About Loeb Smith

People

Sectors

Expertise

- Legal Service

- Banking and Finance

- Blockchain, Fintech and Cryptocurrency

- Capital Markets and Privatization

- Corporate

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy

- Insolvency, Restructuring and Corporate Recovery

- Insurance and Reinsurance

- Intellectual Property

- Investment Funds

- Litigation and Dispute Resolution

- Mergers and Acquisitions

- Private Client and Family Office

- Private Equity and Venture Capital

- Governance, Regulatory and Compliance

- Entity Formation and Managed Services

- Consulting

- Legal Service

News and Announcements

Locations

Subscribe Newsletters

Contact

Cayman Islands exempted companies are widely utilized in structuring cross-border finance transactions. One of the key reasons for this is that the Cayman Islands provides a flexible and well-tested regime for secured financing transactions that is attractive to borrowers and lenders alike.

In this brief guide, we address certain of the key Cayman Islands law points pertaining to the enforcement of an equitable mortgage over shares (the “Secured Shares”) in a Cayman Islands exempted company (the “Secured Company”). An equitable mortgage is the most popular form of security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company.

For details regarding the creation and protection of security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company, please refer to our guide entitled “Granting and protecting security over shares in a Cayman Islands exempted company”.

1. Security deliverables and power of attorney

The terms of a well-drafted Cayman Islands law governed security document with respect to Secured Shares in a Secured Company and the principal finance document will usually require the security provider to deliver the following documents to the secured party to assist with an enforcement:

i. any original share certificate(s) with respect to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company;

ii. an undated share transfer form with respect to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company – the secured party may date this and insert details of the transferee in an enforcement for the purposes of transferring the Secured Shares to itself or a nominee;

iii. an undated resignation letter from each director of the Secured Company – the secured party may date these in an enforcement for the purposes of removing the existing directors of the Secured Company;

iv. a letter of authorization from each director of the Secured Company authorizing the secured party to date each undated letter of resignation upon the occurrence of a default under the security document;

v. an irrevocable proxy with respect to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company in favor of the secured party – this can assist the secured party in taking control of the Secured Company before a transfer of Secured Shares in the Secured Company has been completed;

vi. a letter of instruction to the Secured Company’s registered office service provider containing, among other things, directions to register a transfer of Secured Shares in the Secured Company upon the occurrence of a default under the security document;

vii. a letter of acknowledgement from the registered office service provider with respect to the instructions contained in the letter of instruction;

viii. if the security provider is a Cayman Islands exempted company, a certified copy of its register of mortgages and charges showing the security created over the Secured Shares in the Secured Company – refer to our guide entitled “Granting and protecting security over shares in a Cayman Islands exempted company” for further details;

ix. a certified copy of the Secured Company’s register of members annotated to show the security created over the Secured Shares in the Secured Company (if commercially agreed) – refer to our guide entitled “Granting and protecting security over shares in a Cayman Islands exempted company” for further details;

x. if the security provider is a Cayman Islands exempted company, a copy of the board resolutions of its board of directors authorizing:

a. its entry into and execution of the security document; and

b. the updates to its register of mortgages and charges;

xi. a copy of the board resolutions of the Secured Company authorizing:

a. its entry into and execution of the security document (if it is a party);

b. its register of members to be annotated (if commercially agreed); and

c. a transfer of Secured Shares upon the occurrence of a default under the security document; and

xii. a special resolution passed by the Secured Company with respect to certain changes to its memorandum of association and articles of association (the “M&A”), if required – refer to our guide entitled “Granting and protecting security over shares in a Cayman Islands exempted company” for further details.

A well-drafted share mortgage will include an irrevocable power of attorney granted by the security provider in favor of the secured party enabling it to date and complete the share transfer form in respect of the Secured Shares in the Secured Company and the other documents requiring completion on enforcement.

2. Enforcement rights and remedies

Cayman Islands law permits security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company to be governed by Cayman Islands law or foreign law. One advantage of adopting a foreign governing law clause in a security document is that it may make available certain additional remedies (such as appropriation) which are not available under Cayman Islands law.

Cayman Islands law governed equitable share mortgage

Power of sale

A secured party will usually acquire a power of sale:

i. as a matter of common law; and

ii. as a matter of contract pursuant to the terms of the security document.

It is not necessary to obtain a court order to exercise the power of sale, though it may be preferable to do so in certain circumstances. For example, if the secured party wishes to buy the Secured Shares in a Secured Company or sell them to a third party in a depressed market, a court order may protect the secured party from a claim that it did not receive the best price reasonably obtainable.

Receivership

A secured party will acquire the right to appoint a receiver as a matter of contract pursuant to the terms of any well-drafted security document. This is the most common method of enforcing share security and is an out of court procedure.

Once a receiver has been appointed, it can vote and sell the Secured Shares in the relevant Secured Company, as well as receive any distributions from the Secured Shares. A receiver will usually remove the Secured Company’s existing directors once appointed and liquidate the Secured Company’s underlying assets to facilitate repayment of the debt.

Taking possession

The secured party may also take possession of the Secured Shares in a Secured Company by becoming registered as the legal owner of the Secured Shares. It can do this by dating and completing the share transfer form and presenting it to the Secured Company’s registered office service provider for the purposes of updating the Secured Company’s register of members. It can then also exercise any shareholder rights that become available.

Foreclosure

If the secured party acquires legal title to the Secured Shares in a Secured Company, it also has a right of foreclosure. This remedy extinguishes the security provider’s legal and beneficial title to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company but not its obligation to pay any secured and unpaid sums. Foreclosure involves a time-consuming and costly court process and is not usually exercised in practice given its draconian nature.

Foreign law governed share security document

Where the security document is governed by foreign law, the:

i. security document should comply with the requirements of its governing law to be valid and binding; and

ii. remedies available to a secured party are governed by the governing law and the terms of the security document.

3. Application of proceeds of enforcement

Subject to any provisions to the contrary in the security document, all amounts that accrue from the enforcement of the security document are applied in the following order of priority:

i. firstly, in paying the costs incurred in enforcing the security document;

ii. secondly, in discharging the sums secured by the security document;

iii. and thirdly, in paying any balance due to the security provider.

4. Stop notices

If the secured party has concerns that the security provider may transfer the Secured Shares in the relevant Secured Company to a third party or pay a distribution with respect to them in breach of the terms of the security document before any enforcement action has been completed, it may be possible to obtain a stop notice.

A stop notice does not require a court hearing and is obtained from the Registrar of the Grand Court (the “Registrar of the Court”). Upon a successful application, the Registrar of the Court issues a stop notice requiring 14 days’ notice to be given to the secured party before any transfer of Secured Shares in the relevant Secured Company or any payment of a distribution with respect to them can occur.

5. Rectification of the register of members

To the extent that the registered office service provider of a Secured Company is uncooperative in updating the register of members of that Secured Company to reflect a transfer of Secured Shares, the secured party may apply to court to rectify the register on the grounds that there has been an unnecessary delay in entering it as a new shareholder.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact:

Peter Vas

Partner

Loeb Smith Attorneys

Hong Kong

T: +852 5225 4920

E: peter.vas@loebsmith.com

Cayman Islands exempted companies are widely utilized in structuring cross-border finance transactions. One of the key reasons for this is that the Cayman Islands provides a flexible and well-tested regime for secured financing transactions that is attractive to borrowers and lenders alike. The process for creating security in the Cayman Islands is also straightforward and will not typically impact the timeframe of a proposed transaction.

In this brief guide, we address certain of the key Cayman Islands law points pertaining to the creation and protection of security over shares (the “Secured Shares”) in a Cayman Islands exempted company (the “Secured Company”).

1. Creation of security

The Companies Act (as Revised) of the Cayman Islands (the “Act”) does not contain any provisions with respect to the creation of security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company. Therefore, the security should adhere to the following principles derived from common law:

it must be in writing;

- the security document must be signed by,

- or with the authority of, the security provider; and

- the security document must clearly indicate the intention to create security over the Secured Shares and the amount secured or how that amount is to be calculated.

Cayman Islands law recognizes various forms of security over assets, including equitable mortgages and charges which are most commonly taken over Secured Shares in a Secured Company.

2. Execution formalities and regulatory approvals

Cayman Islands law does not prescribe a particular mode of execution with respect to security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company and it is not necessary for such security to be certified, notarized or apostilled to make the security valid or enforceable from a Cayman Islands law perspective. That being said, in practice, a security document with respect to Secured Shares in a Secured Company is customarily executed as a deed.

From an execution standpoint, it is important to review the memorandum of association and articles of association (the “M&A”) of the relevant security provider and the relevant Secured Company, to the extent it is a party to the security document, to ensure compliance with any applicable signing formalities.

Unless security is being taken in a Secured Company which is a “regulated person”, such as a bank or a mutual fund, no regulatory approvals are necessary to create valid and enforceable security as a matter of Cayman Islands law.

3. Stamp duty and taxes

No stamp duty or taxes are payable with respect to the creation of security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company or upon any transfer thereof in an enforcement as a matter of Cayman Islands law so long as:

- the security document and any ancillary documents thereunder are not executed or delivered in, brought into, or produced before a court of, the Cayman Islands; and/or

- the Secured Company does not have an interest in land in the Cayman Islands, or shares in a subsidiary that has an interest in land in the Cayman Islands.

4. Governing law of the security

Cayman Islands law permits security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company to be governed by Cayman Islands law or foreign law.

In cross-border finance transactions, it is relatively common for the governing law of a security document over Secured Shares in a Secured Company to be aligned with the governing law of the principal finance documents. One advantage of adopting a foreign governing law clause in a security document is that it may make available certain additional remedies (such as appropriation) which are not available under Cayman Islands law. Care should however be taken to ensure that there are no conflicts of law issues where a security document is governed by foreign law. English, Hong Kong and Singapore law are frequently adopted to govern security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company and no major conflicts of law issues are likely to arise.

Cayman Islands law governed security document

Where the security document is governed by Cayman Islands law, so long as it is in customary form, the secured party is entitled to the following remedies in the event of a default:

- the right to take possession of the Secured Shares in the Secured Company (subject to redemption by the security provider upon the settlement of the debt);

- the right to sell the Secured Shares in the Secured Company; and

- the right to appoint a receiver who may:

-

- vote the Secured Shares in the Secured Company;

- receive distributions in respect of the Secured Shares in the Secured Company; and

- exercise other rights and powers of the security provider in respect of the Secured Shares in the Secured Company.

If the secured party acquires legal title to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company, it also has a right of foreclosure. This remedy extinguishes the security provider’s legal and beneficial title to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company but not its obligation to pay any secured and unpaid sums. Foreclosure involves a time-consuming and costly court process and is not usually exercised in practice given its draconian nature.

For further details regarding the enforcement of security over Secured Shares in a Secured Company, please refer to our guide entitled “Enforcing security over shares in a Cayman Islands exempted company”.

Foreign law governed security document

Where the security document is governed by foreign law, the:

i. security document should comply with the requirements of its governing law to be valid and binding; and

ii. remedies available to a secured party are governed by the governing law and the terms of the security document.

5. Application of proceeds of enforcement

Subject to any provisions to the contrary in the security document, all amounts that accrue from the enforcement of the security document are applied in the following order of priority:

- firstly, in paying the costs incurred in enforcing the security document;

- secondly, in discharging the sums secured by the security document; and

- thirdly, in paying any balance due to the security provider.

6. Security deliverables

The terms of a well-drafted Cayman Islands law governed security document with respect to Secured Shares in a Secured Company and the principal finance document will usually require the security provider to deliver the following documents to the secured party to assist with an enforcement:

- any original share certificate(s) with respect to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company;

- an undated share transfer form with respect to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company;

- an undated resignation letter from each director of the Secured Company;

- a letter of authorization from each director of the Secured Company authorizing the secured party to date each undated letter of resignation upon the occurrence of a default under the security document;

- an irrevocable proxy with respect to the Secured Shares in the Secured Company in favor of the secured party;

- a letter of instruction to the Secured Company’s registered office service provider containing, among other things, directions to register a transfer of Secured Shares in the Secured Company upon the occurrence of a default under the security document;

- a letter of acknowledgement from the registered office service provider with respect to the instructions referenced in the letter of instruction;

- if the security provider is a Cayman Islands exempted company, a certified copy of its register of mortgages and charges showing the security created over the Secured Shares in the Secured Company (see further below);

- a certified copy of the Secured Company’s register of members annotated to show the security created over the Secured Shares in the Secured Company (if commercially agreed – see further below);

- if the security provider is a Cayman Islands exempted company, a copy of the board resolutions of its board of directors authorizing:

a. its entry into and execution of the security document; and

b. the updates to its register of mortgages and charges;

- a copy of the board resolutions of the Secured Company authorizing:

-

- its entry into and execution of the security document (if it is a party);

- its register of members to be annotated (if commercially agreed); and

- a transfer of Secured Shares in the Secured Company upon the occurrence of a default under the security document; and

xii. a special resolution passed by the Secured Company with respect to certain changes to its M&A, if required (see further below).

7. Security protection steps

Register of mortgages and charges of a Cayman Islands security provider

Pursuant to section 54 of the Act, if the security provider is a Cayman Islands company, it must record particulars of the security created over any Secured Shares in the Secured Company in its register of mortgages and charges. The register of mortgages and charges must include:

- a short description of the property mortgaged or charged;

- the amount of charge created; and

- the names of the mortgagees or persons entitled to such charge.

There is no statutory timeframe within which the register needs to be updated. However, a well-advised secured party will request that the register is updated promptly so that third parties that inspect it are on notice of the security.

Any variations and releases of charge should also be reflected in the register of mortgages and charges.

As there is no statutory regime for registering security interests under Cayman Islands law, the common law rules of priority continue to apply. In general terms, these rules specify that priority between competing security interests is determined by the dates on which the relevant security interests were created. It is important to note that inserting details of mortgages and charges in the register of mortgages and charges of a Cayman Islands company does not confer priority on a charge in respect of the relevant secured asset.

Register of members of the Secured Company

A Secured Company may annotate its register of members to include:

- a statement that security has been created over the Secured Shares;

- the name of the secured party; and

- the date on which the statement and the secured party’s name are entered in its register of members.

Although it is optional to annotate a Secured Company’s register of members with details of any security that has been created, this puts third parties that inspect the register on notice of the security. Therefore, a secured party usually insists on this.

M&A of the Secured Company

A secured party will usually request the Secured Company to make certain changes to its M&A to ensure, among other things, that there are no restrictions on the transfer of Secured Shares in the Secured Company which may impede enforcement action. Any changes to the Secured Company’s M&A must be made by passing special resolutions. Although such resolutions need to be filed with the Registrar of Companies of the Cayman Islands within 15 days of being passed, they take effect upon signing.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact:

Peter Vas

Partner

Loeb Smith Attorneys

Hong Kong

www.loebsmith.com

Introduction

As the regulatory requirements and cost burden increase for investment management entities in the Cayman Islands, many of our clients are looking for other offshore solutions. Under the Cayman Islands’ Securities Investment Business Act (2020 Revision) as amended, all Cayman entities carrying on securities investment business as investment managers and/or investment advisers (“SIBL Managers and/or Advisers”) are required to either (i) register with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (“CIMA”) as a Registered Person, or (ii) apply to CIMA for a licence in order to carry on such business. The vast majority of these SIBL Managers and/or Advisers opt for the more straightforward status of Registered Person which requires the applicant to, among other things, (i) have at least two (2) Directors, (ii) comply with continuing reporting obligations to CIMA, (iii) appoint AML officers and have a compliance manual, and (iv) pay the fee of approx. US$6,098 for first registration with CIMA and thereafter pay the same fee to CIMA on an annual basis for continued registration.

The impact of the Economic Substance Act on Cayman Investment Managers

The logistical challenges and economic costs of complying with the Economic Substance Act has also caused a substantial increase in the number of existing Cayman Islands’ Investment Managers (who exercise discretionary authority over the investments they manage) either winding down their affairs and de-registering from CIMA or restructuring their relationship with investment funds in order to deal with these challenges and control costs. It has also meant that clients looking to establish new funds in the Cayman Islands, which continue to be the premier offshore jurisdiction for establishing investment funds, are increasingly looking for new offshore options for establishing an investment management entity.

BVI Approved Manager regime

One attractive offshore option is establishing an “Approved Manager” in the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) under the Investment Business (Approved Managers) Regulations 2012 (As Amended) (the “Regulations”) and the Approved Investment Managers Guidelines. The BVI Approved Manager regime has less onerous regulatory requirements than the licensed regime in the BVI and is similar in a number of respects to the Registered Person regime in the Cayman Islands. However, there are some crucial differences.

Key features of the BVI Approved Manager regime

i. A BVI company or limited partnership can apply to the BVI Financial Services Commission (the “FSC”) for approval as an Investment Manager and if approved would become an “Approved Manager”.

ii. The application fee payable to the FSC is US$1,000 (significantly less than the application fee of circa US$6,098 payable for an Investment Manager with Registered Person status in the Cayman Islands).

iii. An application to the FSC must be submitted at least seven (7) days prior to the intended date for the commencement of relevant business and provided the applicant makes the submission to the FSC within this time period, the applicant may commence and carry on relevant business for a period of up to thirty (30) days from the date of submission of the application (such period being extendable for a further period of 30 days by the FSC). During this 30 day (or extended) period, the applicant will be deemed to have been approved under the Regulations if ultimately approved by the FSC.

iv. Significantly, an Approved Manager does not fall within the scope of the BVI economic substance law regime.

Significantly, an Approved Manager does not fall within the scope of the BVI economic substance law regime.

v. An Approved Manager has no capital adequacy or professional indemnity insurance requirements.

vi. Under the Approved Manager regime there is a US$400 million cap on assets under management for open-ended funds and a cap of US$1 billion of capital commitments for closed-ended funds. If these limits are exceeded, the Approved Manager must inform the FSC within seven (7) days. The funds it manages can be funds in the BVI or equivalent funds in another recognized jurisdiction (e.g. the Cayman Islands, China, Switzerland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States). If these limits are breached, then within three (3) months of the limit being breached, the Approved Manager is required to either (i) apply for a licence under Part I of the BVI Securities Investment Business Act, or (ii) the funds which the Approved Manager manages or advises must have decreased back below the limits otherwise it must immediately cease carrying on relevant business on the expiry of the three (3) months period.

vii. An Annual Return for the Approved Manager is required to be filed with the FSC to confirm the Approved Manager and its senior team remain in compliance with BVI regulations, along with details of the funds under management and any significant complaints received from investors.

viii. An Approved Manager is required within fourteen (14) days of the change of any information submitted to the FSC during the application process to notify the FSC in writing of the change, providing details of the change and a written declaration in the prescribed form as to whether or not the change complies with the requirements of the Regulations.

ix. Financial Statements – Annual financial statements must be submitted, however these are not required to be audited.

x. Directors – Approved Managers must retain at least two (2) directors (as is the case under the Registered Person regime in the Cayman Islands) and always have a licensed authorised representative in the BVI.

xi. Annual Fee – The Approved Manager is required to pay an annual fee of US$1,500 (significantly less than the annual registration fee of circa US$6,098 payable for an Investment Manager with Registered Person status in the Cayman Islands) to the FSC for renewal of its approval as an approved manager.

xii. Anti-Money Laundering Compliance – Unlike the position for Registered Persons in the Cayman Islands, the Approved Manager is exempt from the requirement to appoint a compliance officer. However an Approved Manager is required (i) to appoint a money laundering reporting officer (MLRO) and (ii) maintain policies and procedures with respect to client identification, record keeping, internal reporting and internal controls and communications, which meet the requirements set out in the BVI Anti-Money Laundering Regulations and the BVI Anti-Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Code of Practice.

For specific advice on the BVI Approved Manager regime, please contact your usual Loeb Smith attorney or any of:

E: elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

E: santiago.carvajal@loebsmith.com

Cayman Islands exempted companies (“Cayman Companies” and each a “Cayman Company”) are widely utilized in structuring cross-border finance transactions. One of the key reasons for this is that the Cayman Islands provides a flexible and well-tested regime for secured financing transactions that is attractive to borrowers and lenders alike. The process for creating security in the Cayman Islands is also straightforward and will not typically impact the timeframe of a proposed transaction.

In this brief guide, we address certain of the key Cayman Islands law points pertaining to the creation and protection of security by a Cayman Company over its assets. For details with respect to the creation of security over Cayman Islands shares, please refer to our separate guide entitled “Granting and protecting security over shares in a Cayman Islands exempted company”.

This guide does not consider the additional steps that may be necessary for the purposes of creating and protecting security over specific asset classes, such as Cayman Islands registered aircraft and ships, or land located in the Cayman Islands.

1. Creation of security

The Companies Act (as Revised) of the Cayman Islands (the “Act”) does not contain any provisions with respect to the creation of security over the assets of a Cayman Company. Therefore, the security should adhere to the following common law principles:

i. it must be in writing;

ii. the security document must signed by, or with the authority of, the Cayman Company; and

iii. the security document must clearly indicate the intention to create security over the relevant assets and the amount secured or how that amount is to be calculated.

Cayman Islands law recognizes various forms of security over assets, including legal mortgages, equitable mortgages, charges and assignments by way of security. The type of security interest that is created will depend on the type of asset to be secured.

2. Execution formalities and regulatory approvals

Cayman Islands law does not prescribe a particular mode of execution with respect to security over the assets of a Cayman Company and it is not necessary for such security to be certified, notarized or apostilled to make the security valid or enforceable from a Cayman Islands law perspective.

It is important to review the memorandum of association and articles of association of the Cayman Company to ensure compliance with any applicable signing formalities.

No regulatory approvals are necessary to create valid and enforceable security as a matter of Cayman Islands law in respect of security that is created over a Cayman Company’s assets.

3. Stamp duty and taxes

No stamp duty or taxes are payable with respect to the creation of security over the assets of a Cayman Company or upon any transfer thereof in an enforcement as a matter of Cayman Islands law so long as:

i. the security document and any ancillary documents thereunder are not executed or delivered in, brought into, or produced before a court of, the Cayman Islands; and/or

ii. the assets do not comprise land in the Cayman Islands, or shares in a subsidiary that has an interest in land in the Cayman Islands.

4. Governing law

Cayman Islands law permits security over the assets of a Cayman Company to be governed by Cayman Islands law or foreign law.

In cross-border finance transactions, it is relatively common for the governing law of a security document over the assets of a Cayman Company to be aligned with the governing law of the principal finance documents or the lex situs of the secured asset. One advantage of adopting a foreign governing law clause in a security document is that it may make available certain additional remedies (such as appropriation) which are not available under Cayman Islands law. Care should however be taken to ensure that there are no conflicts of law issues where a security document is governed by foreign law. English, Hong Kong and Singapore law are frequently adopted to govern security over the assets of a Cayman Company and no major conflicts of law issues are likely to arise.

Where the security document is governed by foreign law, the:

i. security document should comply with the requirements of its governing law to be valid and binding on the Cayman Company; and

ii. remedies available to a secured party are governed by the governing law and the terms of the security document.

5. Security deliverables

The Cayman Company will typically be required to deliver the following documents to the secured party under the terms of the relevant security document and/or the other finance documents:

i. a certified copy of its register of mortgages and charges showing the security created over the secured assets (see further below); and

ii. a copy of the board resolutions of its board of directors authorizing:

a. its entry into and execution of the security document; and

b. the updates to be made to its register of mortgages and charges.

6. Register of mortgages and charges

Pursuant to section 54 of the Act, a Cayman Company must record particulars of the security created over any of its assets in its register of mortgages and charges. The register of mortgages and charges must include:

i. a short description of the property mortgaged or charged;

ii. the amount of charge created; and

iii. the names of the mortgagees or persons entitled to such charge.

There is no statutory timeframe within which the register needs to be updated. However, a well-advised secured party will request that the register is updated promptly so that third parties that inspect it are on notice of the security.

Any variations and releases of charge should also be reflected in the register of mortgages and charges.

A copy of the register of mortgages and charges (including a blank register if no prior security has been granted) must be kept at the registered office of the Cayman Company and is a private record that is not open to inspection by the public. However, any creditor or member of the Cayman Company may inspect the register at all reasonable times.

If a Cayman Company does not comply with the aforementioned provisions, every director or officer who authorizes or knowingly and willfully permits such non-compliance is liable to a penalty. This does not invalidate the validity, enforceability or the admissibility in evidence of the charge, however.

As there is no statutory regime for registering security interests under Cayman Islands law, the common law rules of priority continue to apply. In general terms, these rules specify that priority between competing security interests is determined by the dates on which the relevant security interests were created. It is important to note that inserting details of mortgages and charges in the register of mortgages and charges of a Cayman Company does not confer priority on a charge in respect of the relevant secured asset.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact:

Peter Vas

Partner

Loeb Smith Attorneys

Hong Kong

T: +852 5225 4920

E: peter.vas@loebsmith.com

2020 saw an explosion of special purpose acquisition companies (“SPACs”) in the United States that was largely driven by favorable economic returns to SPAC IPO sponsors, liquidity and pricing certainty offered by SPACs to target companies and investors. The extended low-interest rate environment and the speed to market that SPACs offer compared to traditional IPOs has also played a significant role. Although an initial drop of SPAC activity characterized the second quarter of 2021 – due to the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s concerns regarding forward looking statements and the accounting treatment of warrants – 2021 looks set to be another record-breaking year for SPACs with around US$110 billion raised in capital as at 15 April 2021 .

Most SPAC IPOs have so far been arranged by US managers and take place on NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange. However, the tides are turning as Asian players are looking to enter this space and we have seen an increase in enquiries from Asia-based sponsors and investors with respect to SPAC IPOs and de-SPACs alike. The Singapore Exchange announced new rules on 2 September 2021 to enable SPACs to list on the Main Board of the Singapore Exchange which, coupled with the influx of seasoned managers with proven track records and the increasing volume of high-profile SPAC transactions, has arguably lent sufficient credibility to the structure as a reputable investment vehicle to trigger widespread interest in Asia.

In this article, we provide an overview of SPACs and their advantages, consider the future of SPAC IPOs in Asia and the role that the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”) and the Cayman Islands play in facilitating them.

1. What is a SPAC?

A SPAC is a shell company which is specifically incorporated by its initial sponsors for the purpose of raising capital through an IPO for use in the acquisition of a target company. The SPAC does not have any operating assets or operations and is commonly a BVI or a Cayman Islands company.

2. What is a de-SPAC?

The acquisition by a SPAC of a target company is usually referred to as a de-SPAC. Most SPACs typically have between 18 and 24 months in which to identify a target company and complete an acquisition. If an acquisition is not completed within that timeframe, the proceeds of the IPO need to be returned to the investors. Investors can also redeem their shares prior to the de-SPAC if they do not want to participate in the acquisition.

3. Why are SPACs generally attractive to sponsors?

The SPAC sponsor typically receives shares for nominal consideration at the time the SPAC is incorporated. These shares normally represent around 20% of the SPAC equity following the SPAC IPO, which predominantly serves as a “finder’s fee” for identifying a target company, conducting due diligence and closing the de-SPAC transaction. Coupled with the current extended low-interest rate environment, these highly favorable economic returns have continued to attract sponsors to invest in SPACs.

4. What are some of the key features of SPACs?

SPACs have various distinctive features as follows:

i. SPAC trust account: The proceeds of a SPAC IPO cannot be used for any purpose other than to fund the relevant de-SPAC transaction or to redeem the shares sold to the investors in the IPO. The funds that are raised from the IPO are held in an interest-bearing trust account.

ii. IPO units and classes of shares: Each unit that is sold to a public investor in a SPAC IPO typically comprises a class A share and a fraction of a warrant to purchase a class A share in the future. The units typically become separable 52 days after the IPO, at which point the component securities can trade separately. In contrast, class B shares are purchased by the sponsor at the formation of the SPAC which typically convert into class A shares at the time of the de-SPAC transaction on a 1:1 basis. Unlike the class A shares, the class B shares are usually subject to transfer restrictions and are not subject to redemption. The class B shareholders also typically have the right to appoint and remove directors prior to the closing of the de-SPAC transaction.

iii. No acquisition target at the time of the IPO. A SPAC may (and commonly does) identify certain geographic areas and/or specific industries in which it will pursue a target company in order to de-SPAC in its IPO prospectus. That being said, a SPAC cannot identify its acquisition target prior to the closing of the IPO and there are typically disclosures regarding this in the relevant prospectus.

iv. Structuring of a de-SPAC: A typical de-SPAC is usually structured as a merger transaction, but the specific method that is used to acquire a target company will depend on where it is incorporated, tax considerations, whether the target company is also a listed entity and the methods of merger that are available in the applicable jurisdictions to complete the de-SPAC transaction. Typically, the target company will merge with a wholly-owned subsidiary of the SPAC and the shareholders of the target company will receive new shares in the SPAC in consideration for their shares in the target company. Both the BVI and the Cayman Islands have straightforward and well-tested statutory merger regimes which are conductive to de-SPAC transactions and familiar to corporate lawyers.

5. What are some of the key advantages of SPACs compared to more traditional structures used by private equity and venture capital firms for investment?

SPACs have arguably unlocked various advantages over more traditional structures used by private equity firms for investment. For example, SPAC investors benefit from the liquidity of publicly traded securities and have limited risk exposure as they are entitled to a return of their funds held in the trust account if the SPAC fails to complete an acquisition or the investor does not want to participate in one. In addition, there is typically no cash compensation paid to the management team of the SPAC pending completion of the de-SPAC transaction and their reward will depend on the success of the acquisition.

6. Are SPAC IPOs speedier to complete than traditional IPOs?

Yes, a SPAC IPO will be speedier to bring to market because it will not be necessary to complete due diligence on an existing operating company. As a direct consequence of this, some SPACs can complete an IPO within 8-12 weeks versus 12 months (or more) for a traditional IPO.

7. Are SPACs in Asia going to become popular?

Asia-based sponsors and investors have demonstrated a keen interest in SPAC IPOs on US stock exchanges, particularly in the technology sector. In response to this, the Singapore Exchange announced new rules on 2 September 2021 to enable SPACs to list on the Main Board of the Singapore Exchange. This is a welcome development that may also revive Singapore’s lagging IPO market which saw only 3 IPOs in the first half of 2021 . Other stock exchanges in Asia, such as in Hong Kong, are also considering lifting their long-standing prohibitions on raising funds for unspecified purposes. Whilst Asia’s more conservative approach to SPACs is unlikely to match the level of deal-flow or capital raising seen in the US in the short or medium term, Asia’s financial markets are reliant on a steady-stream of IPOs to remain competitive so we foresee that key financial centers in Asia will develop a suitable regulatory framework for SPACs. It should also be noted that a number of SPACs are currently exploring de-SPAC opportunities in China and South Asia where an abundance of private equity backed companies with promising growth prospects are located.

8. Considering that SPAC fundraising in Asia may be more limited, what options are available to a SPAC to mitigate the liquidity risk associated with shareholder redemptions and to fund the post-closing operations of the combined entity?

Many SPACs issue new shares to institutional investors in a PIPE – which stands for private investment in public equity – that closes concurrently with the de-SPAC transaction in order to raise additional funding. These PIPEs are important in ensuring the completion of the de-SPAC transaction in the event there are significant redemptions and they also provide third-party validation of the terms and valuation of the acquisition.

The sponsor or institutional investors may also enter into forward purchase arrangements with the SPAC to commit to purchase new shares of the SPAC concurrently with closing of the de-SPAC transaction.

9. Why do Cayman Islands SPACs continue to be more popular than BVI SPACs?

Most SPACs pursuing US targets continue to be incorporated in Delaware, although the BVI and the Cayman Islands also remain popular. We expect the popularity of BVI and Cayman Islands incorporated SPACs to increase as SPAC activity picks up in Asia because BVI and Cayman Islands companies are widely used across the region and familiar to stock exchanges, regulators and other relevant market participants.

Cayman Islands SPACs are currently more popular than BVI SPACs, probably because the Cayman Islands continues to be the jurisdiction of choice for listed companies and private equity funds. That being said, BVI companies may confer certain advantages in the context of SPAC transactions. For example, the shareholder approval thresholds in a de-SPAC transaction for a statutory merger are typically lower in the BVI than the Cayman Islands.

10. What specific features of BVI and Cayman Islands law make these jurisdictions attractive for SPACs?

There are various features of BVI and Cayman Islands law which make these jurisdictions attractive for SPACs, including:

i. Unlimited objects. BVI and Cayman Islands companies may have unlimited objects and purposes which is important because SPACs will, in our experience, describe their target in terms that are as broad as possible in their IPO prospectus.

ii. Flexibility. There is significant flexibility in tailoring the articles of association of the relevant SPAC to accommodate the issuance of warrants and different classes of shares, as well as the incorporation of defensive takeover tactics.

iii. Capital maintenance. The rules on capital maintenance (where applicable) are flexible, permitting distributions and share redemptions from a wide range of sources subject only to the usual solvency tests.

iv. No takeover code. There is no takeover code or legislation that is specifically applicable to listed companies (with the exception of the Cayman Islands Code on Takeovers and Mergers that is only applicable to companies whose securities are listed on the Cayman Islands Stock Exchange).

v. Foreign private issuer. BVI and Cayman Islands companies that are listed on a US stock exchange may be able to qualify as a “foreign private issuer”, thereby taking advantage of reduced disclosure and reporting requirements.

vi. Statutory merger regime. Both the BVI and the Cayman Islands have well-established and straightforward statutory merger regimes which are conductive to de-SPAC transactions.

vii. Secured creditor friendly. The BVI and the Cayman Islands are widely recognized as creditor friendly jurisdictions, which is helpful in the context of facilitating a financing that a SPAC may require to consummate a de-SPAC transaction. The BVI also has a straightforward system of registering security interests which is attractive to secured creditors.

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. For specific advice, please contact:

Peter Vas

Partner

Loeb Smith Attorneys

Hong Kong

T: +852 5225 4920

E: peter.vas@loebsmith.com

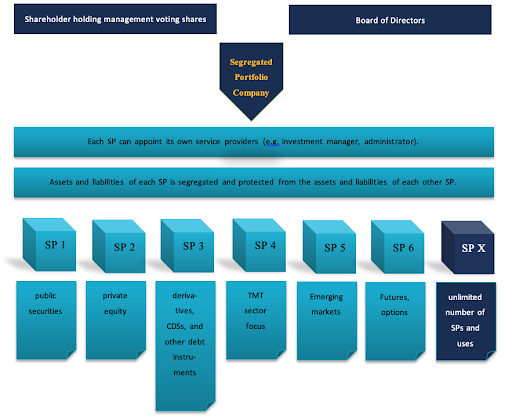

Once registered under the Cayman Islands Companies Act (As Revised), a segregated portfolio company (“SPC”) can operate segregated portfolios (“SPs”) with the benefit of statutory segregation of assets and liabilities between portfolios. The principal advantage of an SPC over a standard exempted company is to protect the assets of one portfolio from the liabilities of other portfolios.

The benefits of SPCs

- The SPC corporate structure is frequently used for multi-class hedge funds, umbrella funds and master-feeder structures owing to the various benefits of the SPC structure.

SPC provides ability to set up a statutory “ring-fence” to protect against cross liability issues relating to the assets and liabilities of the various SPs within a SPC. - The annual Government fees for an SP is 50% less than the annual Government fees for an exempted company.

- The SPC is a Cayman corporate structure, like a standard exempted company, where there are no residency restrictions on Directors or Shareholders.

- There are no exchange control restrictions.

- There are no Cayman taxes on the SPC or its shareholders, among other benefits.

- As shown in figure 1 below, the SPC structure is used increasingly as an investment platform on which investors can use different SPs to hold varying asset classes (e.g. real estate, intellectual property, stocks and shares, and distressed assets) and have their investments managed separately from other investments held by other SPs on the same SPC platform.

What are the features of a Segregated Portfolio Company?

- Under Cayman Companies Act, an SPC is an exempted company which has been registered as a segregated portfolio company. It has full capacity to undertake any object or purpose subject to any restrictions imposed on the SPC in its Memorandum of Association (“Memorandum”). The Memorandum of an SPC usually gives the SPC full capacity to pursue very broad objects. For example, the Memorandum of an SPC typically has a clause such as this (emphasis added):

“The objects for which the Company is established are unrestricted and the Company shall have full power and authority to carry out any object not prohibited by the Companies Act…or any other law of the Cayman Islands.” - Cayman Companies Act permits an SPC to create one or more SPs in order to segregate the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within one SP from the assets and liabilities of the SPC held within another SP of the SPC.

- The general assets and general liabilities of the SPC (i.e. assets and liabilities which cannot be properly attributed to a particular SP) are held within a separate general account rather than in any of the SP accounts.

- The Companies Act requires an SPC to make a distinction between “segregated portfolio assets” (which are assets of the SPC that have been designated or allocated for the account of a particular SP of an SPC) and general assets (which are assets of the SPC that have not been designated or allocated for the account of any particular SP of the SPC). Each SP should have, as appropriate, its own bank account, brokerage account, and other accounts to hold its assets to avoid co-mingling with the assets of other SPs.

- How are SP assets comprised? – The assets of an SP comprise (a) assets representing the share capital and reserves (“reserves” include profits, retained earnings, capital reserves and share premiums) attributable to the SP; and (b) all other assets attributable to or held within the SP (e.g. bonds, stocks, real estate, IP). Shares of the SPC are permitted to be issued in respect of a particular SP, the proceeds from the issue of such shares are included in the assets of that SP and the shares may carry the right to distributions from that SP. The proceeds of the issue of shares which are not segregated portfolio shares shall be included in the SPC’s general assets.

- The Companies Act also requires an SPC to make a distinction between “segregated portfolio liabilities” (which are liabilities of the SPC that have been designated or allocated for the account of a particular SP of the SPC) and general liabilities (which are liabilities of the SPC that have not been designated or allocated for the account of any particular SP of the SPC).

- It is the duty of the Directors of the SPC to establish and maintain (or cause to be established and maintained) procedures:

- to segregate, and keep segregated, portfolio assets separate and separately identifiable from general assets;

- to segregate, and keep segregated, portfolio assets of each SP separate and separately identifiable from segregated portfolio assets of any other SP; and

- to ensure that assets and liabilities are not transferred between SPs or between an SP and the general assets otherwise than at full value.

- Who controls the SPC? – The SPC will have a Board of Directors. In addition, each SP can have its own segregated portfolio directorate or investment or management committee which effectively controls and manages the operations of the relevant SP. The segregated portfolio directorate, investment or management committee would obtain its powers through powers delegated to it by the Board of Directors of the SPC.

- Contracting on behalf of an SP – Whilst the SPC is a company and therefore a corporate entity with separate legal personality, an SP does not have separate legal personality. Accordingly, the Companies Act requires that when contracting on behalf of a particular SP, it should be made clear which SP the SPC is contracting on behalf. Each SP can have its own investment manager, trading advisor, and other service providers but it should be made clear in the agreements which SP of the SPC has engaged them for their services. For example, if ABC Investments SPC enters into a trading advisory agreement to engage a trading advisor for segregated portfolio A1, the SPC should make it clear in the agreement that it is acting as: “ABC Investments SPC acting solely for and on behalf of segregated portfolio A1”. The trading agreement should also be executed as: “ABC Investments SPC acting solely for and on behalf of segregated portfolio A1”.

- Who can bind an SPC or an SP? – The SPC has the capacity to enter transactions “acting solely for and on behalf” of one or more SPs as stated above, the SPC must identify the relevant SP and state that it is: “acting solely for and on behalf of” the particular named SP. It is the Board of Directors of the SPC (or other person to whom the Directors have delegated authority, e.g. the investment manager) that will be able to bind the SPC and the relevant SP in respect of which the SPC is acting.

- Directors at SP level? – There will not be a Board of Directors as such at the SP level because it is not a separate corporate entity. However, often the Board of Directors of the SPC in a fund structure will delegate management of the SPC and/or the SPs to an investment manager or to an investment or management committee.

- Can assets be transferred between SPs? – The Companies Act requires the Directors of the SPC to ensure that assets and liabilities are not transferred between SPs otherwise than at full value.

- Rights of creditors – The Companies Act requires that segregated portfolio assets must only be available and used to meet liabilities to the creditors of the SPC who are creditors in respect of that SP and who shall thereby be entitled to have recourse to the segregated portfolio assets attributable to that SP for such purposes. Segregated portfolio assets should not be available or used to meet liabilities to, and shall be absolutely protected from, the creditors of the SPC who are not creditors in respect of that SP, and who accordingly shall not be entitled to have recourse to the segregated portfolio assets attributable to that SP.

Accordingly, a creditor will only have recourse to assets from SPs with which it has contracted and creditors will have no recourse to the assets of other SPs of the SPC which are protected under the Companies Act. This statutory protection afforded under the Companies Act to the assets of each SP is one of the key feature and benefit of the SPC structure.

xiv. Transfers to General Assets to meet expenses – Sometimes the Articles of Association of the SPC empowers the Directors of the SPC to transfer segregated portfolio assets to the general assets of the SPC (and, if more than one SP is in existence, pro rata in proportion to the net asset value of each SP or in such other proportion as the Directors determine) in order to discharge the following liabilities: government registration fees, annual return fees, professional fees, service provider fees, taxes, fines and penalties and any other liabilities or a recurring nature necessarily incurred in maintaining the continued existence and good standing of the SPC.

(xv) Segregation of Liabilities and rights of third parties – The liabilities to a person arising from a matter imposed on, or attributable to, a particular SP, only entitle that person to have recourse to that particular SP in the first instance and then to the general assets of the SPC, unless the Articles of Association of the SPC prohibits payments from the general assets of the SPC, in which case there is no recourse to the general assets.

This Briefing Note is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice or a legal opinion. It deals in broad terms only and is intended to merely pro-vide a brief overview and general guidance only. For more specific advice on the Cayman Islands segregated portfolio companies, please refer to your usual Loeb Smith contact or:

Gary Smith

Partner Loeb Smith Attorneys

Cayman Islands

This article was first published in Asia Business Law Journal which can be accessed here: https://law.asia/side-letter-cayman-subscription-financing/

Subscription facilities dominated the Asian fund finance industry in 2020. However, as a result of widespread concerns about liquidity and an uncertain macroeconomic outlook, it has become more important than ever for a lender to undertake proper due diligence on an investment fund prior to providing new financing.

This article examines the most important issues pertaining to side letters to the limited partnership agreement (LPA) of a Cayman Islands exempted limited partnership (ELP), which are relevant to a lender looking to advance a subscription facility. ELPs remain the vehicle of choice for subscription financing transactions in Asia. The following are examples of side letter provisions that a lender will typically scrutinise:

Limitations on the incurrence of debt and collateral support

Side letters should not prohibit, restrict or impose limitations on the incurrence of debt, the giving of a guarantee and/or the granting of security, if that cuts across the terms of the proposed subscription financing. To the extent that an investor wishes to include such provisions in a side letter, carve-outs should be included to accommodate the financing transaction.

Excuse rights

An investor may wish to be excused from honouring a drawdown notice with respect to immoral investments, or in geographies or industries to which the investor is politically sensitive. These types of rights are relatively common, and are typically accommodated by most lenders. However, a lender will usually seek to exclude such an excused investor from the relevant ELP’s borrowing base, and may insist on a default event if the excused commitments exceed a specified threshold. This is typically negotiated, as excuse rights are investor-specific and generally unrelated to the creditworthiness of an investor.

Confidentiality restrictions

Any restrictions that prevent the disclosure of investor information are likely to lead the lender to exclude the applicable investor from the relevant ELP’s borrowing base because a lender may not be able to enforce its security if it does not have details of the investor, or be in a position to satisfactorily complete legally required “know your customer” checks. A compromise may be to agree to disclosure on a default, or to reassure investors that the lender has robust confidentiality safeguards.

Limitations of direct obligations to a lender

A lender will usually take issue with a provision which provides that an investor only owes direct obligations to the fund parties, as this may undermine its ability to enforce any security. If an investor is concerned about granting broad powers or rights to a non-fund party, such as a lender, a compromise may be to make clear that any limitations are not intended to prohibit or limit a lender from taking enforcement action on a default.

Limitations on documents from an investor

An investor may wish to receive side letter comfort that it will not have to sign or provide any documentation to a lender in connection with a subscription financing. Provided that the LPA includes customary representations and covenants that prospective financiers have the benefit of, this may prove sufficient from a lender’s perspective. The LPA could impose an obligation on the relevant ELP to use its best endeavours to avoid any requests to investors.

Sovereign immunity

A lender may exclude an investor that has the benefit of immunity from the relevant ELP’s borrowing base, but that will ultimately depend on the specific credit analysis that is undertaken. As a minimum, an investor that has such benefit will usually be asked to confirm that its obligations to the ELP are not subject to such immunity.

Transfers to an affiliate

An investor may wish to have the option to transfer its interest in the relevant ELP to an affiliate specified by it. A lender may seek to exclude such an affiliate from the relevant ELP’s borrowing base from a credit perspective. A compromise may be to permit transfers to affiliates, as long as this does not breach the ELP’s borrowing base.

Most favoured nation (MFN) provisions

As a final point, it is important to note that any adverse consequences for a lender of side letter terms may be multiplied if MFN provisions are included. A cost-friendly solution may be to include a carve-out with respect to provisions that detrimentally impact a lender in a subscription financing.

Peter Vas

Partner Loeb Smith Attorneys

Hong Kong

T: +852 5225 4920

E. peter.vas@loebsmith.com

Questions relating to Cayman Islands and BVI Law

Questions relating to Cayman Islands’ Law

What is the authorization or licensing process for Cayman Islands funds? What are the key requirements that apply to managers of investment funds in the Cayman Islands?

The vast majority of open-ended investment funds will qualify as mutual funds under the Mutual Funds Law (As Revised), which requires mutual funds to be licensed or regulated as such. Closed-ended funds (i.e., investment funds that issue investment interests which are not redeemable at the option of the investor of record), which fall within the scope of the Private Funds Law (As Revised), are also required to register with, and consequently become regulated by, the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA).

The authorization process for an open-ended investment fund will depend on the regulatory category it chooses to register under (e.g., a licensed fund under section 4(1)(a) of the Mutual Funds Law, an administered fund under section 4(1)(b) of the Mutual Funds Law, a registered fund under section 4(3) of the Mutual Funds Law, or a limited investor fund under section 4(4) of the Mutual Funds Law). For closed- ended investment funds, the authorization process requires the investment fund to:

submit an application for registration to CIMA within 21 days after its acceptance of capital commitments from investors for the purposes of investments;

file prescribed details in respect of the private fund with CIMA;

pay a prescribed annual registration fee to CIMA in respect of the private fund;

comply with any conditions of its registration imposed by CIMA; and

comply with the provisions of the Private Funds Law.

A Cayman Islands domiciled fund manager will have to either apply to CIMA for a licence to undertake business as such under the Securities Investment Business Law (As Revised) or apply to CIMA to be registered as a Registered Person.

An overseas fund manager can provide services to a Cayman Islands investment fund and there is no requirement for the overseas fund manager to be licensed by or registered with CIMA unless that fund manager establishes itself in the Cayman Islands. Operators of mutual funds registered with CIMA, such as directors, are subject to registration or licensing requirements under the Director Registration and Licensing Law and are required to register with CIMA.

For specific advice, please contact any of:

E: gary.smith@loebsmith.com

E: vivian.huang@loebsmith.com

E: yun.sheng@loebsmith.com

E: elizabeth.kenny@loebsmith.com

E: santiago.carvajal@loebsmith.com

T: +1 345 749 7591

Suite 329, 10 Market Street

Camana Bay, Grand Cayman KY1-9006 Cayman Islands

The risk of back-dating Cayman Islands law governed documents

If the parties to an agreement governed by Cayman Islands law would like the agreement to take effect from a date earlier than the date upon which the agreement was signed and entered into, the parties should expressly state in the document that it is intended to be effective from a date earlier than the date on which the parties entered into the agreement. It should be made clear in the document that notwithstanding it being entered into on the date of execution by the parties, it is to take effect from a date in the past.

Stating that the contract or agreement will be effective from an earlier “effective date” will, however, only be effective as between or among the parties to the contract or agreement. It will not affect those parties’ obligations under the terms of the contract or agreement with regard to third parties who are not parties to the agreement. The obligations to third parties will almost invariably be based on the date that the contract or agreement was fully executed subject to any applicable special circumstances.

It is worth noting that whilst parties signing a contract or agreement may expressly state that the contract or agreement is effective from a date in the past, the parties should not “back-date” the date of execution (for example, sign the contract or agreement today and but insert an earlier date as the date of the document, thereby making it seem as if it was signed on some earlier date). This could run the risk of civil and/or criminal sanctions in a number of jurisdictions (for example, depending on, among other things, the nature and subject matter of the contract or agreement, false accounting or false statements by directors, or even conspiracy to defraud).

On 25 May 2020 the Cayman Islands government passed The Virtual Asset (Service Providers) Law, 2020 (“VASP Law”), which provides a legislative framework for the conduct of virtual assets business in the Cayman Islands and for the registration and licensing of persons providing virtual asset services. The VASP Law is intended to place the Cayman Islands with a cutting edge, robust framework which is in alignment with global regulatory standards, protect consumers and meet the requirements of the Financial Action Task Force recommendations in respect of virtual assets. In this two part series (this being Part 2) we look at the new VASP Law and its requirements with respect to licensing. Part 1 looked at the requirements with respect to registration.

1. WHAT IS A VIRTUAL ASSET?

The VASP Law defines a “virtual asset” as “a digital representation of value that can be digitally traded or transferred and can be used for payment or investment purposes but does not include a digital representation of fiat currencies”.

The VASP Law makes a distinction between a “virtual asset” as defined above which will be regulated and a “virtual service token” which is defined as “a digital representation of value which is not transferrable or exchangeable with a third party at any time and includes digital tokens whose sole function is to provide access to an application or service or to provide a service or function directly to its owner.”

The distinction is meant to deal with the usual question as to whether or not a digital token or coin is a security or a utility token. Virtual service tokens will be treated as utility tokens and therefore will fall outside the registration regime and the licensing regime under the VASP Law.1

2. WHAT ARE VIRTUAL ASSET SERVICES?

The VASP Law states that “Virtual asset service” means the issuance of virtual assets or the business of providing one or more of the following services or operations for or on behalf of a natural or legal person or legal arrangement:

- exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies;

- exchange between one or more other forms of convertible virtual assets;

- transfer of virtual assets;

- virtual asset custody service; or

- participation in and provision of financial services related to a virtual asset issuance or the sale of a virtual asset.

3. WHO IS A VIRTUAL ASSET SERVICE PROVIDER?

A person is a “virtual asset service provider” (“VASP”) under the VASP Law, if it is (1) a company, or a general partnership, or a limited partnership, or a limited liability company, or a foreign company registered in the Cayman Islands, and (2) provides a virtual asset service as a business or in the course of business in or from within the Cayman Islands and is registered or licensed in accordance with the VASP Law or is an existing licensee that is granted a waiver under the VASP Law.

A natural person cannot carry on or purport to carry on a virtual asset service as a business or in the course of business in or from within the Cayman Islands.

The VASP Law requires a VASP to either register with Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (“CIMA”) or be licensed by CIMA. Whether the VASP will have to register or be licensed will be dependent on the activity carried out by the VASP. However, broadly speaking, in the case of the provision of virtual asset custodial services or the operation of a virtual asset trading platform, the VASP is required to have a virtual asset service licence. It appears that in most cases where the VASP is carrying on business as a VASP but is not providing virtual asset custodial services or the operation of a virtual asset trading platform, registration with CIMA is required.

4. CIMA CONSIDERATIONS: LICENCE OR REGISTER

In determining whether to grant a virtual asset licence, a sandbox licence, register an applicant as a “registered person” or to waive a requirement to licence or register under the VASP Law, CIMA will take into account the following:

- size, scope and complexity of the virtual asset service, underlying technology, method of delivery of the service and virtual asset utilised;

- knowledge, expertise and experience of the applicant;

- the AML procedures that the applicant has in place;

- internal safeguards and data protection systems being utilised by the applicant;

- the similarity of the virtual asset service to securities investment business or any other regulated activity under any of the other Cayman Islands regulatory laws;

- the risks involved;

- whether the virtual asset service business involves the offering of virtual asset custodial services or the operation of a virtual asset trading platform;

- the net worth, capital reserves and financial stability of the applicant;

- the likelihood that the service will promote innovation, competition and benefits to consumers; and

- the applicant’s senior officers, trustees and beneficial owners are fit and proper persons.

5. VIRTUAL ASSET SERVICE LICENCE

A person who wishes to (i) provide virtual asset custody services (i.e. the business of safekeeping or administration of virtual assets) or (ii) to operate a virtual asset trading platforms (“VATP”) or is at the commencement of the VASP Law already doing so, should apply for a virtual asset service licence. For the purposes of the VASP Law, a VATP does not include a platform that only provides a forum where buyers and sellers post bids and offers and a forum where the parties trade in a separate platform or in a peer-to-peer manner.

- CIMA criteria – In order to determine whether to approve an application for a licence, CIMA will consider the matters set out in section 4 above, whether approval of the application is against the public interest and if the applicant has (i) personnel with the necessary skills, knowledge and experience (ii) facilities, books, records and accounting systems, and (iii) adequate capital and cybersecurity measures, as CIMA considers appropriate having regard to the size, scope and complexity of the business. When CIMA has granted a licence, it will publish notification in the Cayman Islands Gazette.

- CIMA regulatory requirements – CIMA may impose such regulatory requirements on a virtual asset service licensee as it considers necessary, including further restriction or prohibitions on the use of technology or practices which CIMA deems may disrupt or prejudice the functions of CIMA, the interests of the public and the financial services in the Cayman Islands.

- Event-driven notifications – In addition to an annual renewal fee which is due by 15th January each year, a licensee is required to notify CIMA within 15 days of any changes made to the information in the application form submitted to CIMA.

- Annual Audit obligations for Licensees – A licensee is required to have its accounts audited annually and submit such accounts to CIMA within 6 months of financial year end. CIMA may grant an exemption to this requirement if CIMA determines the requirement to be unnecessary or prohibitive given the size, scope and complexity of the economic activity and the availability of auditing services to the virtual asset service.

6. REQUIREMENTS: VIRTUAL ASSET CUSTODY SERVICES

A licensee that provides virtual asset custody services must:

- maintain best technology practices relating to virtual assets held in custody;

- not encumber or cause any virtual asset to be encumbered, unless specifically agreed to by the beneficial owners of the virtual assets;

- ensure that all proceeds relating to virtual assets held in custody shall accrue for the benefit of the owner, unless otherwise agreed in writing;

- take such steps as may be necessary to safeguard the virtual assets held;

- have adequate safeguards against theft and loss; and

- enter into a custodial arrangement with the owner of a virtual asset, which includes the prescribed details set out in the VASP Law (i.e. in relation to the manner in which the virtual assets are to be held, the transactions the custodian is permitted to engage in, disclosures relating to the risks and fees etc.).

CIMA may also impose requirements on a licensee that provides virtual asset custody services, including (i) net worth requirements, (ii) reporting requirements, (iii) disclosures to clients concerning the transparency of operations, (iv) requirements for the safekeeping of client assets (including the segregated of assets, insurance requirements and cybersecurity measures), and (v) any other requirement CIMA determines is in the best interest of the beneficial owners of the assets held by the licensee.

7. REQUIREMENTS: VIRTUAL ASSET TRADING PLATFORMS

- CIMA requirements – CIMA may impose requirements on a licensee that operates a VATP where CIMA deems it necessary, including: (i) the type of client it may market its services to, (ii) the types of virtual assets that may and may not be traded on the VATP, (iii) the clearing and settlement process for transactions between buyers and sellers of virtual assets, and (iv) net worth and reporting requirements.

- Due diligence requirement – A licensee operating a VATP is required to carry out reasonable due diligence procedures on virtual assets and their issuers listed on the VATP.

- Securities investment business – A licensee who is operating a VATP must apply to CIMA, in the prescribed form, for approval prior to engaging in securities investment business2 (as defined under the Cayman Islands Securities Investment Business Law (“SIBL”)) which relates to virtual assets. In determining an application by a VATP, CIMA will take into account whether the VATP lists or facilitates the issuance of securities which are virtual assets in accordance with SIBL and whether any additional supervision is required under SIBL.

- Prohibitions on a licensee – A licensee that operates a VATP shall not:

-

- provide financing to clients for the purchase of virtual assets, unless disclosures are made to client regarding the terms and risk of the financing;

- engage in trading or market making behavior for its own account which could be detrimental to the interests of its clients, unless these activities are necessary for the operation of the VATP and these activities have been disclosed to clients of the VATP;

- allow a virtual asset to be traded on the VATP unless it has assured itself that the virtual asset is not presented in a deceiving manner or in a manner that is meant to defraud;

- allow a client to purchase or trade in virtual assets unless the licensee has assured itself the client is aware of the risks of purchasing, holding or trading the virtual asset and has provided disclosures in a form that the client can understand; and

- provide fiat currency to fiat currency exchange services to users of the VATP.

8. SANDBOX LICENCE

A “sandbox licence” is a temporary licence granted for a period of up to 1 year for a person providing a virtual asset service that represents an (i) innovative use of technology or (ii) uses an innovative method of delivery that requires supervision and oversight not offered by an existing licence or registration.

- CIMA supervision – CIMA shall assess, monitor, supervise the innovative service, technology or method of delivery of a sandbox licensee with a view to ensuring that the service, technology or delivery (i) complies with the core principles of a sandbox licence, as set out in the VASP Law, (ii) improves the provision of financial services within the Cayman Islands, (iii) complies with global standards and best AML practices, (iv) facilitates the adoption of new financial services practices and technologies within the Cayman Islands, and (v) best practices and guidance are developed for the virtual asset service sector.

- Direction by CIMA – CIMA has the discretion to require a person applying to be a registered person or a virtual asset service licensee to apply instead for a sandbox licence.

- CIMA powers – CIMA may take any action necessary where it is of the opinion that the action is necessary for the protection of clients or potential clients and is in the interest of the public, may extend the duration of the sandbox licence, amend any restrictions or revoke it.