About Loeb Smith

People

Sectors

Expertise

- Legal Service

- Banking and Finance

- Blockchain, Fintech and Cryptocurrency

- Capital Markets and Privatization

- Corporate

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy

- Insolvency, Restructuring and Corporate Recovery

- Insurance and Reinsurance

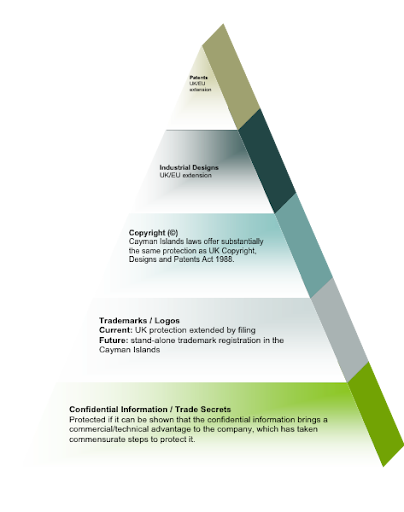

- Intellectual Property

- Investment Funds

- Litigation and Dispute Resolution

- Mergers and Acquisitions

- Private Client and Family Office

- Private Equity and Venture Capital

- Governance, Regulatory and Compliance

- Entity Formation and Managed Services

- Consulting

- Legal Service

News and Announcements

Locations

Subscribe Newsletters

Contact

Introduction

In general, the rights of shareholders of Cayman Islands domiciled companies are governed by the provisions of the Companies Law (2018 Revision) as amended (the “Companies Law”) and the provisions contained in the Memorandum of Association (“Memorandum”) and Articles of Association (“Articles”) of the company. Section 25(3) of the Companies Law states that, when registered, the Articles bind the company and its members to the same extent as if each member had subscribed his name and affixed his seal thereto, and there were in such Articles contained a covenant on the part of himself, his heirs, executors and administrators to conform to all the regulations contained in such Articles subject to the Companies Law. The Articles therefore creates a statutory contract between the members and the company. Each shareholder by agreeing to be a member of the company agrees to be bound by the voting provisions set out in the Articles and subject to the decisions of the majority or special majorities required under the Companies Law and the Articles

The provisions of the Companies Law which govern minority shareholder protection are to a large extent derived from the equivalent provisions in English law. However there are some differences.

Unfair Prejudice

Unlike under English law, there is no ability for a shareholder of a Cayman Islands company to bring a petition before the Cayman Islands Grand Court (the “Court”) on the basis of “unfair prejudice”. However under section 95(3) of the Companies Law, the Court hearing a just and equitable winding-up petition has the discretion to grant alternative remedies to a winding-up, which are the same as the remedies which an English court can grant on an “unfair prejudice” petition, including the following:

an order regulating the conduct of the company’s affairs in the future;

an order requiring the company to refrain from doing or continuing an act complained of by the petitioner or to do an act which the petitioner has complained it has omitted to do, or

an order authorising civil proceedings to be brought in the name and on behalf of the company by the petitioner on such terms as the Court may direct; or

an order providing for the purchase of the shares of any members of the company by other members or by the company itself and, in the case of a purchase by the company itself, a reduction of the company’s share capital accordingly).

Right to Information

A shareholder of a Cayman Islands company has no right by virtue of his position as shareholder to be provided with information regarding the company, including the company’s accounts unless such a right is specifically stated in the Articles, or has been agreed by contract (e.g. in a shareholders agreement) which is binding on the company. A search request can be submitted to the Cayman Islands Companies Registry in respect of the company but the only information a search will reveal is the company’s name, number, formation date, type, registered office and status.

Under section 64(b) of the Companies Law, the Court may appoint one or more competent inspectors to examine into the affairs of a company and to report thereon to the Court in such manner as the Court may direct on the application of the holders of not less than one-fifth (1/5) of a company’s issued and outstanding shares. Section 65 of the Companies Law states that it is the duty of all officers and agents of the company to produce for examination by an inspector all books and documents in their custody or power; any inspector may examine upon oath the officers and agents of the company in relation to its business, and may administer such oath accordingly; and any officer or agent who refuses or neglects to produce any book or document directed to be produced, or to answer any question relating to the affairs of the company, shall incur a penalty in respect of each such offence.

Right to bring Personal Action

A shareholder in a company may be able to bring an action directly against the company’s directors if the shareholder can show that the directors have breached a duty owed to the shareholder personally (instead of a duty owed to the company). However actions against directors for breach of their duties, are typically brought to enforce a right belonging to the company rather than to one or more shareholders and accordingly such actions brought to enforce a right belonging to the company, as a general rule of law, have to brought by the company itself (i.e. the right will lie with the Board of Directors of the company for and on behalf of the company).

Derivative Actions

As stated above, the general principle is that an action seeking to enforce a right belonging to a company has to be brought by the company itself. This rule derives from the English common law case of Foss v. Harbottle [1843] 2 Hare 461. The Cayman Islands Court of Appeal has affirmed this principle in two cases: Schultz v Reynolds [1992-93] CILR 59; and Svanstrom v Jonasson [1997] CLLR 192.

Since the right to bring an action to enforce a right belonging to the company belongs to the company, the litigation has to be brought by the company itself. Normally, a company’s Articles will state that the right to commence litigation will lie with the company’s Board of Directors. The shareholder(s) will therefore need to persuade the directors to bring an action on behalf of the company. If the directors decline to take this action, the shareholder(s) would then typically want to consider whether they can replace the directors with a newly constituted Board, who can then initiate the action against the former directors. The procedure for removal and replacement of directors will be set out in the Articles.

There will be instances when a shareholder, who is in the minority on a vote at a general meeting, will wish to object to the result. Generally speaking, a shareholder will object to the result of a vote in circumstances where (X) in the shareholder’s view, harm will result to the company (and consequently the value of the shareholder’s shareholding), or (Y) the shareholder’s personal rights as shareholder have been infringed.

The English common law case of Foss v. Harbottle mentioned above, has also been extended to cover the principle that “an individual shareholder cannot bring an action in the courts to complain of an irregularity (as distinct from an illegality) in the conduct of the Company’s internal affairs if the irregularity is one which can be cured by a vote of the Company in general meeting” (Prudential Assurance Co. Ltd. v Newman Industries (No. 2) [1982] Ch. 204, C. A,). This is often referred to as the second limb of the rule in Foss v Harbottle. The reason behind what is known as the second limb of the rule in Foss v Harbottle was the courts desire to avoid futile litigation. If the thing complained of was an action which in substance was something the majority of the company’s shareholders were entitled to do, or if something has been done irregularly which the majority of the company’s shareholders are entitled to do regularly, there was no point in having litigation about it as the ultimate result of the litigation would be that a general meeting of the company’s shareholders has to be called and ultimately the majority gets its way (per Mellish LJ in MacDougall v. Gardiner).

The result of these combined principles is that a minority shareholder can seldom bring an action in his own name against those in control of the company where the action is in respect of a wrong done to the company. The minority shareholder will simply not have locus standii to do so. Furthermore, it will be difficult for a minority shareholder to use the name of the company to bring an action (i.e. a derivative action).

However, based upon established English case law authorities, if the shareholder can bring himself within one of the exceptions to the rule in Foss v Harbottle, the shareholder may be able to bring a derivative action, whereby he or she may bring an action in his or her own name but on behalf of the company. The exceptions are as follows:

where the alleged wrong is ultra vires (i.e. beyond the capacity of) the company or illegal;

where the action complained of is an irregularity in the passing of a resolution which could only have been validly done or sanctioned by a special resolution or special majority of shareholders (i.e. a majority which is more than a simple majority of over 50%);

where what has been done amounts to a “fraud on the minority” and the wrongdoers are themselves in control of the company, so that they will not cause the company to bring an action; and

where the act complained of infringes a personal right of the shareholder seeking to bring the action.

Where the Acts amount to a Fraud on the Minority and the Wrongdoers are themselves in control of the Company

The reason for this exception is that if minority shareholders were denied the right to bring an action on behalf of themselves and all others in such circumstances, their grievance would never reach the court because the wrongdoers themselves, being in control, would not allow the company to sue. In order for this exception to apply, first it must be shown that there has been a fraud within the meaning of that word in the English case law authorities on this area and second, it must be shown that the wrongdoers are in control so that the minority shareholder is being improperly prevented from bringing a legal action in the name of the company. In this context, fraud is thought to comprise “fraud in the wider equitable sense of that term, as in the equitable concept of a fraud on a power”. Fraud does not include pure negligence, however gross. The traditional approach that appears to have been followed by English courts in the circumstances is to examine the nature of the act complained of to determine whether it is ratifiable by the majority and if it is not, then it will amount to a fraud on the minority. Based on English case law authorities (which are persuasive authority in the Cayman Islands), the following points can be made:

The misappropriation of the company’s property or assets by the majority for their benefit, at the expense of the minority, is an act which can be interfered with by the Court at the suit of the minority, since it is not ratifiable by the majority.

Many breaches of directors’ duties are ratifiable by the majority shareholders in general meeting, and in these circumstances the minority will have no remedy. Therefore, for example, in the case of Pavlides v. Jensen where it was alleged that the directors were grossly negligent, but not fraudulent, in selling property of the company at an under-value, this was ratifiable by the majority.

There may be circumstances in which the majority shareholders do not exercise their powers bona fide for the benefit of the company as a whole which could amount to a fraud on the minority.

As stated above, an individual shareholder will only be permitted to bring an action in respect of a fraud on the minority if he shows that the company is controlled by the wrongdoers. The meaning of control in this context is not clear although it covers voting control, even where shares are held by nominees.

The question of whether or not there has been a fraud in the sense discussed above and whether or not the wrongdoers are in control of the company must be determined before the minority shareholder’s action is allowed to proceed.

Just and Equitable Winding Up

An alternative remedy to taking a derivative action for an aggrieved shareholder would be to petition the Cayman Islands court on the basis that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up under Section 92(e) of the Companies Law. If a winding-up order is made, liquidators will be appointed who can then investigate the company’s affairs and pursue claims against the former directors (and any others who have caused loss to the company).

As stated above, under section 95(3) of the Companies Law, the Cayman Islands courts hearing a just and equitable winding-up petition has the discretion to grant alternative remedies to a winding up of the company (see Unfair Prejudice above).

Schemes of Arrangement

Sections 86 to 88 of the Companies Law set out provisions regarding schemes of arrangement that may be entered in relation to the company pursuant to which a minority shareholder may be bound by the actions of the majority specified in such provision. We would draw your attention to the provisions of Section 88 which set out the powers to acquire the shares of dissenting shareholders.

Dissenting Rights under the Cayman Merger Law Regime

Section 238 of the Companies Law, provides a shareholder of a Cayman Islands company, involved in a merger or consolidation under the merger regime set out in Part XVI of the Companies Law with the entitlement to be paid the fair value of his or her shares upon dissenting from the merger or consolidation.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of:

ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

santiago.carvajal@loebsmith.com

(per McGarry V-C in Estmanco (Kilner House) Ltd. v. GLC [1982] 1 All ER 437).

(Pavlides v. Jensen [1956] 2 All ER 518).

(Menier v. Hooper’s Telegraph Works [1874] LR 9 CH APP 350), (Cook v. Deeks [1916] 1 AC 544).

(Estmanco (Kilner House) Ltd. v. GLC).

(Russell v. Wakefield Waterworks Co. [1875] LR 20 EQ 474).

(Pavlides v. Jensen [1956] 2 All ER 518).

(Prudential Assurance Co. Ltd. v. Newman Industries Ltd. (No. 2) [1980] 2 All ER).

Introduction

Could you briefly explain the concept of the Segregated Portfolio Company?

Once registered under the Cayman Islands Companies Law, a segregated portfolio company (“SPC”) can operate segregated portfolios (“SPs”) with the benefit of statutory segregation of assets and liabilities between portfolios.

Under Cayman Companies Law, an SPC is an exempted company which has been registered as a segregated portfolio company. It has full capacity to undertake any object or purpose subject to any restrictions imposed on the SPC in its Memorandum of Association (“Memorandum”). The SPC is able to create one or more SPs in order to segregate the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within one SP from the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within another SP of the SPC.

The general assets and general liabilities of the SPC (i.e. assets and liabilities which cannot be properly attributed to a particular SP) are held within a separate general account rather than in any of the SP accounts.

This statutory requirement for an SPC to make a distinction between “segregated portfolio assets” (i.e. assets of the SPC designated or allocated for the account of a particular SP of the SPC) and general assets (i.e. assets of the SPC not designated or allocated for the account of any particular SP of the SPC) and similarly the distinction between “segregated portfolio liabilities” (i.e. liabilities of the SPC designated or allocated for the account of a particular SP) and general liabilities means that each SP should have, as appropriate, its own bank account, brokerage account, and other accounts to hold its assets to avoid co-mingling with the assets of other SPs and out of which liabilities can be satisfied. It is the duty of the Directors of the SPC to establish and maintain (or cause to be established and maintained) procedures:

to segregate, and keep segregated, portfolio assets separate and separately identifiable from general assets;

to segregate, and keep segregated, portfolio assets of each SP separate and separately identifiable from segregated portfolio assets of any other SP; and

to ensure that assets and liabilities are not transferred between SPs or between an SP and the general assets otherwise than at full value.

Who, historically, has tended to use SPC structures and what would you say one or two of the key benefits are to doing so?

In the investment funds context, SPCs have traditionally been used as a basis for investment platforms on which a Fund Manager can employ varying strategies and use different SPs to hold and segregate assets relating to such strategies (e.g. trading public securities, bonds and other debt instruments, and certain crypto currencies) on the same SPC platform.

The SPC structure is also frequently used for multi-class hedge funds, umbrella funds and master-feeder structures owing to the various benefits of the SPC structure.

What level of activity have you seen among fund managers using SPCs over the last couple of years and have you noticed growing interest among PE/RE managers?

One of the benefits of our firm having a strong investment funds’ practice for clients in the United States and in Asia is that we get to see and to advise on developing trends for offshore funds and the Cayman corporate structures which are preferred for strategies in both geographical markets for funds.

While the SPC structure has been traditionally used in the manner described above, we have seen SPCs being used increasingly in Asia as the preferred structure for private equity funds, real estate funds, and certain other closed-ended funds that allow investors to participate entirely on a deal-by-deal basis.

The more typical approach for structuring a private equity (PE) or real estate (RE) fund in certain other geographical markets (e.g. the US, the UK) is the LP/GP structure where investors invest by acquiring interests in a limited partnership (LP) managed by a general partner (GP) and investors invest on a blind pool basis.

With this approach, the Fund Manager can attract institutional investors who are either not equipped or do not wish to review investments on a deal-by-deal basis and prefer to rely on the expertise of the Fund Manager or GP. Investors are effectively investing in a blind pool fund and do not have any clear indication at the time they make their investment of any of the underlying assets that the Fund will ultimately acquire. Trust is placed by investors on the reputation and ability of the GP or Fund Manager to source and execute unknown deals on terms that will lead to attractive returns over time.

The increasing use in Asia of the SPC structure for PE and RE funds allows the Fund Manager to create one or more SPs in order to segregate the assets and liabilities of each SP from the assets and liabilities of any other SP. The creation of the SP is straightforward and negates a large number of the requirements for setting up an entirely new exempted company for each new transaction to acquire a portfolio asset. These SPC funds appear more likely to attract non-institutional high net worth investors who prefer overseeing each investment decision. The increasing use of the SPC in this way is, among other things, a result of there being less appetite from many non-institutional high net worth investors to invest on a blind pool basis.

What additional considerations or difficulties, if any, do private equity managers face when utilising the SPC structure to cater to investors’ preference for a deal-by-deal approach?

First, with a typical GP/LP structure, GPs and Fund Managers will have some certainty as to how much investor capital is available for any given transaction. With such an SPC structure, which allows investors to invest on a deal-by-deal, the Fund Manager will not have existing contractual commitments from investors, or that can be drawn down at very short notice, and this can affect the ability of the Fund Manager to commit to underlying transactions in a timely manner.

Secondly, the uncertainty of how much investor capital is available, delays caused by investors’ review and decision period and the need for possible joint venture participation can make it difficult for Fund Managers to bid for portfolio acquisition opportunities on time-sensitive transactions.

Thirdly, as all of the capital raised by each SP will often be used to fund the acquisition of the single underlying asset for which the SP was created, the management fees charged on the portfolio asset are often charged up-front at the launch of the SP as a percentage of the aggregate subscription proceeds and often several years’ management fees are charged in advance. This deals with the issue of the SP not having access to cash to make monthly or quarterly management fee payments after acquisition of the portfolio asset.

Fourthly, some of our Fund Manager clients in Asia have used the deal-by-deal SPC fund as a springboard to subsequently launching a larger blind pool fund structured as LP/GP, thereby allowing themselves time to build a track record, build reputation, and importantly meet demands of investors by utilising Cayman fund structures.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) applies to offshore investment funds with European investors since 25 May 2018. The Cayman Islands Data Protection Law (“DPL”), which will regulate the future processing of all personal data, is intended to come into effect in January 20191. Inspired from the UK’s Data Protection Act, DPL includes provisions very similar to GDPR (together “Data Protection Laws”), with certain notable differences.

As part of the subscription process, investors are required to provide a government-issued photo ID, source of funds and wealth, contact details, payment details, and tax residence information, or even additional information about employment, dependents, income and investment objectives (the “Investor Personal Data”), which are processed and stored by or on behalf of the investment fund (the “Fund”) and/or by one or more of the service providers to the Fund. Some of the processing may be done by different parties in various jurisdictions.

Generally, the Administrator, Transfer Agent, Distributor, and the Investment Manager of a Fund may fall within the definition of a Data Controller or Data Processor. To ensure compliance with GDPR and/or DPL, the Fund’s Board of Directors should review the contractual arrangements with these parties and may need to appoint a Data Protection Officer. As a reminder, the Board of Directors of the Fund is required to supervise third party service providers and ensure that there are sufficient measures in place to protect Investor Personal Data. Privacy Notices in the Fund’s offering documents would need to be updated to ensure that investors are fully aware of where their Personal Data is being processed, by whom and for what purpose.

For ease of reference, a brief comparison between GDPR and DPL is included below2.

Comparison of the Main Provisions

| GDPR | DPL | |

| Personal Data | Any information relating to an individual who can be identified, directly or indirectly, from that data (including online identifiers such as IP address-es and cookies may qualify as personal data if they are capable of being linked back to the individual). | Same as GDPR. |

| Data Controller | The person who, alone or with others, determines the purposes, conditions and means of the processing of Personal Data. | DPL applies to any Data Controller in respect of Personal Data (a) es-tablished and processed in the Cayman Islands; or (b) processed in the Cayman Islands otherwise than for the purposes of transit3. |

| Privacy Notice | At the time of collection of the data, individuals must be informed of the purposes and detail behind the processing, the details of transfers of data and any security and technical safeguards in place. This information is generally provided in a separate privacy notice. | Same as GDPR. |

| Right to Access | Individuals have the right to obtain confirmation that their Personal Data is processed and to access it. Data Controllers must respond within a month of the access request. A copy of the information must be provided free of charge. | Same as GDPR, but DPL permits a reasonable fee to be charged. |

| Retention Period | Personal data should not be kept for longer than is necessary to fulfil the purpose for which it was originally collected. Controllers must inform data subjects of the period of time (or reasons why) data will be retained on collection. | Not a requirement under DPL. However, as with the GDPR, if there is no compelling reason for a Data Controller to retain Personal Data, a data subject can request its secure deletion.rsonal data should not be kept for longer than is necessary to fulfil the purpose for which it was originally collected. Controllers must inform data subjects of the period of time (or reasons why) data will be retained on collection. |

| Right to Erase | Should the individual subsequently wish to have their data removed and the Personal Data is no longer required for the reasons for which it was collected, then it must be erased. Data Controllers must notify third party processors or sub-contractors of such requests. | Same as GDPR. |

| Transfers | International transfers permitted to third party processors or between members of the same group. | Same as GDPR. |

| Data Security | Minimum security measures are pre-scribed as pseudonymisation and encryption, ability to restore the availability and access to data, regularly testing, assessing and evaluating security measures. | Appropriate technical and organisational measures must be taken to prevent unauthorised or unlawful processing of Personal Data and against accidental loss or destruction of, or damage to, Personal Data4. |

| Data Processors | Security requirements are extended to data processors as well as Data Controllers. | There is no liability for processors under DPL. However, they may be held liable based on contract or tort law. |

| Data Breach | Data Controllers must notify the regulatory authority of Personal Data breaches without undue delay and, where feasible, not later than 72 hours after having become aware of a breach. | In the event of a Personal Data breach, the Data Controller must, “without undue delay” but no longer than five (5) days after the Data Controller should have been aware of that breach, notify the Om-budsman and any affected individuals5. |

| Breach Notice | The notification should describe the nature of the breach, its conse-quences, the measures proposed or taken by the Data Controller to ad-dress the breach, and the measures recommended by the Data Controller to the individual concerned to miti-gate the possible adverse effects of the breach. | Same as GDPR. |

| Right to be Forgotten | An individual may request the deletion or removal of Personal Data where there is no compelling reason for its continued processing. | DPL contains a similar right, although this is expressed as a general right of “erasure”. Under the UK’s Data Protection Act, the right is limited to processing that causes unwarranted and substantial damage or distress. Under DPL this threshold is not present. As with the GDPR, if there is no compelling reason for a data controller to retain Personal Data, a data subject can request its secure deletion. |

| Right to Object | An individual has the right at any time to require a Data Controller to stop processing their Personal Data for the purposes of direct marketing. There are no exemptions or grounds to refuse. A Data Controller must deal with an objection to processing for direct marketing at any time and free of charge. | Same as GDPR. |

| Direct Marketing and Consent | The Data Controller must inform individuals of their right to object “at the point of first communication” and in a privacy notice. For any consent to be valid it needs to be obvious what the data is going to be used for at the point of data collection and the Data Controller needs to be able to show clearly how consent was gained and when it was obtained. | Including an unsubscribe facility in each marketing communication is recommended best practice. If an individual continues to accept the services of the Data Controller without objection, consent can be implied. |

| Data Processors | The GDPR sets out more detailed statutory requirements to apply to the controller/processor relationship, and to processors in general. Data Pro-cessors are now directly subject to regulation and are prohibited from processing Personal Data except on instructions from the Data Controller. | Best practice would always be to put in place a contract between a controller and processor. Essentially, the contract should require the Data Processor to level-up its policies and procedures for handling personal data to ensure compliance with DPL. Use of sub-contractors by the service provider should be prohibited without the prior approval of the Data Controller6. |

| Data Protection Officer | Mandatory if the core activities of the Data Controller consist of processing operations which require large scale regular and systematic monitoring of individuals or large scale processing of sensitive Personal Data. | Does not require the appointment, although this is recommended best practice. |

| Penalties | Two tiers of sanctions, with maximum fines of up to €20 million or 4% of annual worldwide turnover, whichever is greater. | Refusal to comply or failure to comply with an order issued by the Ombudsman is an offence. Penal-ties are also included for unlawful obtaining or disclosing Personal Data7. Directors may be held liable under certain conditions8.

The Data Controller is liable on conviction to a fine up to CI$100,000 or imprisonment for a term of 5 years or both. Monetary penalty orders of an amount up to CI$250,000 may also be issued against a Data Controller. |

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

E: vivian.huang@loebsmith.com

E: yun.sheng@loebsmith.com

E: elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

- The Data Protection Law, 2017 (Law) was passed on 27 March 2017 and it is not yet in force.

- The comparison only includes provisions which may be relevant to offshore investment funds and is therefore not a comprehensive analysis.

- See Art. 6 of DPL

- See Schedule 1 of DPL

- See Art. 16 of DPL

- Under DPL, the Data Controller is liable for breaches and non-compliance, whereas processors may not be. It is therefore very important for a Fund’s Board of Directors to ensure that adequate contractual protections are in place.

- See Arts. 53-54 of DPL

- See Art. 58 of DPL

Digital Assets. Five Questions to Ask Your Cayman Counsel

In our guidance note Top Ten Best Practices for an ICO Founders’ Team: A View from the Cayman Islands, ICO founder teams and promoters looking at the Cayman Islands for incorporation of their company or companies were warned that, while the Cayman Islands had flexible pragmatic rules encouraging business and innovation, they also had stringent anti-money laundering (“AML”) and know-you-customer (“KYC”) requirements. In addition, other regulatory requirements may be applicable and the company and even its directors and founders may be held liable, under certain circumstances, for any misleading statements made in the White Paper or in additional documentation communicated to token purchasers.

Based on our experience of advising initial coin offerings (ICOs) and security token offerings (STOs) and of undertaking legal due diligence for institutional clients seeking to acquire tokens in ICOs and STOs, in this brief update, we discuss what we view as the five most important questions to discuss with Cayman Islands legal counsel, either prior to setting up, or as soon as possible thereafter, in order (i) to reduce your risk of contravening Cayman Islands law, (ii) to facilitate listing on crypto-exchanges, and (iii) to facilitate better relationships with other participants in the growing digital assets space (e.g. banks to open accounts, institutional investors and investment funds which will undertake due diligence as part of the process of acquiring tokens in an ICO or STO).

1. What are the duties of a Director of a Cayman Islands company?

The constitutional documents of a Cayman Islands company, the Memorandum of Association and the Articles of Association (“Articles”), set out the governance rules and the powers of the Directors. However, the Directors also owe fiduciary duties and certain duties of skill and care under English common law. Among the principal fiduciary duties owed to the Company, the Directors are required to:

i. act, in good faith, in what they consider reasonably to be the best interests of the Company;

ii. exercise their powers under the Articles for the purposes for which those powers are conferred;

iii. avoid conflicts of interests or (where conflicts are permitted by the Articles) ensure that any conflicts are properly disclosed during Board meetings;

iv. exercise their powers independently, without subordinating to the will of others; and

v. not misuse the property of the Company and not make secret profits from their position as a Director.

The Directors should also acquire and maintain a sufficient knowledge of the business on a continuing basis and attend diligently to the affairs of the Company, duties which need to be carried out with reasonable care, diligence and skill. In addition, the Directors also have certain statutory obligations under the Cayman Islands Companies Law (2018 Revision) (the “Companies Law”).

Directors are generally not liable except in cases of negligence, fraud, breach of fiduciary duty, or an action not within their authority which is not ratified by the Company. They may be indemnified by the Company against personal liability for losses incurred arising out of the Company’s business, including in case of negligence and breach of duty (other than breaches of fiduciary duty), except in cases of willful default or fraud.

2. Is there any specific legislation or regulation I should be concerned with?

The Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (“CIMA”) has not issued statements or guidance on virtual currencies, blockchain technology, ICOs or STOs, other than a warning notice dated 23rd April 2018 which specifically flagged a number of risks specifically associated with ICOs and virtual currencies.

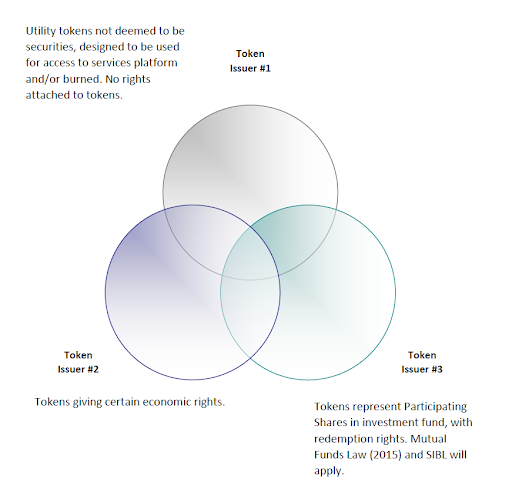

i. The Cayman Islands Securities Investment Business Law (Revised) (“SIBL”) defines securities by reference to a list of instruments, including shares and stock of any kind in the share capital of a company, debentures and any other instruments creating or acknowledging indebtedness other than certain exceptions specified, instruments giving entitlements to securities, certificates conferring rights with respect to securities, etc.

The term “instrument” refers to any record and specifically includes an electronic record as defined in the Electronic Transactions Law (2003 Revision), i.e. a record processed and maintained by electronic means.

Accordingly, CIMA may qualify coins/tokens issued on blockchain as stock or debt if the rights attached to the coins/tokens (as represented in the White Paper or the token sale documentation) resemble rights normally attached to equity interests or debt.

ii. In certain circumstances, a registration with or a license from CIMA may be required:

(a) under the Cayman Islands Money Services Law (Revised), if the coins/tokens issued could give access to money transmission or currency exchange services;

(b) under SIBL, if the coins/tokens may qualify as securities, for all persons engaging, “in the course of business”, in securities investment business, i.e. among other things buying, selling, subscribing for or underwriting securities as agent or principal, arranging deals, managing securities, or advising an investor on buying, selling, underwriting, subscribing for or exercising any right in securities; and/or

(c) under the Mutual Funds Law (2015 Revision) if the issuer of the coins/tokens is essentially a collective investment scheme and the coins/tokens are attached to redemption rights for investors.

3. Should I be concerned by beneficial ownership reporting?

All Cayman Islands companies with certain exceptions such as listed companies, certain companies registered or licensed in the Cayman Islands, companies which are promoted, managed or administered by certain regulated persons, etc. are required to maintain a beneficial ownership register (a “BO Register”) at the registered office.

The BO Register will record details of individuals holding (directly or indirectly):

i. more than 25% of the shares or interests of the company;

ii. more than 25% of voting rights of the company; and/or

iii. the right to appoint or remove a majority of the Board of Directors.

If none of the conditions above are satisfied, an individual will still be a beneficial owner and therefore reportable on the BO Register if he has the absolute and unconditional right to exercise or actually exercises, significant influence or control over the company (other than solely in the capacity of director or manager, professional advisor or professional manager).

4. How do I ensure compliance with the AML regulations?

Token issuers and other companies operating in the digital assets space may be deemed to be undertaking “relevant financial business” in the Cayman Islands, as defined in Schedule 6 of the Proceeds of Crime Law (2018 Revision). The definition includes (but is not limited to):

Acceptance of deposits and other repayable funds from the public.

Lending.

Financial leasing.

Money or value transfer services.

Issuing and managing means of payment (e.g. credit and debit cards, cheques, traveller’s cheques, money orders and bankers’ drafts, electronic money).

Financial guarantees and commitments.

Trading in (a) money market instruments (cheques, bills, certificates of deposit, derivatives etc.); (b) foreign exchange; (c) exchange, interest rate and index instruments; (d) transferable securities; or (e) commodity futures trading.

Participation in securities issues and the provision of financial services related to such issues.

Advice to undertakings on capital structure, industrial strategy and related questions and advice and services relating to mergers and the purchase of undertakings.

Money broking.

Individual and collective portfolio management and advice.

Safekeeping and administration of cash or liquid securities on behalf of other persons.

Safe custody services.

Financial, estate agency, legal and accounting services provided in the course of business relating to (a) the sale, purchase or mortgage of land or interests in land on behalf of clients or customers; (b) management of client money, securities or other assets; (c) management of bank, savings or securities accounts; and (d) the creation, operation or management of legal persons or arrangements, and buying and selling of business entities.

The services of listing agents and broker members of the Cayman Islands Stock Exchange as defined in the CSX Listing Rules and the Cayman Island Stock Exchange Membership Rules respectively.

The conduct of securities investment business.

Dealing in precious metals or precious stones, when engaging in a cash transaction of fifteen thousand dollars or more.

The provision of registered office services to a private trust company by a company that holds a Trust licence under section 6(5)(c) of the Banks and Trust Companies Law (2018 Revision).

Otherwise investing, administering or managing funds or money on behalf of other persons.

Underwriting and placement of life insurance and other investment related insurance.

For a company undertaking relevant financial business, the Proceeds of Crime Law (2018 Revision) and the Anti-Money Laundering Regulations (2018 Revision) of the Cayman Islands (the “AML Regulations”) will apply, and the company will be required to take steps appropriate to the nature and size of their business to identify, assess, and understand its money laundering and terrorist financing risks in relation to a customer, the country or geographic area in which the customer resides or operates, the products, service and transactions, and the delivery channels.

The following AML procedures are required under the AML Regulations currently in force:

i. identification and verification (KYC) procedures for investors/purchasers;

ii. adoption of a risk-based approach to monitor activities;

iii. record-keeping procedures;

iv. procedures to screen employees to ensure high standards when hiring;

v. adequate systems to identify risk in relation to persons, countries and activities which shall include checks against all applicable sanctions lists;

vi. adoption of risk-management procedures concerning the conditions under which a customer may utilize the business relationship prior to verification;

vii. observance of the list of countries, published by any competent authority, which are non-compliant, or do not sufficiently comply with the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF);

viii. internal reporting procedures; and

ix. other procedures of internal control, including an appropriate effective risk-based independent audit function and communication as may be appropriate for the ongoing monitoring of business relationships or one-off transactions for the purpose of forestalling and preventing money laundering and terrorist financing.

For all such companies, the AML Regulations also impose the designation of natural persons, at managerial level, to act as Anti-Money Laundering Compliance Officer (“AMLCO”), Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“MLRO”) and Deputy Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“DMLRO”). CIMA requires that a person acting as MLRO / DMLRO must (i) act autonomously; (ii) be independent (have no vested interest in the underlying activity of the investment fund); and (iii) have access to all relevant material in order to make an assessment as to whether an activity is or is not suspicious. The AMLCO role should be performed by someone at management level, who will be the point of contact with the supervisory and other competent authorities.

CIMA Guidance to the Cayman AML Regulations requires that an AMLCO must be a person who is fit and proper to assume the role and who:

i. has sufficient skills and experience;

ii. reports directly to the Board of Directors (“Board”) or equivalent;

iii. has sufficient seniority and authority so that the Board reacts to and acts upon any recommendations made;

iv. has regular contact with the Board so that the Board is able to satisfy itself that statutory obligations are being met and that sufficiently robust measures are being taken to protect the Fund against money laundering/terrorist financing risks;

v. has sufficient resources, including sufficient time and, where appropriate, support staff; and

vi. has unfettered access to all business lines, support departments and information necessary to appropriately perform the AML/CFT compliance function.

CIMA has the power to impose fines for non-compliance on entities and individuals who are subject to the AML Regulations, starting from approximately US$6,000 for a minor breach to fines of US$61,000 (for an individual) or US$122,000 (for an entity). For a breach prescribed as very serious, the fines may reach approximately US$122,000 (for an individual) and approximately US$1,220,000 (for an entity). If a breach is also a criminal offence, the imposition by CIMA of a fine will not preclude separate prosecution for that offence (or be limited by the penalty stipulated for that offence).

5. How do I limit my risks?

Beyond discussing with your counsel and understanding what are the continuing obligations of a Cayman Islands company, the duties of a Director, the applicable laws and required AML compliance, it is essential that token issuers and other companies operating in the digital assets space be aware of the solutions they may have under Cayman Islands laws for mitigating their risk exposure, such as indemnification agreements, specific provisions to be included in the Memorandum and Articles of Association, risk factors to be disclosed and other disclaimers, specific dispute resolution mechanisms, etc.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or either:

E ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

E elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

Introduction

The Anti-Money Laundering Regulations (2018 Revision) of the Cayman Islands (AML Regulations), have expanded the scope of Cayman Islands anti-money laundering regime (“AML”) significantly, including its application to investment funds generally, and specifically to (i) private equity funds and other closed-ended funds (e.g. venture capital and real estate funds) which are not registered with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (“CIMA“).

The AML Regulations have introduced a new risk-based approach to AML in the Cayman Islands, including requiring persons subject to the AML Regulations including Cayman Islands investment funds to take steps appropriate to the nature and size of their business to identify, assess, and understand its money laundering and terrorist financing risks in relation to each investor, the country or geographic area in which each investor resides or operates, the types of individuals/entities that make up the investor base of the investment fund, source of funds (e.g. investment funds with lower minimum investment thresholds might pose a greater risk of money laundering, especially if the subscription proceeds are not coming from a regulated financial institution), and redemption terms.

Going forward all non-CIMA registered and unregulated investment funds will be required to comply with the same AML regime as CIMA registered and regulated funds.

Designated AML Officer Roles

Pursuant to regulations 3(1) and 33 of the AML Regulations, a Cayman domiciled investment fund must designate a natural person, at managerial level, to act as its Anti-Money Laundering Compliance Officer (“AMLCO”), Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“MLRO”) and Deputy Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“DMLRO”). CIMA requires that a person acting as MLRO / DMLRO must (i) act autonomously; (ii) be independent (have no vested interest in the underlying activity of the investment fund); and (iii) have access to all relevant material in order to make an assessment as to whether an activity is or is not suspicious. The AMLCO role should be performed by someone at management level, who will be the point of contact with the supervisory and other competent authorities.

CIMA Guidance to the AML Regulations requires that an AMLCO must be a person who is fit and proper to assume the role and who:

i. has sufficient skills and experience;

ii. reports directly to the Board of Directors (“Board”) or equivalent;

iii. has sufficient seniority and authority so that the Board reacts to and acts upon any recommendations made;

iv. has regular contact with the Board so that the Board is able to satisfy itself that statutory obligations are being met and that sufficiently robust measures are being taken to protect the Fund against money laundering/terrorist financing risks;

v. has sufficient resources, including sufficient time and, where appropriate, support staff; and

vi. has unfettered access to all business lines, support departments and information necessary to appropriately perform the AML/CFT compliance function.

Expanded AML Procedures

In addition to having the AMLCO, MLRO, and DMLRO officers in place, investment funds are required to have the following AML procedures in place:

-

- identification and verification (KYC) procedures for its investors/clients;

- adoption of a risk-based approach to monitor financial activities;

- record-keeping procedures;

- procedures to screen employees to ensure high standards when hiring;

- adequate systems to identify risk in relation to persons, countries and activities which shall include checks against all applicable sanctions lists;

- adoption of risk-management procedures concerning the conditions under which a customer may utilize the business relationship prior to verification;

- observance of the list of countries, published by any competent authority, which are non-compliant, or do not sufficiently comply with the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force;

- internal reporting procedures (involving the MLRO and DMLRO); and

- such other procedures of internal control, including an appropriate effective risk-based independent audit function and communication as may be appropriate for the ongoing monitoring of business relationships or one-off transactions for the purpose of forestalling and preventing money laundering and terrorist financing.

When will the new changes apply to non-CIMA registered and unregulated investment funds?

In order to allow non-CIMA registered unregulated investment entities (e.g. closed-ended funds such most private equity funds, venture capital funds, and real estate funds) not previously subject to the AML regime time to implement appropriate procedures (or delegation arrangements) to be in compliance with the new AML regime, the AML Regulations have been amended to provide these entities up until 31 May 2018 to assess their existing AML/CTF procedures and to implement policies and procedures which are in compliance with the AML Regulations.

The deadline to designate an AMLCO, MLRO, and DMLRO and to notify CIMA of the identity of such persons holding these roles is on or before 30 September 2018 for existing funds.

What do managers of Cayman Funds need to be aware of, in particular those managing funds not previously registered with CIMA?

A Cayman Fund that is already registered with and regulated by CIMA will typically have delegated the maintenance of AML procedures on behalf of the Fund to a Fund Administrator, and should therefore check that the scope of its current delegation to its Administrator is sufficiently broad to cover the requirements of the AML Regulations (e.g. check (i) whether the AML regime being applied in respect of the Fund is the Cayman AML regime or the regime of jurisdiction recognized as having an equivalent AML regime, and (ii) if it is the latter, whether or not the relevant Administrator is actually subject to the AML regime of that jurisdiction1).

Non-CIMA registered investment funds which now fall under the new AML regime and which have delegated maintenance of AML procedures on behalf of the Fund to a Fund Administrator should also check that the scope of delegation to its Administrator or investment manager is sufficiently broad to cover the requirements of the AML Regulations. Investment entities which have not appointed a Fund Administrator (e.g. because the investment manager maintains the AML procedures on the Fund’s behalf) should check the same matters outlined above and additionally, whether or not the delegate (e.g. the investment manager) has the requisite personnel (in terms of numbers, training, and experience) to maintain the AML procedures on the Fund’s behalf. The extent to which (i) the maintenance of AML procedures on behalf of the Fund, and (ii) the designation of AMLCO, MLRO, and DMLRO functions, can be delegated to a third party service provider should also be considered within the context of CIMA’s guidance on outsourcing.

Enforcement

The Monetary Authority Law (2018 Revision) gives CIMA the power to impose administrative fines for non-compliance on entities and individuals who are subject to Cayman Islands regulatory laws and/or the AML Regulations.

For a breach prescribed as minor fine would be CI$5,000 (approximately US$6,000). For a breach prescribed as minor the Authority also has the power to impose one or more continuing fines of CI$5,000 each for a fine already imposed for the breach (the “initial fine”) at intervals it decides, until the earliest of the following to happen:

(a) the breach stops or is remedied;

(b) payment of the initial fine and all continuing fines imposed for the breach; or

(c) the total of the initial fine and all continuing fines for the breach reaches CI$20,000 (approximately US$24,000).For a breach prescribed as serious, the fine is a single fine not exceeding: (a) CI$50,000 (approximately US$61,000) for an individual; or (b) $100,000 (approximately US$122,000) for a body coporate.

For a breach prescribed as very serious, the fine is a single fine of not exceeding: (a) CI$100,000 (US$122,000) for an individual; or (b) CI$1,000,000 (US$1,220,000) for a body corporate.

For specific advice on the Cayman Islands’ Anti-Money Laundering Regulations, please contact any of:

E gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

E yun.sheng@loebsmith.com

1. Sections 3.61 and 3.62 of the CIMA Guidance on AML/CTF makes it clear that where a Cayman investment entity delegates AML/CTF compliance procedures to a delegate and that delegate is located in a jurisdiction with an equivalent AML/CTF and is subject to the anti-money laundering regime of that jurisdiction, CIMA will regard compliance with the regulations of such jurisdictions as compliance with the AML Regulations and Guidance Notes.

Voluntary liquidations generally

As the conclusion of 2018 approaches, clients should give some thought to whether or not they have Cayman entities which they wish to liquidate prior to the end of 2018 for, among other things, the purpose of avoiding annual government registration fees due in January 2019. A voluntary liquidator of a Cayman company or exempted limited partnership (ELP) is required to hold the final general meeting for that company or file the final dissolution notice for that ELP on or before 31 January 2019.

Voluntary liquidations – Funds registered with CIMA

Investment Funds which are registered with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) should commence voluntary liquidation and submit documents to CIMA in order to have those Funds’ status change from “active” to “license under liquidation” by Monday, 31 December 2018 if they are to avoid their annual fees payable to CIMA for 2019. It is also important for investment funds registered with CIMA to give some thought to CIMA’s requirement for a final “stub” audit for the period of 2018 in respect of which the Fund operated before going into liquidation. CIMA may be reluctant to grant a partial year audit waiver for a liquidating Fund.

As an alternative to voluntary liquidation, some investment fund managers might be considering a wind down of one or more CIMA registered funds prior to the end 2018 and wish to de-register from CIMA or at least go into the status of “licence under termination” with CIMA in order to avoid or reduce annual registration fees payable to CIMA for 2019. If not already started, we recommend that action be taken now to begin this process.

For specific advice on voluntary liquidation of Cayman Islands’ entities or winding down in-vestment funds before 31 December 2018, please contact any of:

E gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

E yun.sheng@loebsmith.com

E vivian.huang@loebsmith.com

E elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

The Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (“CIMA”) has extended the deadline for each CIMA registered Cayman domiciled investment fund which launched prior to 1 June 2018 to notify CIMA of the appointment of natural persons to act as its Anti-Money Laundering Compliance Officer (“AMLCO”), Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“MLRO”) and Deputy Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“DMLRO”) from 30 September 2018 to 31 December 2018. CIMA has clarified that CIMA regulated funds must still appoint these AML Officers by 30 September 2018 but now have until 31 December 2018 to notify CIMA of such appointments. Notification of the appointment of AML Officers to CIMA registered funds must take place via the CIMA REEFS portal.

CIMA has also clarified that each unregulated Cayman investment fund (and is therefore not registered with CIMA) which launched prior to 1 June 2018 now has until 31 December 2018 to designate entity specific AML Officers. Each Cayman investment fund launched from 1 June 2018 (“Post May 2018 Funds”) are expected to have AML Officers designated from the time of launch. Post May 2018 Funds which are required to register with CIMA will be required to register details of their AML Officers at the time of the fund’s registration with CIMA.

For specific advice on the appointment of AML Officers to your Cayman Islands’ investment funds, please contact any of:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: vivian.huang@loebsmith.com

E ramona.tudorancea@loebsmith.com

E elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

The AML Revision

The Anti-Money Laundering Regulations (2018 Revision) of the Cayman Islands (AML Regulations) have expanded the scope of the Cayman Islands’ anti-money laundering regime significantly, including its application to investment funds generally, and specifically to (i) private equity funds and other closed-ended funds (e.g. venture capital and real estate funds) which are not registered with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (Cima).

The AML Regulations have introduced a new risk-based approach to AML in the Cayman Islands, including requiring persons subject to the AML Regulations (which include Cayman Islands investment funds) to take steps appropriate to the nature and size of their business to identify, assess, and understand its money laundering and terrorist financing risks in relation to each investor, the country or geographic area in which each investor resides or operates, the types of individuals/entities that make up the investor base of the investment fund, source of funds (e.g. investment funds with lower minimum investment thresholds might pose a greater risk of money laundering, especially if the subscription proceeds are not coming from a regulated financial institution), and redemption terms.

APPLICATION OF THE NEW AML REGIME

The scope of the AML Regulations is still defined by reference to “relevant financial business”. Persons undertaking relevant financial business in the Cayman Islands must comply with the requirements of the AML Regulations. The definition of relevant financial business that was included in previous versions of the anti-money laundering regulations has been removed from the AML Regulations and has instead been placed in Section 2 of the Proceeds of Crime Law (2018 Revision) (PCL). The definition continues to cover “mutual fund administration or the business of a regulated mutual fund within the meaning of the Mutual Funds Law (2015 Revision)” which covers all funds registered with and regulated by Cima. The definition had also covered and continues to cover investment managers licensed by or registered with Cima (e.g. those who have applied for and obtained status as an “excluded person” under the Securities Investment Business Law for an exemption from the requirement for a licence).

However, Section 2 and Schedule 6 of the PCL now extends the meaning of “relevant financial business” to cover activities which are “otherwise investing, administering or managing funds or money on behalf of other persons”.

The net effect of expanding the meaning of “relevant financial business” to include activities of investing, administering or managing funds or money on behalf of other persons is that now all unregulated investment entities are also covered and will need to maintain AML procedures in accordance with the AML Regulations.

EXPANDED AML PROCEDURES

Going forward, all non-Cima-registered and unregulated investment funds will also be required to comply with the same AML regime as Cima registered and regulated funds.

Pursuant to regulations 3(1) and 33 of the AML Regulations, an investment fund doing business in or from the Cayman Islands must designate a natural person, at managerial level, to act as its anti-money laundering compliance officer (AMLCO), money laundering reporting officer (MLRO) and deputy money laundering reporting officer (DMLRO). Cima requires that a person acting as MLRO/ DMLRO must (i) act autonomously; (ii) be independent (have no vested interest in the underlying activity of the investment fund); and (iii) have access to all relevant material in order to make an assessment as to whether an activity is or is not suspicious. The AMLCO role should be performed by someone who will be the point of contact with the supervisory and other competent authorities.

CIMA guidance to the AML Regulations requires that an AMLCO must be a person who is fit and proper to assume the role and who:

- has sufficient skills and experience;

- reports directly to the board of directors of the fund or equivalent;

- has sufficient seniority and authority so that the boardreacts to and acts upon any recommendations made;

- has regular contact with the board so that the board is able to satisfy itself that statutory obligations are being met and that sufficiently robust measures are being taken to protect the fund against money laundering/terrorist financing risks;

- has sufficient resources, including sufficient time and, where appropriate, support staff; and

- has unfettered access to all business lines, support departments and information necessary to appropriately perform the AML/CFT compliance function.

In addition to having the AMLCO, MLRO, and DMLRO officers in place, investment funds are required to have following AML procedures in place:

- identification and verification (KYC) procedures for its investors/clients;

- adoption of a risk-based approach to monitor financial activities;

- record-keeping procedures ;

- procedures to screen employees to ensure high standards when hiring;

- adequate systems to identify risk in relation to persons, countries and activities which shall include checks against all applicable sanctions lists;

- adoption of risk-management procedures concerning the conditions under which a customer may utilise the business relationship prior to verification;

- observance of the list of countries, published by any competent authority, which are non-compliant, or do not sufficiently comply with the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force;

- internal reporting procedures (involving the MLRO and DMLRO); and

- such other procedures of internal control, including an appropriate effective risk-based independent audit function and communication as may be appropriate for the ongoing monitoring of business relationships or one-off transactions for the purpose of forestalling and preventing money laundering and terrorist financing.

NEW CHANGES

In order to allow non-Cima registered unregulated investment entities (e.g. closed-ended funds such most private equity funds, venture capital funds, and real estate funds) not previously subject to the AML regime time to implement appropriate procedures (or delegation arrangements) to be in compliance with the new AML regime, the AML Regulations have been amended to provide these entities up until 31 May 2018 to assess their existing AML/ CTF procedures and to implement policies and procedures which are in compliance with the AML Regulations.

The deadline to designate an AMLCO, MLRO, and DMLRO and to notify Cima of the identity of such persons holding these roles is on or before 30 September 2018 for existing funds.

MANAGERS SHOULD BE AWARE

A Cayman fund that is already registered with and regulated by Cima will typically have delegated the maintenance of AML procedures on behalf of the fund to a fund administrator, and should therefore check that the scope of its current delegation to its administrator is sufficiently broad to cover the requirements of the AML Regulations (e.g. check (i) whether the AML regime being applied in respect of the fund is the Cayman AML regime or the regime of jurisdiction recognised as having an equivalent AML regime, and (ii) if it is the latter, whether or not the relevant administrator is actually subject to the AML regime of that jurisdiction ).

Non-CIMA-registered investment funds which now fall under the new AML regime and which have delegated maintenance of AML procedures on behalf of the fund to a fund administrator should also check that the scope of delegation to its administrator or investment manager is sufficiently broad to cover the requirements of the AML Regulations. Investment entities which have not appointed a fund administrator (e.g. because the investment manager maintains the AML procedures on the fund’s behalf) should check the same matters outlined above and additionally, whether or not the delegate (e.g. the investment manager) has the requisite personnel (in terms of numbers, training, and experience) to maintain the AML procedures on the fund’s behalf. The extent to which (i) the maintenance of AML procedures on behalf of the fund, and (ii) the designation of AMLCO, MLRO, and DMLRO functions, has been or is to be delegated to a third party service provider should also be considered within the context of Cima’s guidance on outsourcing.

ENFORCEMENT

The Monetary Authority Law (2018 Revision) gives Cima the power to impose administrative fines for non-compliance on entities and individuals who are subject to Cayman Islands regulatory laws and/or the AML Regulations.

For a breach prescribed as minor fine would be KYD5,000 (approximately US$6,000). For a breach prescribed as minor, Cima also has the power to impose one or more continuing fines of KYD5,000 each for a fine already imposed for the breach (the “initial fine”) at intervals it decides, until the earliest of the following to happen:

(a) the breach stops or is remedied;

(b) payment of the initial fine and all continuing fines imposed for the breach; or

(c) the total of the initial fine and all continuing fines for the breach reaches KYD20,000.

For a breach prescribed as serious, the fine is a single fine not exceeding: (a) KYD50,000 for an individual; or (b) KYD100,000 for a body corporate. For a breach prescribed as very serious, the fine is a single fine of not exceeding: (a) KYD100,000 for an individual; or (b) KYD1m for a body corporate.

Gary Smith

Gary Smith is a partner in the corporate and investment funds group at Loeb Smith Attorneys. He is an expert on Cayman Islands investment funds law and has given expert evidence in the US Federal Bankruptcy court relating to Cayman investment funds. He is also author of many legal articles including: US Court and Cayman Islands Court: Sharing Jurisdiction in the Interests of Comity, published in International Corporate Rescue Vol.12 (2015) Issue 1; and Fiduciary duties of a general partner of a Cayman exempted limited partnership published in Practical Law Global Guide 2015/16 – Private Equity and Venture Capital.

E gary.smith@loebsmith.com

W www.loebsmith.com

The Cayman Islands has been the leading offshore jurisdiction for M&A activity over the last few years, with a steady flow of over US $77 billion in combined value of target companies for 2016 and 2017, and a peak of over US $115 billion in 2015. By way of comparison, in 2017, the combined value of transactions targeting companies incorporated in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and Hong Kong was US $37 billion and US $40 billion respectively (Global M&A Review 2017 report published by Bureau van Dijk).

A significant portion of the M&A activity was related to merger take-privates (that is, transactions involving a group of investors purchasing all outstanding shares of a company’s stock and returning it to a privately held company) of Cayman-incorporated companies listed on the US stock exchanges, which were achieved through the Cayman Islands statutory merger regime (Cayman Merger Law). The related transactions also generated a high volume of litigation in the Cayman Islands, as any shareholder who is unhappy with the consideration offered as part of a merger can dissent and is entitled to payment of fair value of its shares under section 238 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law (2018 Revision) (Companies Law). The fair value, if not agreed between the parties, is determined by the Grand Court of the Cayman Islands.

This article aims to review some of the major case law developments in 2017 in the context of the Cayman Merger Law and its use in merger take-private transactions of Cayman companies from international stock exchanges (for example, NYSE, NASDAQ, HKSE) as well as how these developments will affect the approach taken by dissenting shareholders in future merger take-private transactions for Cayman companies.

Ability of dissenting shareholders to seek interim payments

Under the Grand Court Rules, interim payments can be requested by dissenting shareholders and granted by the Grand Court during the judicial proceedings initiated to determine the “fair value” of the dissenters’ shares under Section 238 of the Cayman Merger Law (Blackwell Partners LLC et al v Qihoo 360 Technology Co Ltd, interim judgement of 26 January 2017). This decision brought a significant development for minority shareholders in their quest to obtain the “fair value” for their shares in the context of a merger take-private.

Typical minority shareholder strategies

Diligent minority shareholders typically learn of a merger take-private offer within days of the first press release by the company which announces the receipt of an offer by the board of directors and the formation of a special committee of independent directors (Special Committee) to review the offer and negotiate on behalf of the company. At this point several strategies become available:

- Activism and raising concerns. Minority shareholders may look towards activist shareholders or take a more active role themselves, either writing to the board of the company and/or communicating to the other shareholders through public media. Any concerns that the minority shareholders may have about the proposed merger should be raised at this stage. These may include (among others):

-

- the merger not being in the best interest of the company;

- the consideration being below the company’s intrinsic value taking account of the company’s market share;

- the company’s market position;

- specialist technologies;

- the accumulated cash position; or

- the holding of trading licenses relating to certain specialist areas or assets.

- Ideally, these concerns should be raised sufficiently early before any determination by the board of the company regarding the approval of the offer and recommendation to company’s shareholders, and the execution of the merger agreement. The aim of this approach is to ensure that the Special Committee will properly review the offer and obtain:

-

- in-depth information about the valuation of company and the proposed financing and structuring of the merger, that may lead to an increase of the merger consideration negotiated by the Special Committee for the benefit of all shareholders; and/or

-

- additional protections to benefit minority shareholders, such as “majority of minority” provisions in the merger agreement to secure a better bargaining position for minority shareholders leading to the shareholders’ meeting convened to approve the merger and the terms of the merger agreement.

- Looking for alternatives. If the target company received an offer from the management group or a group composed of the management and certain private equity sponsors (the buyout group), activist shareholders may try to look for an alternative buyer, generally inviting third party interest, or associate with other sponsors to initiate a counter-offer. This strategy is based on the assumption that the Special Committee will be bound by its fiduciary duties to take into consideration any additional offers received, which may place upward pressures on the initial merger consideration proposed by the buyout group. However, the effectiveness of this strategy is generally limited by the following factors:

-

- if the buyout group, including the management team of the target company (generally in control of a significant number of votes), in the initial offer, clearly states that they do not intend to sell their shares in any alternative transaction, the interest of any third-party buyer is greatly diminished (an alternative offer may be deemed “hostile” by the management team of the target company, and the third party purchaser may invest significant time and money in the proposal with very limited chances of success); and

-

- the Special Committee will not be able to pursue an alternative offer which lacks substance (that is, merger terms, financing, legal documentation, and so on) other than as a simple manifestation of interest.

- Blocking completion. Minority shareholders may seek to file for an injunction to stay or stop the progress of the merger on the basis that the directors of the target company are acting in breach of their fiduciary duties. This strategy is based on the fact that most merger agreements include, as one of the conditions to the closing of the merger, that no final order by a court or other governmental entity will be in effect that prohibits the consummation of the merger or that makes the consummation of the merger illegal. As such, if minority shareholders are successful in obtaining an injunction and such injunction has not been reversed and is non-appealable, then the merger cannot become effective. In some cases, however, the aim of this strategy is not to block the merger but to engage in settlement discussions with the target company and/or the buyout group.

- Exercising dissenters’ rights. Minority shareholders may choose to dissent to the merger under section 238 of the Companies Law, knowing that the target company must negotiate first and must file a petition with the court for judicial determination of the “fair value” amount to be paid (in the absence of an agreement with the dissenting shareholders as to the “fair value” of the shares). In some cases, the merger agreement may include a condition, as one of the conditions to the closing of the merger, that dissenting shareholders do not own more than a certain percentage (usually in the range of 1% to 5%) of the shares of the target company. When coupled with activism by dissenting shareholders, these clauses may put significant pressure on the buyout group and the management team of the target company.

Information can also be disclosed during court proceedings for a judicial determination of the “fair value” that could later lead to a securities class action in a US court or other jurisdiction where the target company was listed.

Significance of the ruling in Blackwell Partners v Qihoo

The interim judgement issued in Blackwell Partners LLC et al v Qihoo 360 Technology Co Ltd became very significant in the context of minority shareholders deciding whether to exercise their dissenting rights under section 238 of the Companies Law.

New interim payment relief

The judgment in the Blackwell Partners v Qihoo case has opened the door to petitions for interim payment being filed systematically by dissenting shareholders as part of the section 238 proceedings, at least in the amount of the merger consideration which is offered generally to the shareholders. This could potentially change the balance of power to some extent in the negotiations between the target company and the dissenting shareholders, possibly encouraging settlement earlier in the process or for higher amounts.

Agreement on security deposit

The security payment made to the court by the target company in the Blackwell Partners v Qihoo case was over five times the amount previously offered to the dissenting shareholders as “fair value”, and likely contributed to the decision of the court to grant an interim payment to the dissenting shareholders. However, it is possible that the absence of an agreement as to a security deposit paid into court would not prevent the court from granting interim payments.

The Grand Court Rules clearly state that the court retains full discretion with respect to interim payments and can order the defendant to make an interim payment of any amount the court thinks just, after considering any set-off, cross-claim or counterclaim on which the defendant may be entitled to rely (O 29, r 12, Grand Court Rules).

Amount of interim payments

It seems unlikely that any interim payments ordered as part of Section 238 proceedings will exceed the merger consideration approved as part of the merger agreement. However, Blackwell Partners v Qihoo does not expressly preclude the possibility of relying on expert evidence to determine that the “just” amount for an interim payment should exceed the merger consideration.

Overall, it is still too early to tell the extent to which Blackwell Partners v Qihoo has or will impact dissenting shareholder strategies in the context of merger take-privates, and possibly contribute to the rising number of section 238 petitions in the Cayman Islands.

Building blocks of the dissenters’ rights to interim relief