016 (the “LLC Law”) which introduces a new Cayman Islands limited liability company (an “LLC”). Since July 2016 there has been an increasing number of LLCs formed and also a large number that have transferred to the Cayman Islands by way of continuation from other jurisdictions. The Cayman Islands LLC structure will be attractive for general partner entities and other carried interest distribution vehicles because while the LLC has the benefit of being (like a Cayman Islands exempted company) a separate corporate entity with limited liability, it does not have the maintenance of capital restrictions applicable to exempted companies and therefore has more flexibility to make distributions of income and capital through the terms of the LLC Agreement. For the same reason, LLCs are also proving attractive for management company entities. We expect that over the next few years LLCs might also prove attractive as a structure for offshore funds in order to align the rights of investors between onshore and offshore investment funds in master/feeder structures.

What are the key features of a Cayman LLC?

The key features are:

An LLC formed under the LLC Law is similar in structure to the Delaware LLC as the LLC Law is broadly based on the Limited Liability Company Act in the State of Delaware. However the LLC Law has also preserved the broad legal principles applicable to Cayman Islands companies and the rules of equity and common law.

An LLC is a corporate entity which has separate legal personality to its members.

Formation of an LLC is straightforward. It requires the filing of a registration statement with the Companies Registry and payment of the requisite Government fee.

An LLC must have at least one member. It can be member managed (by some or all of its members) or the LLC agreement can provide for the appointment of persons (who need not be members) to manage and operate the LLC.

The liability of an LLC’s members is limited. Members can have capital accounts and can agree amongst themselves (in the LLC agreement) how the profits and losses of the LLC are to be allocated and how and when distributions are to be made (similar to a Cayman Islands exempted limited partnership)

An LLC may be formed for any lawful business, purpose or activity and it has full power to carry on its business or affairs unless its LLC agreement provides otherwise.

The following statutory registers are required to be maintained for an LLC but, similarly to the requirement for a Cayman Islands exempted company, only an LLC’s register of managers is required to be filed with the Companies Registry:

a register of members;

a register of managers; and

a register of mortgages and charges.

The register of managers and register of mortgages and charges are required to be maintained in a manner similar to the register of directors and register of mortgages and charges for a Cayman Islands exempted company.

Subject to any express provisions of an LLC agreement to the contrary, a manager of the LLC will not owe any duty (fiduciary or otherwise) to the LLC or any member or other person in respect of the LLC other than a duty to act in good faith in respect of the rights, authorities or obligations which are exercised or performed or to which such manager is subject in connection with the management of the LLC provided that such duty of good faith may be expanded or restricted by the express provisions of the LLC agreement.

The Segregated Portfolio Company (“SPC”) is increasingly being used as a structure for investment funds, what do think explains this increasing popularity?

Under the Cayman Islands Companies Law (the “Companies Law”), an SPC is an exempted company which has been registered as a segregated portfolio company. It has full capacity to undertake any object or purpose subject to any restrictions imposed on the SPC in its Memorandum of Association. The Memorandum of Association of an SPC usually gives the SPC full capacity to pursue very broad objects. Once registered under the Companies Law, an SPC can operate segregated portfolios (“SPs”) with the benefit of statutory segregation of assets and liabilities between portfolios.

The appeal of SPCs extends beyond investment funds and the structure is often used in capital markets and securitisation transactions. In the investment funds context, SPCs greatly enhance the versatility and efficiency of Cayman Islands fund structures. It allows investors to access different trading strategies or investments, different markets or different managers through a single corporate vehicle whilst simultaneously providing the segregation of assets and liabilities through each SP (unlike, for example, a ‘multi class’ fund where there is typically a single legal entity offering various classes of shares designated according to the designated portfolio investment) and avoiding cross class liability issues which could arise with ‘multi class’ funds.

The Companies Law permits an SPC to create one or more SPs in order to segregate the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within one SP from the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within another SP of the SPC. The general assets and general liabilities of the SPC (i.e. assets and liabilities which cannot be properly attributed to a particular SP) are held within a separate general account rather than in any of the SP accounts. Each SP should have, as appropriate, its own bank account, brokerage account, and other accounts to hold its assets to avoid co-mingling with the assets of other SPs.

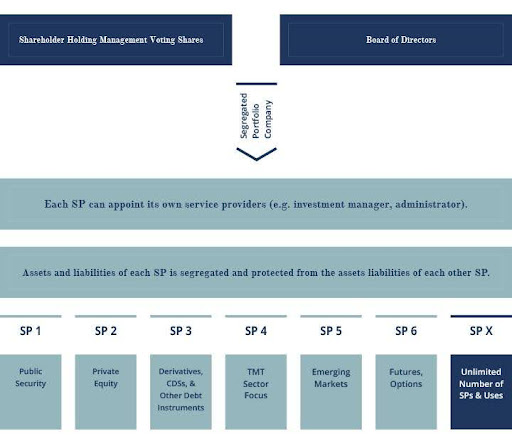

Figure 1. An unlimited number of SPs can be created by the SPC to hold various assets, employ different investment strategies or have varying sector focus.

The Companies Law requires that segregated portfolio assets must only be available and used to meet liabilities to the creditors of the SPC who are creditors in respect of that SP and who are thereby entitled to have recourse to the segregated portfolio assets attributable to that SP for such purposes. Segregated portfolio assets should not be available or used to meet liabilities to, and must be absolutely protected from, the creditors of the SPC who are not creditors in respect of that SP, and who accordingly are not entitled to have recourse to the segregated portfolio assets attributable to that SP.

Accordingly, a creditor will only have recourse to assets from SPs with which it has contracted and creditors will have no recourse to the assets of other SPs of the SPC which are protected under the Companies Law. This statutory protection afforded under the Companies Law to the assets of each SP is one of the key feature and benefit of the SPC structure.

Why is the SPC being used increasingly as a fund structure?

The Cayman Islands continue to be one of the leading offshore jurisdictions for the establishment of hedge funds, private equity funds, real estate funds, and other asset classes. The versatility and efficiency of the SPC structure in terms of the ability to effectively ‘ring fence’ certain assets and liabilities under the same investment portfolio and benefit from statutory recognition of that ring-fencing have made the SPC increasingly attractive in this environment. Like other exempted companies, there are no residency restrictions on Directors or Shareholders of an SPC and there are no Cayman Islands taxes on the SPC or its shareholders.

The SPC corporate structure allows a fund manager to employ different trading strategies, and/or establish different investment platforms, and/or provide access to different markets, and/or different trading advisers through a single corporate vehicle whilst simultaneously providing the segregation of assets and liabilities through each SP. Fund managers are able to market an SPC fund as being able to provide the ability to set up a statutory “ring-fence” to protect against cross liability issues relating to the assets and liabilities of the various SPs within the SPC. The SPC structure is being used as an investment platform on which investors can form different SPs to hold varying asset classes (e.g. real estate, intellectual property, stocks and shares, and distressed assets) and have their investments managed separately from other investments held by other SPs on the same SPC platform.

The SPC will have a Board of Directors. In addition, each SP can have its own segregated portfolio directorate or investment or management committee which effectively controls and manages the operations of the relevant SP. The segregated portfolio directorate, investment or management committee obtains its powers through powers delegated to it by the Board of Directors of the SPC.

This Article first appeared in Asian Legal Business December 2016 Issue – Guide to BVI and Cayman

Gary Smith

The Nuts and Bolts of the Cayman Islands Merger Regime

The Cayman Islands (Cayman) has been the leading offshore jurisdiction for merger and acquisition (M&A) activity over the last three (3) years. In 2015, Cayman-incorporated companies were the target of 863 transactions worth a combined value of USD116.41bn. The value was more than twice the amount of the British Virgin Islands with USD49.62bn (with 387 M&A transactions) and well in excess of Bermuda with 498 M&A transactions with a combined value of USD67.57bni. In 2016, Cayman-incorporated companies again led the way in terms of offshore M&A activity and were the target of transactions worth a combined USD68.85bn followed by the British Virgin Islands with USD41.65bn and Bermuda with USD41.25bnii. By way of comparison, Hong Kong incorporated companies were the target of transactions worth a combined USD33.19bn in 2016iii. Cayman-incorporated companies were the target of transactions worth a total USD80bn in 2017 and USD60bn in the first half of 2018.

The Cayman Merger Law regime is attractive for both companies and investors, due to the process being relatively straightforward and simpler than either a takeover offer (tender offer) under section 88 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law or a court-approved scheme of arrangement under section 86 or 87 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law. Set out below are the basic steps in the process of effecting a merger under Part XVI of the Cayman Islands Companies Law (As Revised).

1. s of the take-private transaction) (the “Buyout Group”) to take on finance and to be ultimately merged with the company which is the target of the take-private (“Target”). Forming MergerCo. The most straightforward structure used for a merger take-private is that a new company (“MergerCo”) is formed in the Cayman Islands by the investors adhering to the takeover group (often involving the founders/managers of the listed company, its parent and/or several private equity (PE) investors acting as sponsors for the purpose

2. Take-Private Offer. After obtaining legal and financial advice, the Buyout Group agrees on the terms of the proposed merger take-private and the consideration which would be offered to the shareholders of the Target and makes an offer to the Board of the Target (the “Initial Take-Private Offer”). Since most of the take-private transactions are initiated by or with involvement of the management or certain shareholders represented at Board level, the merger process requires that a special committee formed of independent directors (the “Special Committee”) be designated to review the take-private offer and negotiate on behalf of the Target with the Buyout Group. This is both to ensure that the Board is in compliance with the fiduciary duties it owes the Target, and to avoid any accusation of self-dealing.

3. Negotiations. The Special Committee reviews and negotiates the offer with the help of its own independent legal and financial advice, which may lengthen the process. Overall, the typical mission of the Special Committee is to: (i) investigate and evaluate the Initial Take-Private Offer, (ii) discuss and negotiate any terms of the merger agreement (the “Merger Agreement”), (iii) explore and pursue any alternatives to the Initial Take-Private Offer as the Special Committee deems appropriate, including maintaining the public listing of Target or finding an alternative buyer, (iv) negotiate definitive agreements with respect to the take-private or any other transaction, and (v) report to the Board the recommendations and conclusions of the Special Committee with respect to the Initial Take-Private Offer.

4. Board Approval. The directors of each company participating in a merger (MergerCo and Target) are required to approve the terms and conditions of the proposed merger (the “Plan of Merger”), including, among other things:

i. how shares in each participating company will convert into shares in the surviving company or other property (e.g. cash payable to shareholders);

ii. what rights and restrictions will attach to the shares in the surviving company;

iv. how the Memorandum and Articles of Association of the surviving company are amended; and

v. what are the amounts or benefits paid or payable to any director consequent upon the merger.

5. Shareholder Approval. For each constituent company (MergerCo and Target), the Plan of Merger is required to be authorized by a special resolution of the shareholders who have the right to receive notice of, attend and vote at the general shareholders’ meeting (“EGM”), voting as one class with at least two-thirds majority.

6. Consents. Each participating company must also obtain the consent of (i) each creditor holding a fixed or floating security interests, and (ii) any other relevant consents or filings with relevant regulatory authorities, such as the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority or authorities in the overseas jurisdiction where the Target is registered and/or operates.

7. Filing and Registration. After obtaining all necessary authorizations and consents, the Plan of Merger is required to be signed by a director on behalf of each participating company and filed with the Cayman Islands Registrar of Companies, who will register the Plan of Merger and issue a certificate of merger.

8. Effective Date. The merger will be effective on the date that the Plan of Merger is registered by the Registrar of Companies unless the Plan of Merger provides for a later specified date or event. Upon the effective date, all rights and assets of each of the participating companies shall immediately vest in the surviving company and, subject to any specific arrangements, the surviving company shall inherit all assets and liabilities of each of the participating companies (MergerCo and Target).

9. Shareholder Dissent. Any shareholder of a company participating in the merger is entitled to payment of fair value of its shares upon dissenting from the merger under Section 238 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law. Fair value can either be agreed between the parties or determined by the Cayman Court.

i Figures from the M&A Latin America and Global Review published by Bureau van Dijk (Zephyr) for the year 2016.

ii Ibid.

iii Figures from the M&A Greater China Review published by Bureau van Dijk (Zephyr) for the year 2016.

iv Or such higher threshold as may be specified in the Memorandum and Articles of Association.

v Or, if the secured creditor fails to grant such consent, the company may apply to the court for a waiver.

vi If date or event is not more than 90 days after the Plan of Merger is registered by the Registrar of Companies.

In the prevailing economic conditions, investors in offshore companies registered in the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) are increasingly being forced to consider their rights against directors who may have been responsible for mismanagement of the company’s affairs. Minority shareholders, in particular, are keen to understand the availability of remedies which allow them to overcome “wrongdoer control”. That is to say, the common situation where the composition and direction of the board is controlled by majority shareholders. We have set out below a brief summary of the duties owed by directors and the remedies available to shareholders in each of these jurisdictions.

What is scope of director’s duties?

Cayman Islands

The duties of a director of a Cayman Company are found in the common law and include the duty to act bona fide in the best interests of the company, a duty not to exercise his or her powers for purposes for which they were not conferred and not to make secret profits.

British Virgin Islands

The law governing the “duties of directors and conflicts” is set out in Division 3 of Part VI of the BVI Business Companies Act, 2004 (as amended) (the “Act”). These largely mirror the position at common law and include, for example, (a) the duty to “act honestly and in good faith and in what the director believes to be in the best interests of the company”(s.120); (b) the duty to exercise powers “for a proper purpose” and a requirement that a director “shall not act, or agree to the company acting, in a manner which contravenes this Act or the memorandum or articles of the company (s.121)”; and a requirement that “a director of a company shall forthwith after becoming aware of the fact that he is interested in a transaction entered into or to be entered into by the company, disclose the interest to the board of the company (s.124). It is interesting to note that subsections 120 (2)-(4) of the Act provide that a director of a company that is a wholly-owned subsidiary, subsidiary or joint venture company may, subject to certain requirements, act in the best interests of the relevant parent, or in the case of the joint venture company, the relevant shareholders even though such act may not be in the best interests of the company of which he is a director.

What are the standard director’s duties?

Cayman Islands

The common law applies to the Cayman Islands such that a director is under a duty to act with reasonable care, skill and diligence in the performance of his or her duties. In the English authority of Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co [1925] Ch. 407 it was held that “a director need not exhibit in the performance of his duties a greater degree of skill than may reasonably be expected from a person of his knowledge and experience. This highly subjective test, however, has been met with increasing criticism in more recent years and there is further English authority to suggest that directors are nevertheless subject to an objective duty to “take such care as an ordinary man might be expected to take on his own behalf” (Dorchester Finance Co v Stebbing [1989] BCLC 498 (decided in 1977)). As such, a distinction appears to be drawn between the duty of skill on the one hand and the duty to take care on the other. However, in Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co it was further held that “in respect of all duties that, having regard to the exigencies of business, and the articles of association, may be properly left to some other official, a director is, in the absence of grounds for suspicion, justified in trusting to that official to perform such duties honestly.”

British Virgin Islands

Section 122 of the Act provides that “A director of a company, when exercising powers or performing duties as a director shall exercise the care, diligence and skill that a reasonable director would exercise in the same circumstances taking into account, but without limitation:

(a) the nature of the company;

(b) the nature of the decision; and

(c) the position of the director and the nature of the responsibilities undertaken by him.”

This duty is qualified by s. 123 to the extent that the director of a company is entitled to rely upon the books of the company in question and/or employees and professional advisers provided that in doing so he or she acts in good faith, undertakes a proper inquiry where this is warranted and has no knowledge of a reason for not placing reliance on the said books and records.

What are the key remedies available to a member or shareholder?

Cayman Islands

The following remedies are available to a member of a Cayman Company:

(a) A personal action against the company (where the company has breached a duty which is owed to the member personally);

(b) A representative action (similar to a personal action such a claim would lie for breach of a duty owed to a group of shareholders)

(c) A derivative, or multiple derivative claim (this is the most common type of action. See below); or

A petition to wind up the company on just and equitable grounds. (This is seen as a last resort because it risks placing the company into liquidation although s.95(3) of the Companies Law (2013 Revision) (the “Law”) provides the Court with the option of making an alternative order. See below).

British Virgin Islands

The members of a BVI company may pursue the following remedies:

(a) A personal action pursuant to section 184G of the Act (on the same grounds as at common law in the Cayman Islands)

(b) A representative action pursuant to section 184H which provides that the Court may appoint a member “to represent all or some of the members having the same interest and may, for that purpose, make such order as it thinks fit, including an order (a) as to the control and conduct of the proceedings; (b) as to the costs of the proceedings; and (c) directing the distribution of any amount ordered to be paid by a defendant in the proceedings among the members represented.

(c) A derivative claim pursuant to section 184C; or

(d) An unfair prejudice claim pursuant to section 184I.

(c) and (d) above are the most common type of remedies sought by minority shareholders (see below).

What are derivative claims and what is their legal basis?

Cayman Islands

A derivative action is a claim commenced by one or more minority shareholders on behalf of a company of which they are a member in respect of loss or damage which that company has suffered. Such a claim can only be brought in certain circumstances and amounts to an exception to the rule that a company, as a separate legal person, should sue and be sued in its own name (often referred to as the rule in the English authority of Foss v Harbottle (1843) 2 Hare 461; 67 E.R 189). In the Cayman Islands the law governing derivative actions is drawn from the common law rather than statute.

British Virgin Islands

While the English common law applies in the British Virgin Islands “members remedies” have been given a statutory footing in Part XA of the Act (see below).

What is the procedure for commencing a derivative action?

Cayman Islands

As with the majority of actions commenced in the Cayman Islands, derivative claims are normally begun by serving a writ and statement of claim on the relevant defendant or defendants. Grand Court Rules O.15, r. 12A provides that where the defendant gives notice of an intention to defend the claim then the plaintiff must apply to the Court for leave to continue the action. Such an application should be supported by affidavit evidence verifying the facts on which the claim and entitlement to sue on behalf of the company are based. Pursuant to Grand Court Rules O.15 r.12A(8) on the hearing of the application, the Court may grant leave to continue the action for such period and upon such terms as it thinks fit, dismiss the action, or adjourn the application and give such direction as to joinder of parties, the filing of further evidence, discovery, cross-examination of deponents and otherwise as it considers expedient. In Renova Resources Private Equity Limited v Gilbertson and Others [2009] CILR 268, Foster., J affirmed the application in the Cayman Islands of the test to be applied in determining whether to grant leave to continue the action put forward by the English Court of Appeal in Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd (No.2) [1981] Ch 257. Foster, J., held that: “(…) there are two elements to this: first the plaintiff [is] required to show prima facie that there [is] a viable cause of action vested in the company and, secondly, that the alleged wrongdoers [have] control of the company (or could block any resolution of the company or the board) and thereby prevent the company bringing an action against themselves.”

British Virgin Islands

Section 184C (1) of the Act provides that subject to certain exceptions “the Court may, on the application of a member of a company, grant leave to that member to (a) bring proceedings in the name and on behalf of that company; or (b) intervene in the proceedings to which the company is a party for the purpose of continuing, defending or discontinuing the proceedings on behalf of the company.” Section 184C(2) provides that “without limiting subsection (1), in determining whether to grant leave under that subsection, the Court must take the following matters into account: (a) whether the member is acting in good faith; (b) whether the derivative action is in the interests of the company taking account of the views of the company’s director’s on commercial matters; (c) whether the proceedings are likely to succeed; (d) the costs of the proceedings in relation to the relief likely to be obtained; and (e) whether an alternative remedy to the derivative claim is available.” Pursuant to subsection (3) leave to bring or intervene in proceedings may be granted “only if the Court is satisfied that: (a) the company does not intend to bring, diligently continue or defend or discontinue the proceedings as the case may be; or it is in the interests of the company that the conduct of the proceedings should not be left to the directors or to the determination of the shareholders or members as a whole. Such an application for leave should be made to the Court supported by affidavit evidence.

Is it possible to bring multiple derivative claims (“MDCs”)?

Cayman Islands

In Renova the Grand Court held that in appropriate circumstances MDCs would be permitted. In that case, the plaintiff had brought an action in respect of loss incurred by a wholly-owned subsidiary of the company in which it was a shareholder and therefore loss to the subsidiary caused indirect loss to its parent company and shareholders. However, the rule against the recovery of reflexive loss applied such that a shareholder or parent company would not be permitted to claim for indirect losses which mirrored those losses suffered directly by the relevant subsidiary or indeed sub-subsidiary on who behalf action was being brought.

British Virgin Islands

In Microsoft Corporation v Vandem Ltd BVIHCVAP2013/0007 the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal held that BVI law which has been codified in this area “does not permit double derivative actions.” That said, recent English authority such as Universal Project Management Services Ltd v Fort Gilkicker Ltd [2013] 3 WLR concerning the interpretation of s.260 the English Companies Act, 2006 may open up arguments that such actions are nevertheless available in the jurisdiction at common law.

What remedies are available for unfair prejudice and what is their legal basis?

Cayman Islands

Pursuant to section 92 of the Companies Law (2013 Revision) the Court may wind up a company if it is of the opinion that it would be just and equitable for it to do so. Section 95(3) provides that where such a petition “is presented by members of the company as contributories on the ground that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up, the Court shall have jurisdiction to make the following orders, as an alternative to a winding-up order, namely –

(a) an order regulating the conduct of the company’s affairs in the future;

(b) an order requiring the company to refrain from doing or continuing an act complained of by the petitioner or to do an act which the petitioner has complained it has omitted to do;

(c) an order authorising civil proceedings to be brought in the name of and on behalf of the company by the petitioner on such terms as the Court may direct; or

an order providing for the purchase of the shares of any members of the company by other members or by the company itself and, in the case of a purchase by the company itself, a reduction of the company’s capital accordingly.

British Virgin Islands

Section 184I of the Act provides that “a member of a company who considers that the affairs of the company have been, are being or are likely to be, conducted in a manner that is, or any act or acts of the company have been, or are, likely to be oppressive, unfairly discriminatory, or unfairly prejudicial to him in that capacity, may apply to the Court for an order under this section.” Section 184I(2) provides that “if on an application under this section, the Court considers it just and equitable to do so, it may make such order as it thinks fit, including, without limiting the generality of this subsection, one or more of the following orders:

(a) in the case of a shareholder, requiring the company or any other person to acquire the shareholder’s shares;

(b) requiring the company or any other person to pay compensation to the member;

(c) regulating the future conduct of the company’s affairs;

(d) amending the memorandum and articles of the company;

(e) appointing a receiver of the company;

(f) appointing a liquidator of the company under section 159(1) of the Insolvency Act on the grounds specified in section 162(1)(b) of that Act;

(g) directing the rectification of the records of the company;

setting aside any decision made or action taken by the company or its directors in breach of this Act or the memorandum or articles of the company.

This Briefing Note is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. It deals in broad terms only and is intended to merely provide a brief overview and general guidance only. For more specific advice on the laws in the Cayman Islands, please contact:

In the previous issues of our series of legal insights on owning intellectual property (IP) through a Cayman Islands corporate structure, we presented a brief overview of the new trademark registration process which became effective in the Cayman Islands as at 1st August 2017 (see The New Cayman Islands Trademarks Regime).

In the meantime, blockchain technologies and ICOs have gained increasing popularity all over the world and in the Cayman Islands as well (see our FinTech series including Top Ten Risks for the Crypto-Currency Investor: A View from the Cayman Islands and Cayman Islands Legal Perspective on the Regulation of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs)).

Confident in the security and their uniqueness or blinded by the open source aspects of their technology, blockchain start-ups may tend to forget one of the basic tenets of entrepreneurship: making certain that any newly generated intellectual property is well-protected. Beyond block-chain technology, commercial names and trademarks may become extremely valuable. If a block-chain start-up incorporates in the Cayman Islands, it now has the option of registering its name and logo in the Cayman Islands as well, providing additional protection after the launch or the projected Initial Coin Offering (ICO) or Initial Token Offering (ITO).

Three Simple Steps to Register Name & Logo:

Be Original & Distinctive: A trade mark1 which lacks distinctive character, which is customary in the current language or the established practices of the trade, or which designates characteristics of goods or services will be refused from registration.

Check Availability: Identical or similar trade marks cannot be registered for similar services, while similar trade marks may only be registered subject to the consent of the holder of the earlier mark2 . In addition, trade marks which take unfair advantage of, or are detrimental to, the character or the repute of an earlier similar mark registered or otherwise protected in the Cayman Islands3 will not be accepted.

File Early: Once accepted, the trade mark will be published in the Intellectual Property Edition of the Cayman Islands Gazette, which triggers a sixty (60) day period for oppositions4 . From a strategic point of view, it is best to launch after the opposition period had lapsed and the trade mark registration is secured.

See also, for more information regarding the trademark registration and intellectual property pro-tection for FinTech companies, our alerts on The New Cayman Islands Trademarks Regime and Financial Technology Intellectual Property (FinTech IP) Welcome in the Cayman Islands.

1. Article 23(1) of the Trade Marks Law, 2016

2. Article 25(6) of the Trade Marks Law, 2016

3. Article 25(3) of the Trade Marks Law, 2016

4. Article 16(2) of the Trade Marks Law, 2016

This is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact:

Ramona Tudorancea

Corporate / M&A Specialist

E: ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

W: www.loebsmith.com

The Cayman Islands have now brought into effect the long-awaited Limited Liability Companies Law, 2016 (the “LLC Law”) which introduces a new Cayman Islands limited liability company (an “LLC”). The LLC Law was published on 8th June 2016 but had not been brought into effect until 8th July 2016 in order to provide the Companies Registry with sufficient time to implement internal systems for dealing with registration of new LLCs. The Companies Registry is currently undertaking pilot testing of its internal systems and has advised that it expects to be able to accept registration applications for new LLCs before 15th July 2016.

Key Features of Cayman LLCs

- An LLC formed under the LLC Law will be similar in structure to that of the Delaware LLC as the LLC Law is broadly based on the Limited Liability Company Act in the State of Delaware. However, the LLC Law has also preserved the broad legal principles applicable to Cayman Islands companies and the rules of equity and common law. Section 3 of the LLC Law expressly states that: “The rules of equity and of common law applicable to companies registered in the Islands, as modified by the Companies Law and any other Laws in force in the Islands applicable to such companies, shall apply to a limited liability company, except in so far as such rules and law or modifications thereto are inconsistent with the express provisions of this Law or the nature of a limited liability company”.

- An LLC is a corporate entity which has separate legal personality to its members.

- Formation of an LLC is straightforward. It requires the filing of a registration statement with the Companies Registry and payment of the requisite Government fee.

- An LLC must have at least one member. It can be member managed (by some or all of its members) or the LLC agreement can provide for the appointment of persons (who need not be members) to manage and operate the LLC.

- The liability of an LLC’s members is limited. Members can have capital accounts and can agree amongst themselves (in the LLC agreement) how the profits and losses of the LLC are to be allocated and how and when distributions are to be made (similar to a Cayman Islands exempted limited partnership).

- An LLC may be formed for any lawful business, purpose or activity and it has full power to carry on its business or affairs unless its LLC agreement provides otherwise.

- An LLC may (but is not required to) use one of the following suffixes in its name: “Limited Liability Company”, “LLC” or “L.L.C.”.

- The following statutory registers are required to be maintained for an LLC but, similarly to the requirement for a Cayman Islands exempted company, only an LLC’s register of managers is required to be filed with the Companies Registry:

-

- a register of members;

- a register of managers; and

- a register of mortgages and charges.

The register of managers and register of mortgages and charges are required to be maintained in a manner similar to the register of directors and register of mortgages and charges for a Cayman Islands exempted company.

- Subject to any express provisions of an LLC agreement to the contrary, a manager of the LLC will not owe any duty (fiduciary or otherwise) to the LLC or any member or other person in respect of the LLC other than a duty to act in good faith in respect of the rights, authorities or obligations which are exercised or performed or to which such manager is subject in connection with the management of the LLC provided that such duty of good faith may be expanded or restricted by the express provisions of the LLC agreement.

Expected Benefits of the New LLC Vehicle

Under the LLC Law, it is now possible to:

- Form and register a new LLC;

- Convert an existing Cayman Islands exempted company into an LLC;

- Merge an existing Cayman Islands exempted company into an LLC; and

- Migrate an entity formed in another jurisdiction (e.g. Delaware) into the Cayman Islands as an LLC.

It is expected that the new Cayman Islands LLC structure will be attractive for general partner entities and other carried interest distribution vehicles. It may also prove attractive for management company entities and possibly for offshore funds in order to align the rights of investors between onshore and offshore investment funds in a master/feeder structures.

For Specific advice on Cayman Islands limited liability companies, please contact either of:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E yun.sheng@loebsmith.com

The Cayman Islands Government has issued The Confidential Information Disclosure Bill, 2016 (“Confidentiality Bill”) which, once it comes into force will bring into effect a fundamental overhaul of confidentiality laws in the Cayman Islands.

The introduction of the Confidentiality Bill is part of a series of actions being taken by the Cayman Islands Government to the assist global efforts to increase transparency.

Existing Law

Under the existing law, which is found in The Confidential Relationships (Preservation) Law (2015 Revision), it is a criminal offence to divulge or attempt, offer or threaten to divulge “confidential information” (which is defined as including information concerning any property which the recipient thereof is not, otherwise than (in the narrowly construed exception of) “in the normal course of business”, authorised by the principal to divulge) except in a limited number of specified circumstances.

Notwithstanding the criminal penalties that follow a breach of the existing law, there has not been a criminal conviction under the existing law since its original enactment over 40 years ago.

The prohibition applies with respect to business of a professional nature (e.g. the relationship between a bank, trust company, an attorney-at-law, an accountant, an estate agent, an insurer, or a broker and its client) which arises in or is brought to the Cayman Islands and to all persons coming into possession of such information at any time thereafter whether they be within the jurisdiction or not.

As mentioned above, disclosure is permitted in a number of specified circumstances (e.g. (i) in respect of any professional person acting in the normal course of business, or with the consent, express or implied, of the relevant principal; or (ii) in response to statutory requests from certain criminal or regulatory authorities (e.g. the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority), or (iii) a court order).

Proposed new Law

The Confidentiality Bill proposes the following key amendments:

It will no longer be a criminal offence to breach a duty of confidentiality.

In future it will be necessary to assess whether the information imparted was subject to a duty of confidence in the first place. This will effectively shift the burden of proof from showing that the disclosure falls within an exception to the current prohibition, to showing that the information imparted was in fact subject to a duty of confidence.

Where a person owes a duty of confidence, that person’s disclosure of such information within a widened list of specified circumstances will not constitute a breach of the duty of confidence and a person will not be able to sue the discloser.

A person who discloses confidential information in relation to a serious threat to the life, health, safety of a person or in relation to a serious threat to the environment will have a defence to legal action for breach of a duty of confidence, as long as the person acted in good faith and in the reasonable belief that the information was substantially true and disclosed evidence of a serious threat to life, health, safety of a person or of a serious threat to the environment.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. It deals in broad terms only and is intended to merely provide a brief overview and general guidance only. For more specific advice on the confidentiality laws in the Cayman Islands, please contact:

Gary Smith

Partner

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

As the deadline for the filing of notifications to the Cayman Islands Tax Information Authority via the Cayman AEOI Portal in respect of (i) entities formed in 2015 for U.S. FATCA purposes and (ii) entities for UK CDOT purposes, approaches on 10 June 2016, we revisit some of the key issues on the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) and its application to Cayman Islands formed Investment Entities.

For specific advice on U.S. FATCA, UK CDOT, and the CRS as they relate to Cayman Islands entities, please contact any of:

E lorna.williams@loebsmith.com

Gary Smith

Partner

Introduction

A Cayman Islands company can be dissolved by the appointment of a liquidator or it can be dissolved without such appointment if the company is struck off the register as a result of an application to the Registrar of Companies for the purpose.

Voluntary liquidation

In circumstances where the company has been active and has substantial assets and liabilities, it is normal and recommended for the company to be liquidated.

If a liquidation is pursued the company would normally agree the liquidation fee with the liquidator and will often be requested to provide the liquidators with an indemnity. Voluntary winding-up (liquidation) pursuant to the Companies Law (as Revised) (the “Law”) involves the following procedures:

Directors meeting

The Directors commence a voluntary winding-up by holding a meeting of the Board of Directors to give notice to the shareholders that an Extraordinary General Meeting of Shareholders is to be held to consider the passing of a Special Resolution that the company be placed in voluntary liquidation.

Shareholders’ meeting

The Directors, or if one is appointed, the secretary of the company should circulate the appropriate notice convening the meeting. The appropriate period of notice will be determined by reference to the company’s Articles of Association and the Companies Law as the period for a special resolution. The shareholders of the company pass a special resolution that the company be voluntarily wound up and a liquidator appointed. Alternatively, if the Articles of Association permit it, a written resolution may be signed by all the members of the company.

A special resolution is one which is passed by a two thirds majority of the shareholders present at a meeting duly convened by notice specifying the time and place of the meeting and the resolution to be passed. Alternatively, and if so provided for in the Articles of Association of the company, the special resolution may take the form of a circular resolution. However, this type of resolution has to be approved in writing by all of the members entitled to vote at a general meeting of the company.

A copy of the special resolution is then filed with the Registrar of Companies and the liquidation commences.

Public notice

Notice of the special resolution winding up the company and appointing the joint liquidators is published in the Cayman Islands Gazette advising of the liquidation and advertising for creditors to come forward. The Liquidator then proceeds to collect the assets and discharge the liabilities of the company.

If the date of the final meeting of shareholders can be established at this stage (i.e. the company has no assets or liabilities) notice of the date of the final meeting can be placed in the Gazette at this time.

As soon as the affairs of the company are fully wound up, the liquidators advertise by public notice or otherwise as the Registrar o f C o m p a n i e s may direct, the time, place and object of the final general meeting of the company, which is to be held not less than one month after the date the notice is published, for the purposes of explaining the final accounts of the liquidation. If the company has no assets or liabilities and the date of the final meeting has already been set at the time that the notice of liquidation was published, the liquidator may proceed to hold the final meeting.

Liquidators’ reports

In the terms of the statutory insolvency provisions, the liquidators must report back to the shareholders of the company periodically through the liquidation process so as to keep them informed of the collection and realisation of assets and the settlement of liabilities. All such meetings will be convened at the instance of the joint liquidators.

An interim report by the liquidators will provide detail of the assets identified and the liabilities claimed and accepted as being due and owing. The report may also indicate what, if any, dividend is to be paid on liabilities including any distribution that is anticipated for the benefit of the shareholders.

The liquidation itself is concluded after the liquidators have provided their final report to the shareholders. The liquidators will, once again, convene the appropriate meeting and present their final report. After the conclusion of that final meeting, the liquidators must file a notice confirming that the meeting has been held and the appropriate resolutions approved to conclude liquidation.

Consequences of Voluntary winding-up

The following consequences shall ensue upon the voluntary winding-up of the company:

Voluntary winding-up and dissolution is taken to have commenced on the date of the special resolution referred to above.

The company from the date of commencement of winding up ceases to carry on its business, except in so far as may be required for the beneficial winding up thereof. However all of the company’s corporate powers shall continue until the affairs of the company are wound up.

The property of the company shall be applied in satisfaction of its liabilities pari passu and subject thereto, shall, unless it be otherwise provided by regulations of the company, be distributed amongst the members according to their rights and interests in the company.

Upon appointment of the liquidators all the powers of the directors shall cease, except insofar as the company, by resolution of its shareholders or the liquidators, may sanction the continuation of such powers. All transfers of shares and any alteration to the status of the shareholders of the company requires the sanction of the liquidator.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. It deals in broad terms only and is intended to merely provide a brief overview and general guidance only. For more specific advice on voluntary winding-up of Cayman Islands companies, please contact:

Gary Smith

Yun Sheng

Introduction

Why segregated portfolio companies are thriving in Cayman? Loeb Smith’s corporate Partner Gary Smith talks to HFM Week about SPCs.

HFMWeek (HFM): How versatile are SPCs? What makes them this way?

Gary Smith (GS): Under Cayman Companies Law, a segregated portfolio company (SPC) is an exempted company which has been registered as a segregated portfolio company. It has full capacity to undertake any object or purpose, subject to any restrictions imposed on the SPC in its Memorandum of Association. The Memorandum of Association of an SPC usually gives the SPC full capacity to pursue very broad objects. Once registered under the Cayman Islands Companies Law, an SPC can operate segregated portfolios (SPs) with the benefit of statutory segregation of assets and liabilities between portfolios.

The appeal of SPCs extends beyond investment funds and is often used in capital markets and securitisation transactions. In the investment funds context, SPCs greatly enhance the versatility and efficiency of Cayman Islands fund structures. It allows investors to access different trading strategies or investments, different markets or different managers through a single corporate vehicle whilst simultaneously providing the segregation of assets and liabilities through each SP. This feature is unlike, for example, a ‘multi-class’ fund where there is typically a single legal entity offering various classes of shares designated according to the portfolio investment. The statutory ring-fence of assets and liabilities of an SP affords the SPC structure the ability to avoid cross class liability issues which could arise with ‘multi-class’ funds.

Cayman Islands Companies Law permits an SPC to create one or more SPs in order to segregate the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within one SP from the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within another SP of the SPC. The general assets and general liabilities of the SPC (i.e. assets and liabilities which cannot be properly attributed to a particular SP) are held within a separate general account rather than in any of the SP accounts. Each SP should have, as appropriate, its own bank account, brokerage account, and other accounts to hold its assets to avoid co-mingling with the assets of other SPs.

The Companies Law requires that segregated portfolio assets must only be available and used to meet liabilities to the creditors of the SPC who are creditors in respect of that SP, and who will, as a consequence, be entitled to have recourse to the segregated portfolio assets attributable to that SP for such purposes. Segregated portfolio assets of an SP should not be available or used to meet liabilities to, and shall be absolutely protected from, the creditors of the SPC who are not creditors in respect of that SP, and who accordingly will not be entitled to have recourse to the segregated portfolio assets attributable to that SP.

Accordingly, a creditor will only have recourse to assets from SPs with which it has contracted and creditors will have no recourse to the assets of other SPs of the SPC which are protected under the Companies Law. This statutory protection afforded under the Companies Law to the assets of each SP is one of the key feature and benefit of the SPC structure.

HFM: Why are SPCs flourishing in the Cayman Islands?

GS: The SPC corporate structure allows a fund manager to employ different trading strategies, and/or establish different investment platforms, and/or provide access to different markets, and/or different trading advisers through a single corporate vehicle while simultaneously providing the segregation of assets and liabilities through each SP. Fund managers are able to market an SPC fund to potential investors as being able to provide a statutory ‘ring-fence’ to protect against cross liability issues relating to the assets and liabilities of the various SPs within the SPC.

The SPC structure is increasingly being used as an investment platform on which investors can use different SPs to hold varying asset classes (e.g. real estate, intellectual property, stocks and shares, and distressed assets) and have their investments managed separately from other investments held by other SPs on the same SPC platform. We have seen an increase in the use of SPCs by fund managers as investment platforms for pursuing different strategies for the same pool of investors, managing investments in different geographical regions (e.g. China and emerging markets in Asia and Africa) and investing in different sectors (clean technology and offshore oil drilling). The SPC will have a board of directors. In addition, each SP can have its own segregated portfolio directorate or investment or management committee which effectively controls and manages the operations of the relevant SP. The segregated portfolio directorate, investment or management committee would obtain its powers through powers delegated to it by the board of directors of the SPC.

The liabilities to a person arising from a matter imposed on, or attributable to, a particular SP, only entitle that person to have recourse to that particular SP in the first instance and then to the general assets of the SPC, unless the Articles of Association of the SPC prohibits payments from the general assets of the SPC, in which case there is no recourse to the general assets.

HFM: Are there any misconceptions about SPCs? What are they?

GS:

Can assets be transferred between SPs? The Companies Law requires the directors of the SPC to ensure that assets and liabilities are transferred between SPs at full value.

Does an SP have separate legal personality? While the SPC is a company and therefore a corporate entity with separate legal personality, an SP does not have separate legal personality. Accordingly, the Companies Law requires that when contracting on behalf of a particular SP, it should be made clear which SP of the SPC is contracting on behalf. Each SP can have its own investment manager, trading advisor, and other service providers but it should be made clear in the agreements which SP of the SPC has engaged them for their services.

Can an SP be liquidated without liquidating the entire SPC? An application can be made to the Cayman Court for a receivership order where a particular SP of the SPC is insolvent and other SPs within the SPC are operating on a solvent basis.

Gary Smith is a partner in Loeb Smith’s corporate team advising principally on offshore investment funds, IPOs and M&A. Gary has given expert evidence in the United States Bankruptcy Courts relating to Cayman Islands investment funds and has also authored various publications on issues pertaining to Cayman Islands funds. For more information please contact:

Gary Smith

Partner

Structure of Cayman Private Equity Funds

The most common structure for a Cayman Islands domiciled private equity fund (“PE Fund”) is as an exempted limited partnership (“ELP”) formed under the Exempted Limited Partnership Law (As Revised) (“ELP Law”). However there are some Fund sponsors who choose a Cayman exempted company rather than an ELP as the corporate structure for their PE Funds for a number of reasons, including, onshore tax or regulatory considerations, or the investor base are more familiar with or prefer to invest in a Cayman exempted company.

The ELP is required to have a general partner (“GP”) which is most commonly a Cayman exempted company. However a foreign company (e.g. a limited liability company) has been able to be the GP of an ELP upon registration as a foreign company in the Cayman Islands. A partnership established outside the Cayman Islands was not previously able to act as a GP of an ELP. The list of persons who qualify as a GP of an ELP has been extended to include a limited partnership or limited liability partnership established in a recognized jurisdiction (e.g. United States, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, BVI, Singapore, Jersey, Luxembourg) (a “foreign limited partnership”) provided such foreign limited partnership is registered as a foreign limited partnership in the Cayman Islands.

The GP is responsible for conducting the management of the affairs of the ELP and is ultimately liable for all debts and obligations of the ELP to the extent that the ELP has insufficient assets. The GP will sign all contracts on behalf of and in the name of the ELP.

The Directors and shareholders of the GP are typically persons who are affiliated with the sponsor of the PE Fund. There is no requirement for any Director or shareholder of the GP to reside in the Cayman Islands. The limited partners of the ELP will be the investors subscribing for equity interests in the PE Fund. There are no restrictions on the number of investors that may be admitted to an ELP. There is no requirement for any limited partner of the ELP to reside in the Cayman Islands.

Main Features of the ELP

The ELP Law adopts principles similar to those found in the Delaware Revised Uniform Limited Partnership Act, and this similarity with the Delaware model makes the ELP particularly attractive to managers and investors in the United States. However, unlike a Delaware limited partnership, an ELP does not have a legal personality of its own. The ELP is a legal arrangement between its GP and its limited partners and the terms of this legal arrangement is governed principally by the terms of the limited partnership agreement (“LPA”). The contractual rights and equitable interests in the assets of the ELP are held on trust for the ELP by its GP (and, if there is more than one GP, by the general partners jointly)

Not having its own legal personality, the ELP is generally regarded from an onshore tax perspective as being tax transparent (or as having “see-through”, “look-through” or “flowthough” status, which signify the same thing) with the effect that the ELP itself will not be liable to any onshore taxes, and value distributed by it will “flow-through” to the investors (and may be subject to local taxes in their hands).

A limited partner may not participate in the conduct of the ELP’s business, and all contractual documents and papers must be executed by the GP as the contracting party acting on behalf of the ELP. Any limited partner participating in this way, as though it were a GP, will be liable for the debts and obligations of the ELP, if it goes insolvent, to any person transacting business with the ELP through the limited partner and who had actual knowledge of such limited partner’s participation and who reasonably believed that limited partner to be a general partner.

The ELP Law set outs certain non-exhaustive “safe harbours” of activities in which a limited partner may engage without risk of losing its limited liability status; a limited partner’s participation on an advisory board or investment committee of the PE Fund will typically be within the safe harbours. The LPA may nonetheless provide for any amount of limited partner participation in the conduct of the ELP’s business.

Under the previous ELP law, a GP was under an absolute duty to act in good faith in the interest of the ELP. This duty could not be restricted, limited or varied by the terms of the LPA between the GP and the LPs. The requirement to act in the interest of the ELP often raised the issue of conflicts of interest for the GP, particularly when it acted as GP to more than one ELP. A GP which acted as the sole GP to several private equity funds (structured as ELPs) had to, for example, consider how to discharge its statutory duty to act in good faith in the interest of each fund, in relation to investment opportunities. The ELP Law, which came into force on 2nd July 2014 with the aim of enhancing the attractiveness of the Cayman Islands as the leading offshore jurisdiction for private equity funds, retained the absolute duty on the GP to act in good faith. However, whilst retaining the duty on the GP to act in the interest of the ELP, makes it subject to any express provision in the LPA to the contrary.

A limited partner of an ELP owes no fiduciary duty to any other partners of the ELP or to the ELP itself in exercising any of its rights or performing any of its obligations under the LPA, except to the extent that it has expressly agreed to such fiduciary obligations in the LPA. Partners may nevertheless agree to set out certain fiduciary obligations in the LPA. They might, for example, agree to impose fiduciary duties on members of advisory boards or committees of the ELP.

Regulation

As a general matter, closed-ended funds (e.g. a private equity fund or a real estate fund), however structured, are not regulated by the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (“CIMA”) under the Mutual Funds Law (2015 Revision) because the equity interests issued by the ELP are not redeemable or repurchaseable at the option of investors. In addition, the PE Fund’s GP does not require any form of approval or licensing in the Cayman Islands.

Timing

Formation and registration of an ELP and its GP can take place either on a same-day express basis with the payment of an express fee of approximately US$488 or within 2-3 business days on a standard basis.

Taxation

There are no capital gains, income, withholding, estate or inheritance taxes in the Cayman Islands. The ELP can apply for (and can expect to obtain) an undertaking from the Cayman Islands government that no form of taxation that may be introduced in the Cayman Islands will apply to the ELP for a period of 50 years from the undertaking being given. The GP can also apply for (and can expect to obtain) an undertaking from the Cayman Islands government that no form of taxation that may be introduced in the Cayman Islands will apply to the GP for a period of 20 years from the undertaking being given.

This Briefing Note is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. It deals in broad terms only and is intended to merely provide a brief overview and general guidance only. For more specific advice on the Cayman Islands companies, please refer to your usual Loeb Smith contact or: